Palmer Luckey sold his first business to Facebook for US$2 billion when he was 21. At 30, he’s bringing his defence disruptor to Australia to build submarines and much more.

Palmer Luckey loves Australia. The proud American patriot, famous for Hawaiian shirts and libertarian views, also has a great fondness for Australia’s bureaucrats.

“Try spending some time in the United States, and you’ll understand,” he says, responding to a raised Aussie eyebrow.

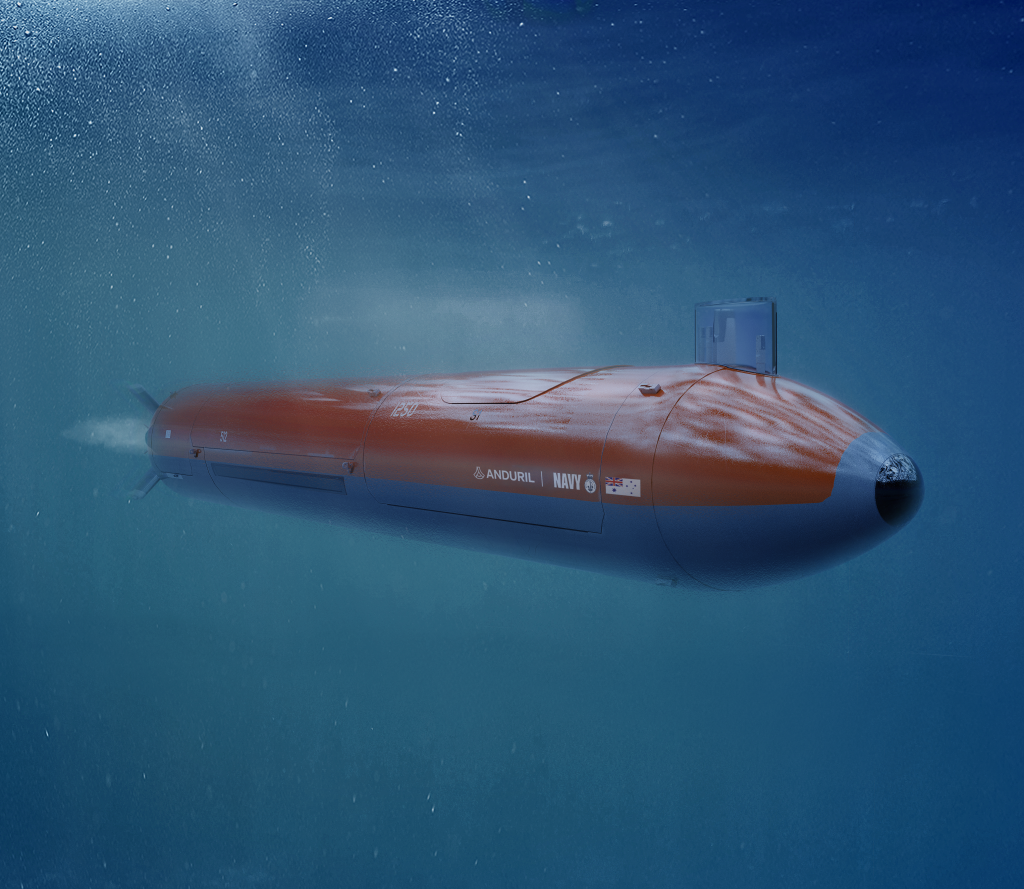

Luckey is one of only four self-made US-dollar billionaires under 30, according to Forbes. He has good reason to like Australian public servants. Five months after the initial cold call, his startup, Anduril, had inked a $140-million deal with the Australian government to build three bus-sized robotic submarines – “Ghost Sharks” – in Australia, with the understanding the Royal Australian Navy would take plenty more – at a much lower price – if the subs prove themselves.

There are other reasons for his fondness for Australian bureaucrats. “One is that we found good people in Australia,” he says. “In the United States, we have a huge defence apparatus. We have many competing internal political machinations that mean that a program that makes sense is not necessarily one that can get through the bureaucracy.”

And Australia is more cognisant of the benefits of a company like Anduril moving in, says Luckey.

“When we say we’re going to bring $70 million of our own money and build a team of hundreds of people on just this initial program – that’s something where the government says, ‘We’re paying attention.’”

Palmer Luckey

It’s not like Anduril has been ignored in the US.

