Element Zero, a groundbreaking green-iron startup, promised to help save the planet—until the founders’ former boss called in the dogs, and the lawyers. With billions at stake, the green gloves are off.

Bart Kolodziejczyk is almost home for Christmas 2020 having spent almost six months travelling a COVID-19-ravaged world with his boss, iron-ore magnate Andrew Forrest, when he fires off an email to Forrest.

The Fortescue chairman, Forrest, had taken his entourage to almost 50 countries, meeting world leaders, thought leaders and start-ups, hunting sources of renewable energy to fuel the hydrogen revolution that Dr Forrest was intent on driving; seeking inspiration; seeking redemption from the 2 million tonnes of greenhouse gasses his company generates each year.

Dr Kolodziejczyk – Fortescue chief scientist – copies senior Fortescue employee, Michael Masterman, into the email sent on December 22, 2020 about progress towards using green hydrogen to make green steel … but also, he’s working on a patent application based on his “initial work done a couple of years ago,” [he’d started at Fortescue 21 months earlier] in which he says he has created what might be construed as a suite of “green” metals using electrical currents rather than a blast furnace.

“… I have managed to produce iron from iron oxides, copper from copper complexes, and nickel from nickel oxides,” Kolodziejczyk writes. “I would like Michael and you to be listed as co-inventors. We wouldn’t be doing this work if not for your push. Are you OK with being on that patent?”

But Kolodziejczyk never does put in that patent application. Ten months after the email, he resigns from Fortescue and, 13 months after that, he begins his own green-iron start-up, Element Zero, with his former Fortescue boss, Masterman, and former colleague Dr Bjorn Winther-Jensen as co-founders.

They raise US$10 million from one of the world’s leading impact venture funds, get some good press about saving the world, and then, in May 2024, make headlines again.

It turns out Forrest’s Fortescue had private investigators following them and Kolodziejczyk’s family, and had got a court order to search their houses and business for evidence that they’d taken Fortescue’s trade secrets.

Fortescue sues, seeking ownership of their green-iron patent.

The race to save the planet has suddenly become the race to save the IP.

Green fields and blue skies

Michael Masterman, now CEO of Element Zero, and Andrew Forrest go way back. After stints with the Hawke/Keating government and at consultants McKinsey, Masterman came to work for Forrest at his first company, Anaconda Nickel, in the late 90s where he says he was tasked with financing the $1.2 billion Murrin Murrin nickel/cobalt mine. He left Anaconda in May 2001, 12 months before Forrest who departed in May 2002 after the company almost collapsed.

In 2003, when Forrest bought some iron tenements in the Pilbara and launched Fortescue Metals, he reached out to Masterman again. “He asked me to help with the initial capital optimisation, the port, the railway, and the first mine.”

Masterman left – with a little equity – when Fortescue was soaring on the stockmarket to $10 a share. He was enticed back in 2010 as it was clawing its way out of its GFC $2-a-share hole. “Andrew asked me to come back on board … As part of that, I was involved in what led to the development of the Iron Bridge project, and in particular, completed a $1.2 billion transaction where Formosa Plastics came in as an investor.”

A spokesperson for Fortescue said Masterman’s version of his career with Fortescue was incorrect but did not say in which aspect. Masterman dismisses Fortescue’s claims, saying his work with Fortescue is easy to verify and publicly available.

Masterman left Fortescue again, but in 2020 Forrest called once more, says Masterman, and asked him to chair Squadron Energy, the renewables company owned by Forrest and his now estranged wife, Nicola.

Masterman agreed, and while Squadron was busy growing from zero assets to being Australia’s largest renewable energy operator, Forrest asked Masterman to now help with Fortescue Future Industries [FFI] the business tasked with getting Fortescue to carbon neutrality and, more generally, with just speeding up the global energy transition.

Masterman admired Forrest’s ability to bring big ideas to fruition with small teams – and fast. And the big idea behind FFI was to save the world from climate catastrophe by making hydrogen power viable.

“In February 2020, Fortescue Future Industries was literally seven people in a room,” recalls Masterman, who came on as chief financial officer. Now, merged back in with Fortescue Metals and rebadge simply Fortescue, it has 1,500 people in 32 countries.

In August 2020, with the world in the grip of COVID-19, Forrest took his team on the world tour looking for clean hydrogen opportunities. That was where Masterman and Kolodziejczyk got to know each other well.

“I don’t mind challenges but this is out of proportion.”

Element Zero co-founder Bjorn Winther-Jensen

They entourage visited most of the ‘Stans’. The Taliban attempted to assassinate Afghanistan’s vice president Amrullah Saleh while they were there, killing 10 with a roadside bomb. Forrest caught the coronavirus from a Russian interpreter in Uzbekistan and wound up in a Swiss hospital. “Things like that kind of made us question whether we’d even get back to Australia,” Kolodziejczyk tells Forbes Australia. He had a newborn son at home. The stakes were high.

But Forrest bounced back. And hydrogen was hot. Interest rates were next to zero so there was the prospect of borrowing large amounts to build the enormous renewable energy projects needed to power a hydrogen revolution. Hydrogen is not a source of energy. It’s a store of energy. To be viable – and green – it needs cheap renewable power.

World leaders had empty diaries. “We had exceptional access,” says Masterman.

The more they travelled and talked, the more other opportunities came into focus – the largest of which was green iron and steel. Steel production is said to be responsible for 7-9% of global greenhouse gas emissions.

Whoever cuts that number changes the world.

A stretch

When they got home in January and endured two weeks of “iso”, Kolodziejczyk, originally from Poland, whose expertise in hydrogen had been honed in Iceland then at Melbourne’s Monash University, joined FFI’s R&D team which formed a group to develop an electrochemical pathway to take iron ore and convert it to metallic iron with minimal carbon emissions.

The traditional way to turn iron ore to metal has been to use large amounts of coal in a blast furnace such that, for every tonne of steel produced, two tonnes of carbon dioxide are created.

He wrote that email about having produced metals through the electrolysis process “a couple” of years earlier – he now maintains it was in 2012-13 when he was at Monash University.

Kolodziejczyk set about recruiting his former PhD supervisor from Monash, Dr Winther-Jensen who understood electrochemistry better than anyone he knew. Winther-Jensen, originally from Denmark, was living between Thailand and Japan in semi-retirement. He had his name on multiple patents involving electrolysis – that is, the type of process Kolodziejczyk was proposing in his email to convert ore to metal by passing a current through it.

Winther-Jensen wanted to move his family back to Australia and so took the Fortescue job, starting in February 2021.

“Having been through the journey with Universal Hydrogen, I had some healthy scepticism as to whether that green-iron approach was ever going to work.”

Peter Barrett of co-founder Playground Global

Forrest had imposed “stretch targets” on the team. Whatever tech they came up with, they needed to be testing it in the Pilbara by June 30 that year, just four months away. Kolodziejczyk and Winther-Jensen wrote emails trying to figure out how they were going to hit such a tight target.

Winther-Jensen was overwhelmed by it. “I cannot commit to produce any meaningful ‘something’ by the end of June 2021,’ he writes in an email later tendered to court. “I don’t mind challenges but this is out of proportion.”

He says the fastest way to reach the target would be to ditch electrolysis and use hydrogen in a blast furnace at up to 1,500C, but he knew nothing about such processes. “These processes are well outside my expertise and a more appropriate person should be appointed for pursuing such path,” he writes.

And they never discussed the electrolysis method again via email or any other traceable platform.

Four months later, Kolodziejczyk resigned from FFI [in October 2021] and was told not to work out his notice.

Winther-Jensen followed him out 14 days later, in November, citing “significant stress and anxiety” after just seven months on the ground in Perth. “I felt that the volume of work and the deadlines that I was required to meet were incredibly difficult and in some cases impossible,” he says in an affidavit.

Winther-Jensen was also told to leave immediately he finalised some work. Both men downloaded documents which, Fortescue would claim, was confidential IP. The two scientists say they did not download any key documents, just routine materials to finish the work Fortescue required of them.