Six years after its founding, it was valued at US$8.48 billion last December when it raised US$1.48 billion in its sixth funding round, bringing total capital injections to US$2.2 billion. It is reportedly taking in more than US$150 million in annual revenue.

The “additional things” Anduril is bringing to Australia include the manufacture of counter-drone systems and perhaps maritime surveillance systems. But their presence has, they say, prompted a battery manufacturer to move here, and they are helping their Australian suppliers raise capital to boost production to meet their needs. And it all started with a difficult kid tinkering in his dad’s garage.

IRON MAN

The only reason Luckey was home-schooled was that he was “not good at recognizing authority”. His sisters went to regular schools, he says. The educational burden mainly fell to his mother at their Long Beach California home, “but it takes both (parents) to manage someone like me when I’m young,” he says, dressed in kangaroo-paw Hawaiian shirt and loafers, flanked by his CEO and two flaks.

The deal was that if he got good test scores, he could use his time however he wanted. “I would sometimes get way ahead on things, and then I’d spend an entire month deep diving into something I was interested in – like virtual reality. I was also interested in solid-state and gas laser systems. I built a lot of high-powered lasers. I was interested in high-voltage stuff, so I built a Tesla coil, built some multi-stage electromagnetic accelerators – coil guns.”

But he wasn’t interested in making things that go bang because he felt explosives had no ‘low-hanging fruit.’ “It was clear that nobody was going to be pushing the limits in that stuff,” he says, “but in laser systems and virtual reality, there was still room for improvements.”

Luckey had finished high school at 15 and then attended community college. He transferred to the University of California at 17 and started a business, building VR headsets, Oculus, two years later. He then dropped out of university. Aged 21, he sold Oculus to Facebook for US$2 billion, of which Forbes estimated his cut to be US$700 million.

Luckey stayed on as a Facebook executive, but during the 2016 US presidential election campaign, he caused anguish with Silicon Valley colleagues by donating US$10,000 for a billboard of Hillary Clinton saying, “Too big to jail.”

Perhaps a larger headache was that he was being sued by a Texas VR headset manufacturer, ZeniMax, claiming he stole their trade secrets. A Dallas jury found in 2017 that he had not stolen their secrets in creating his Rift VR headset, but had breached a non-disclosure agreement and awarded US$500 million damages against him, Facebook and others. An appeal judge in 2018 threw out all claims against Luckey and halved the damages against Facebook to US$250 million.

Luckey was sacked by Facebook a month after the 2017 judgment. He maintains it was because of the donation. Facebook denied the claim but has not specified why he left.

“Facebook decided that instead of paying me tens of millions of dollars a year, they were going to pay me zero dollars a year, and I needed to move on.”

Palmer Luckey

“The relationship had soured, so I wasn’t surprised when it happened. I started Oculus in my garage, and it’s unthinkable that something you created from nothing can go on without you. At the same time, I’d been talking to some people about how to solve national security problems that I saw in the US. I’d already started trying to find companies in national security to invest in. When I was fired, I called up a few people – Trae Stephens, Brian Schimpf, Joe Chen, and Matt Grimm. ‘Hey, we need to start this company we’ve been talking about.’”

The “national security problems” he perceived were that A: Defense tended to order things off the drawing board on a cost-plus basis, so everything they touched was slow and expensive; and B: Silicon Valley was so frightened of alienating China that it would not work on defence projects. As a result, the country’s best and brightest were working on algorithms to drive traffic to twerking teenagers and not to defend the West’s implicit freedom to shake your backside at a camera.

“The problem was that they [tech companies] wanted to get into China to sell products there. And then many of them also manufacture in China. Apple has 95% of its manufacturing dependent on China, so it can’t do anything to upset China because it would destroy its entire business overnight.”

Luckey says things have started to change, with his old employer now actively lobbying against TikTok.

“They realised they were being strung along the whole time and would never be allowed into China – it was just an elaborate ruse the whole time.”

Palmer Luckey

But in 2017, on day one of the company they called Anduril, (It shares its name with a sword from the book Lord of the Rings in which the Elven word translates as “flame of the west”) when Luckey and his co-founders were sitting around a whiteboard figuring out what Anduril would look like and what it would build, heightened international tensions were not so obvious. The newly-elected President Trump was, however, being bellicose about China and Mexico.

Three of them had come from the defence and security focussed AI data-crunching company, Palantir, founded in 2003 by libertarian techy Peter Thiele.

The vision was to be cheaper and faster than the competition by conceiving and building products with their own money, rather than go through lengthy bureaucratic procurement processes.

Founder Matt Grimm recalls they had ideas for drone swarms, counter-drone systems, and robotic fighter jets. “Palmer had a crazy idea for a next-generation aircraft carrier that’s more like a floating city, not a ship. Not all of his ideas are good!”

Luckey is showing me a desert demonstration of the Altius 600M Loitering Munitiion, an Anduril drone that shoots out of a tube, can fly for a long time until it finds a target, then, with human permission, slam itself and its warhead into that target. I tell him he reminds me of the Tony Stark character in the movie Iron Man, in which the opening scene is a billionaire defence entrepreneur demonstrating a new system in the desert.

He points out his pauper status when he started Oculus, “but no, I liked the first Iron Man [which came out in 2008 when he was 16]. I loved when it showed Tony Stark soddering [soldering]. It was so refreshing to see a movie representing someone not just doing the magical thing where they tell the computer to do it all.” I point out that they have the same business model.

“It’s also the business model that every non-defence company uses,” he says.

“It’s rare to have an industry where you get paid to work on something from where it’s just an idea through to where it works – hopefully – and where taxpayers must keep funding it for years before there is anything usable. “

Palmer Luckey

“When we started Anduril, we knew we wanted to be the world’s next major defence prime [contractor]. We wanted to change how the DOD [US Department of Defense] did business. We wanted to build things that DOD desperately needed, that the existing defence companies were not very good at building, that we knew we could build with people from the technology industry.”

Helpfully, the DOD publishes a list of its priorities and right near the top are artificial intelligence and autonomy.

That first day around the whiteboard, they came up with the name, the logo and what they would build. The first thing they knew they needed was an “AI sensor fusion platform” – essentially an AI brain that would sit behind everything else they did. They called it Lattice. They wanted Lattice to be able to take data from thousands of sensors – from radar, vision systems and signals intelligence – react to that data and communicate it to humans.

“We were confident that we didn’t need to be the best AI company in the world. We just had to take the same level of AI expertise that existed in the self-driving car industry and apply that to military problems, and that would be lightyears ahead of anything the DOD had.”

Palmer Luckey

And beyond the military problems to be solved was a political one. President Trump needed to build a wall on the Mexican border. Within a few months, Anduril had convinced US Customs & Border Patrol to try out Anduril’s first proof of concept: AI sentry towers to detect people and vehicles crossing the border. In just over a year from founding, they were testing three automated observation towers on the Texas border – hooked into VR headsets. It caught 55 people crossing illegally in its first 12 days. In 2020, the agency awarded Anduril a $250-million contract to deploy 200 towers. Anduril was also developing a range of drones, and in 2022 won a US$1-billion contract to take charge of U.S. Special Operations Command’s drone defences.

The big fish will be the Pentagon’s integration of its surveillance and weapons systems into one platform, allowing a unified view of the battlefield remotely while resisting hacking and jamming. Anduril and others – including Palantir – are reportedly in the running.

THE NAVY’S HOLE

David Goodrich had for the last decade been negotiating defence contracts – from Super Hornets to the $52-billion French submarines – on behalf of the Australian government through his consultancy, Silver Spirit Partners. He explains that the last contract he negotiated for Defence was the $115-million second tranche of the Loyal Wingman (now known as Ghost Bat) drone contract with Boeing.

“I was sitting across the table from Dr Shane Arnott (Boeing’s Australian-born director of autonomous air systems), who was the program manager and visionary of Loyal Wingman. We were negotiating that second tranche of funding, then Shane left Boeing and popped up at Anduril.” Arnott had become Anduril’s senior vice president of engineering.

Arnott contacted Goodrich, explained Anduril’s mission and asked him to come on board. Goodrich was all in. He became Anduril Australia’s employee number one.

One of his first tasks, in November 2021, was to talk to the Royal Australian Navy. It was two months after the Morrison government had backed out of the contract for the French Attack-class submarines. The nuclear-powered replacements – costing up to $368 billion – would not be delivered until the 2040s. The Navy had a hole to be filled.

In February 2022, Anduril purchased Dive Technologies, a Boston-based pioneer in the world of autonomous underwater vehicles which made a range of small robotic subs.

Goodrich wanted to know what the Navy wanted. And could Anduril help? The RAN was already looking at two Australian-made autonomous subs, the 8-metre-long Speartooth being developed by C2 Robotics in Melbourne, and the 12-metre SeaWolf by Trusted Autonomous Systems out of Brisbane.