Kolodziejczyk got a job with Boston Consulting. Winther-Jensen retired, and after leaving Australia before returning to Perth, he began tinkering with some electrolysis ideas in his Scarborough garage from March 2022.

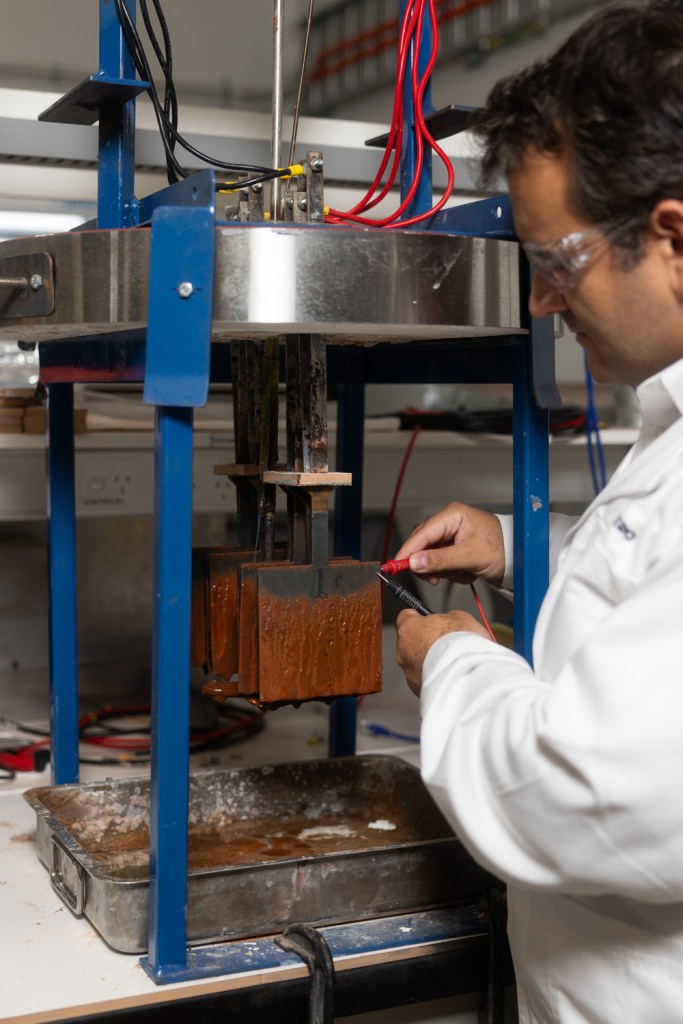

“This was driven by curiosity and to have a small retirement ‘project’ exploring the footsteps of [chemists] Humphry Davy’s and Michael Faraday’s work from 1807 on electrodeposition from molten hydroxides. I worked with nickel initially but then branched into iron in about July 2022,” Winther-Jensen says in his affidavit.

Not long after, Masterman also left the Forrest camp. “There were some changes in management in 2022, that made it sensible for me to step back,” he tells Forbes Australia. He began looking for climate-tech start-ups to invest in.