What the navy was interested in, though, was something larger.

Just 152 days after that first phone call, Goodrich signed a contract with the RAN and the Defence Science and Technology Group for Anduril to deliver three robotic, unmanned subs the size of a bus. Anduril would design and build them in Australia – in just three years. And if they proved any good, the contract stipulated that Anduril had to be ready to go into large-scale production immediately. The federal government and Anduril would each put in $70 million.

Despite the shortage of tech workers at the time, recruiting was easy, Goodrich says. Engineers want to do meaningful things instead of optimizing search engine results. “Many people think that protecting our freedom is a high-value order of their life … And we don’t recruit exclusively from one industry. We have folks from Tesla, SpaceX, Amazon, and Google. Many of them are Australians who used to work in the US and now have a reason to come home and work on some challenging, interesting stuff.”

And in terms of recruiting power, there was Luckey himself. Trae Stephens, an Anduril co-founder and partner at Peter Thiel’s Founders Fund, told Forbes in 2022 that Luckey’s chaotic creativity was infectious. “Smart people, especially engineers, want to be around Palmer because he’s electric. He is, when channeled appropriately, unstoppable.”

Anduril co-founder and chief operating officer Matt Grimm was given the job of “appropriately channelling” Luckey in Australia. He moved Downunder in 2022 to oversee the Ghost Shark project.

Goodrich stresses that Ghost Shark is “being designed in Australia, by Australians for the Australian Defence Department and for export”.

Luckey chimes in: “Think battery packs, energy management systems, the propulsion system itself, the propellers, the buoyancy control systems, the payload, signals sensing – all being built in Australia.”

Grimm stresses that Australia already can supply most of what is needed to build a submarine, but not hundreds of submarines. “So we’re looking at either Anduril just injecting capital into (existing Australian businesses) or leveraging future orders to enable private financing. We go to a supplier who can make X volume today and say, ‘Hey, we need you to make 3X in three years. What will it take to get there? We figure out a capital structure where we can tap into our network of investors. We’re pretty good at raising the money.”

GOING UNDERGROUND

The Anduril engineers conceived of a sub that wasn’t entirely waterproof. All the individual components would be “hydro proofed”, but flooded spaces would be between them. It’s much easier to waterproof a fridge than a bus, and that’s one of the innovations that’s made it possible to make the Ghost Shark cheaply, says Luckey. And he should know. “I own a 50-man submarine that’s very similar in size to Ghost Shark. But building something like that is much more expensive than doing it the way we’re doing it.”

Luckey says he uses his sub to “just have fun”, but he can relate to the RAN’s experience of conventional submarines. “You want to know what I do with it? I just spend money on it. It’s in overhaul right now. It won’t be diving again for months.”

Anduril will bring the manufacture of other weapons to Australia, says Luckey. The first will be counter-drone systems – drones that shoot down other drones. Anduril is also considering bringing a version of its Mexican-border sentry product to northern Australia, with different sensors, radars and cameras suited to maritime work.

Not all the manufacturing would be done in Australia, Luckey says, but whatever “makes sense” to make in Australia would be made. “Things like the surveillance towers, the battery packs, the solar power systems that run it – those things are going to be native Australian technology.

“It’s not just about knocking stuff out of the sky. It’s about jamming, hijacking communications lines, and detecting where the operator is. It’s a broad range of capabilities.”

Palmer Luckey

Only half the company’s products are publicly known, Palmer Luckey says. “There’s half dozen that already exist and are being sold that we can’t talk about, and there’s another half dozen that are up here (he points to his head).”

Does he have any teasers about what’s up there?

“When people talk about ‘all domains’ (of warfare), they typically mean surface, subsurface, land, air, space and cyberspace,” he says. “Nobody’s talking about the underground world as a domain. During the Cold War, the US and USSR both posited the idea of the subterranean, like a submarine that travelled underground using a nuclear-powered drilling system to drill around like a mole. But it’s never been practical because people are very hard to protect in this system, and building systems that are very large and dig underground are typically slow and expensive.

“AI and modern technology will turn the underground domain into a war-fighting domain just like all the others. Everyone acts like it doesn’t exist, but as soon as it becomes practical, it’s going to be a warfighting zone.”

“That’s Tony Stark signing off,” Goodrich says.