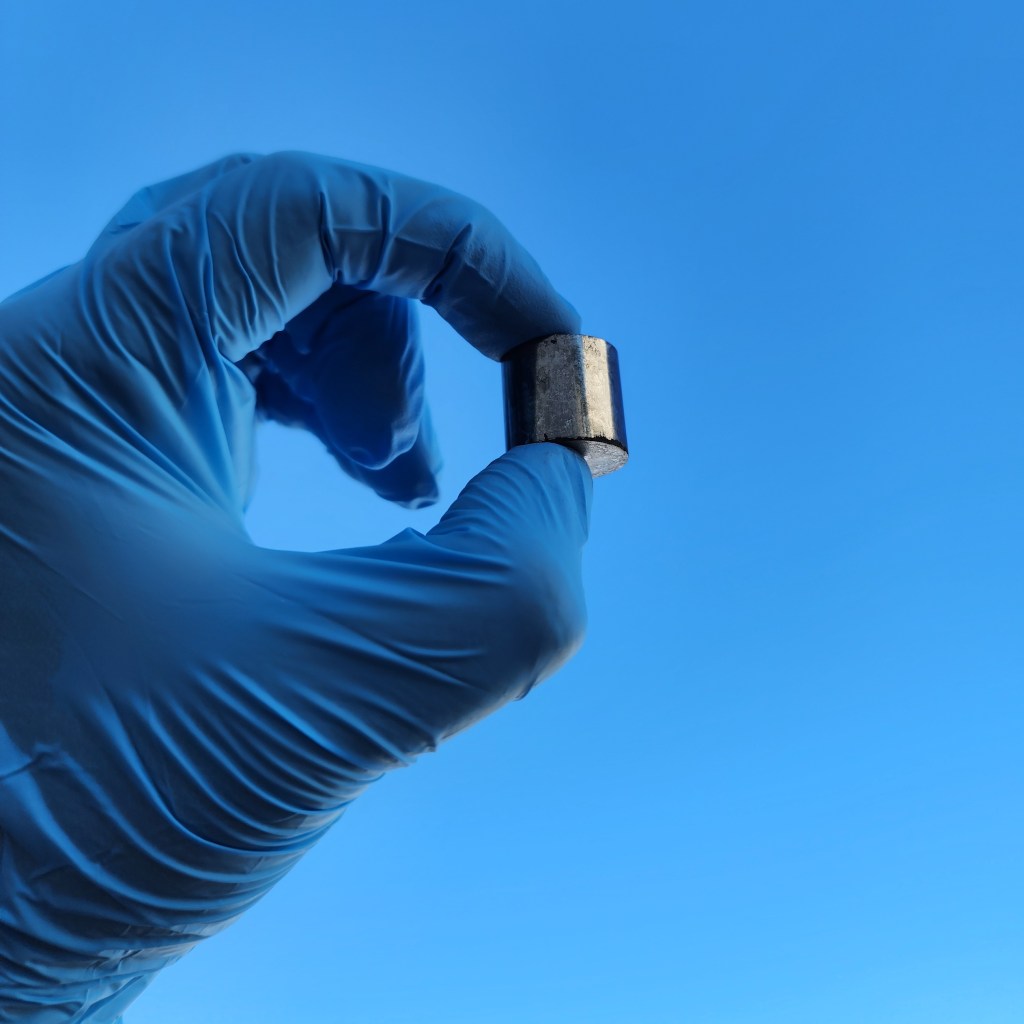

Kolodziejczyk and Winther-Jensen had stayed in touch. Kolodziejczyk helped the Dane source iron ore for his experiments. No one had previously tried dissolving iron ore in the alkaline solution that the two scientists came up with, they say, long after leaving Fortescue. When the iron ore went into the beaker it dissolved into a solution. And when they turned the electricity on, metallic iron plated onto the cathode.

Eureka!

So long as the power was renewable, they had cracked zero emissions iron.

Billionaires’ Playground

Excited, Kolodziejczyk reached out to Masterman. They met up for coffee in Melbourne. Masterman jumped on board over coming months, investing $3.8 million, and they formed Element Zero in December 2022, just over a year since the two scientists had left FFI.

Element Zero maintained good relations with Fortescue through 2023, securing ore from the mining giant for its experiments and signing non-disclosure agreements so they could share their work.

Masterman reached out to the renowned Australian expat investor, Peter Barrett, whose Silicon Valley venture fund, Playground Global, has an unparalleled record of picking unicorns.

Barrett had met Kolodziejczyk and Masterman when Barrett had written a term sheet for Fortescue Future Industries to invest in Universal Hydrogen, a much-hyped start up attempting to make hydrogen-powered aeroplanes.

[Universal Hydrogen collapsed in July 2024, having burnt through $150 million of investor money, a significant chunk of which was Forrest’s.]

Barrett and Playground were scouring the globe looking for a green-steel project to back. “We couldn’t find anything that I felt really scaled,” says Barrett. “Typically, when you hear people talking about green iron today, they’re talking about using hydrogen instead of coal to turn the iron ore into iron. And the problem with that is that that only works on 3% of the world’s ores, and hydrogen is insanely expensive to produce, and having been through the journey with Universal Hydrogen, I had some healthy scepticism as to whether that green-iron approach was ever going to work.”

Barrett could see Element Zero’s approach solved many problems. He loved that it worked on “most of the interesting things that we dig out of the ground in Australia [copper, nickel, silicon], and it has real implications for decarbonising and scaling up the critical-mineral supply chain that doesn’t require blast furnaces with Australian coal in China”.

“Over a couple of years, I realised that Michael was a character who thought at scale, and had done huge project financing in mining,” says Barrett. “And Bart was a unique talent, a real polymath.”

“If you guys want to start a company, I want to write you a cheque,” he recalls telling them. Playground put in 90% of Element Zero’s US$10 million seed raise in August 2023.

Trade secrets

A week after Element Zero won a Bloomberg New Energy Finance Award, in April 2024, Fortescue had a patent lawyer spend more than a week combing 3,000 documents seeking evidence they’d used FFI property, according to documents later tended to court. The manager of minerals, research & developments at who’d arrived after Kolodziejczyk left, Dr Anand Bhatt, was given the job of reading the correspondence.

He found an email from January 2021 where Kolodziejczyk states that Fortescue’s iron ore will be “dissolved in a unique electrolyte” and that the “selection of electrolyte, electrode material, and other materials used in the process is proprietary, and at this point, Fortescue’s trade secret”.

Bhatt says in an affidavit that, having read that, he expected to then find other documents pertaining to experiments and patents involving this unique electrolyte, but there were none. “I am therefore concerned that Dr Kolodziejczyk and Dr Winther-Jensen have intentionally not uploaded onto the Fortescue IT system and/or taken and/or deleted the above work product during or prior to ceasing their employment with Fortescue.”

Kolodziejczyk rejects the notion that this absence of evidence is evidence of theft. For much of the time in question, he said, he was on Forrest’s world tour or scrambling to hit hard targets on the hydrogen furnace, plus working on another of Forrest’s newfound interests – zero-carbon cement. [Kolodziejczyk produced samples of “zero carbon cement” made from iron ore byproduct “gangue”, in late August 2021.]

Fortescue’s investigations led to 19 days of surveillance by private investigators on the Element Zero team and their families. Kolodziejczyk’s wife confronted a guy after she’d dropped her son off at daycare, sure that he was following her. He drove off as she chased him. Neighbours contacted them about a car with tinted windows and NSW plates parked outside their Melbourne home for three days.

Fortescue lawyers convinced a judge there was a risk that material might be destroyed if they simply subpoenaed documents. So court orders were given to search premises, seize documents and go through computers.

Kolodziejczyk was the only one in the office as Fortescue’s team of lawyers raided, staying for the entire12 hours as they also searched his home. They did not search Masterman’s home.

Forrest distanced himself from such methods, telling the media he’d been unaware of them. A week later, he announced Fortescue was pulling back from much its hydrogen ambition, sacking 700 workers, but announcing it had switched its focus to green iron.

Chilling

Element Zero needs to raise $300 million to build its stage-1 commercial plant and $2 billion to build a much larger stage-2 plant.

Masterman admits it’s going to be easier to raise more money when the court case is behind them. He maintains that they’ve got enough cash to avoid being litigated out of existence. Their principal backer, Playground, is, afterall, a US$1.2 billion fund.

Playground’s Barrett remains on side. “It’s chillingly effective if any innovation in Australia is subject to well-funded companies crushing it at will without merit … but I think there’s a clear path to them getting through that and realizing their ambition and we’re super supportive of what they’re doing and looking forward to growing that into a big company.”

Form guide

Ever since his boss, Andrew Forrest, handed Chinese Premier Li Qiang a vial of Fortescue’s very first batch of green iron in Perth last June, Fortescue Metals CEO Dino Otranto has found doors opening in China.

“When you’ve got a second-in-charge [Li Qiang] who’s a bit of a tech head – he helped bring Tesla to China – he gets it, right? He was so interested and fascinated in this [green iron] work,” Otranto tells Forbes Australia. “My conversations since that time with the steel mills in China, they’re like, ‘Is Fortescue really seriously doing this stuff?’”

Yes, they really seriously are, Otranto tells them.

All this comes on top of two deals worth US$3.2 billion last year to decarbonise Fortescue’s mining equipment and eliminate “terrestrial emissions” by 2030.

To crack green iron, Otranto is running two teams of researchers competing for the prize. One is working on an electrolysis process like Element Zero’s, but at a lower temperature and with a different way of reducing the ore to a fluid. “We have a huge plant here [in Perth]. We call it lab scale, but it takes up a whole building which is now making significant volumes with this electrolytic-route,” Otranto says.

The other team is more advanced, building a $50 million test plant at the Green Energy Hub at Christmas Creek, Port Hedland. And while it’s long been thought hydrogen furnaces didn’t work for Australian iron ore, Fortescue claims to have solved it.

“We’ve been able, through a conventional furnace technology, to use [iron ore] fines … and burn it with hydrogen for two purposes: using the heat of hydrogen, but also using the reducing chemical factors of hydrogen, to create a liquid metal from Australian-based fines iron ore,” says Otranto.

Forrest has set a target of opening the Christmas Creek plant by the end of 2025, when it is forecast to produce 1,500 tonnes of iron per annum.

Forrest told the Chinese Premier that Fortescue wants to, eventually, convert all 200 million tonnes of its annual iron ore production into 100 million tonnes of green iron.

“We have plans for a 1-million tonne and a 10-million tonne project which are in concept stage,” says Otranto. “Then that just scales up. They’re unitised. We want to drive the capex of these installations down and we feel that’s the best way to do it. And then as the market develops and the cost continues to go down, you’d extend those units in the Pilbara.”

And which technology does Otranto think will win out?

“I don’t have a favourite. So which child do you love more? It’s literally that analogy. They used to be one team, but I separated them into two. I said, ‘Now you’re both racing, boys.’ My job is to clear away all the roadblocks and let them go. If both work, even better, because some areas you may want to have more hydrogen-based, or if you’re in a hydro-rich area like Canada, you may choose the electrochemical route.”

Otranto declined to comment on Element Zero or the court case.

Green metallic iron is currently worth 8-to-10 times more than iron ore, per tonne. Fortescue says in court documents that it expects green iron will sell for $200/tonne more than standard iron if a $100/tonne carbon tax was in place. So there is an enormous profit increase to be had if it can get this technology to work.

How it works

Element Zero uses a patented solution – a eutectic – which, like salt on icy roads, changes a substance’s melting point. Iron ore “fines” go in and, in 30 minutes to two hours, they dissolve to a solution of iron oxides. An electric current then splits the oxygen from the iron. The oxygen goes to the atmosphere and 96%-to-98% pure iron plates the cathode, which is then scraped clean.

The energy cost of producing a tonne of Element Zero iron will be $140 a tonne, compared to $135 to produce 92% pure pig iron in a standard blast furnace, says Masterman. But green electricity will power it, rather than coal.

Element Zero has not signed any offtake agreements, but has signed NDAs with major steel producers such as Hyundai Steel, Nippon Steel, Mitsubishi, Japan’s largest, and the world’s largest, Baowu Group, in China, Masterman says.

Masterman had a meeting with the chairman of Japan’s second largest steel maker, JFE Steel, recently, he says. “They estimate for every tonne of green iron we send them, they can save 75% of their carbon emissions. Outside the power-generation companies, they would be the largest carbon emitter in Japan.”

Element Zero has a 22-hectace site in Port Hedland, near power lines bringing in electricity from the BP-led Renewable Energy Hub, which has plans for 26 gigawatts of wind and solar power across the Pilbara.

Element Zero has plans drawn up for two “commercial-scale step ups”. Stage 1 would cost about $300 million and produce 255,000 tonnes of green iron a year. “That’s around $250 million of revenue,” says Masterman. “Then the stage-2 plant takes us up to about 2.6 million tonnes a year of green iron.”

Such a plant needs about $2 billion of investment to build, but would reap a cash flow of about $1.2 billion, he says.