From deathbed promise to cancer breakthrough: Why big pharma is watching this Aussie biotech in Phase-2 trials.

Dr Jennifer MacDiarmid and Dr Himanshu Brahmbhatt are both working on animal vaccines for the CSIRO in the late 1990s when one of their best lab technicians starts coughing blood at the bench.

Rushed to hospital, the 40-year-old Kin San Lee is diagnosed with terminal lung cancer. Over coming days, Brahmbhatt and MacDiarmid sit with him, their minds churning with death-bed thoughts, wondering what it’s all about.

At one point, Lee points at them, Dr Brahmbhatt recalls more than a quarter century later. “And he says, ‘If anybody can do something about cancer, you can. So go and do it!’ The next day he was dead and both of us were seriously shocked.”

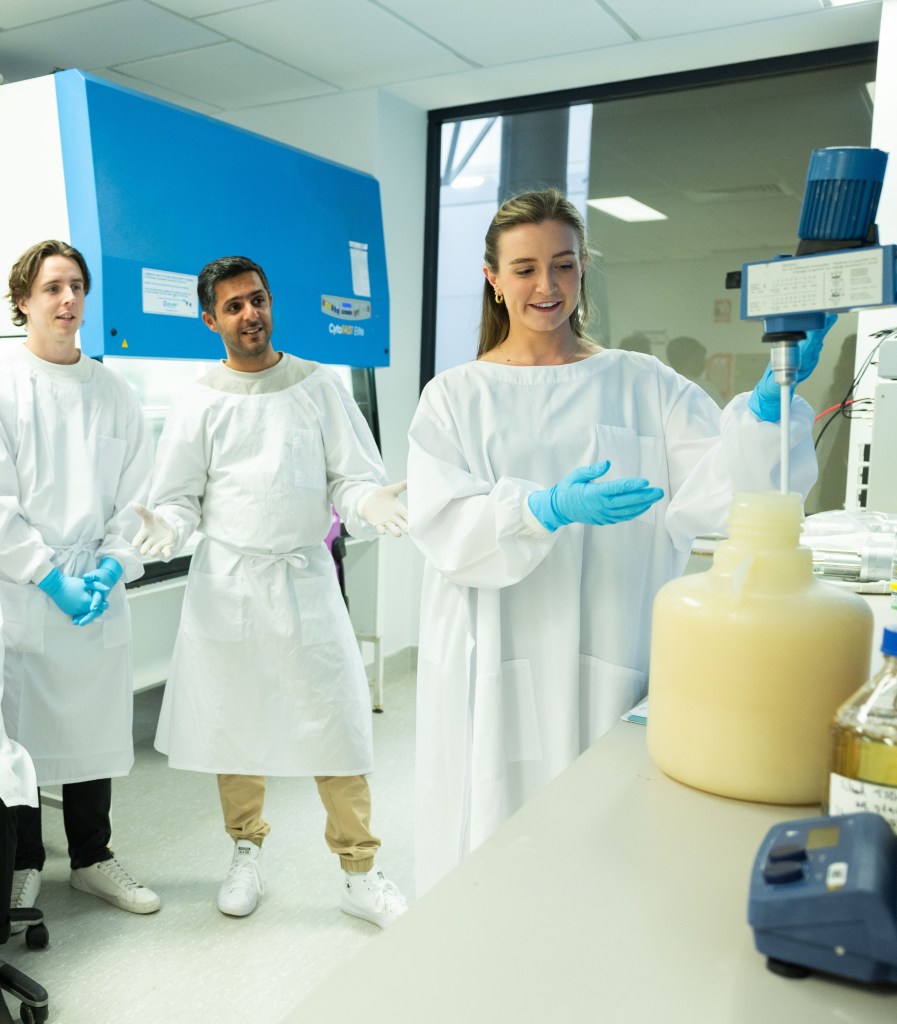

More than a quarter century later, the company they founded arising out of that experience, EnGeneIC, believes it’s on the brink of delivering a radical new cancer treatment that might finally overcome two of oncology’s cruelest dilemmas: how to kill tumours without devastating the rest of the body, and how to overcome treatment resistance.

Backed by $100 million in funding and promising early clinical results, EnGeneIC’s tiny bacterial “nano-cells” have started being dosed in a Phase 2a trial across a spectrum of the worst cancers, from pancreatic to mesothelioma, in 200 patients spanning Australia, Singapore and the US. And the results are suggesting that, maybe, they’re onto something big.

After Lee’s death, the careers that MacDiarmid and Brahmbhatt imagined for themselves as animal scientists – publication in top journals, professorships, perhaps a lifetime achievement award to cap it off – seemed suddenly empty. They found themselves going every night after work to the university library and pulling out everything they could find on cancer.

“We came up with a lot of different ideas and what the problems were,” Brahmbhatt tells Forbes Australia. “And the pennies began to drop.” He realised he’d seen things in his animal work that might help human cancer. An idea took hold that seemed revolutionary at the turn of the millennium: that they could hijack a harmless bacterial cell to smuggle super toxic chemotherapy drugs straight into tumours, sparing the rest of the body.

Their bosses at CSIRO didn’t want to support it, so they did what seemed equally revolutionary in 2001, they left their secure jobs and founded a startup, EnGeneIC, to tackle cancer.

With little more than a laptop and an idea, they walked into a lot of glossy foyers at the big end of town and were shown the exits with little hope.

“The things that impress me the most with the drug is how effective it is, how low the toxicity profile is and how easy it is to give.”

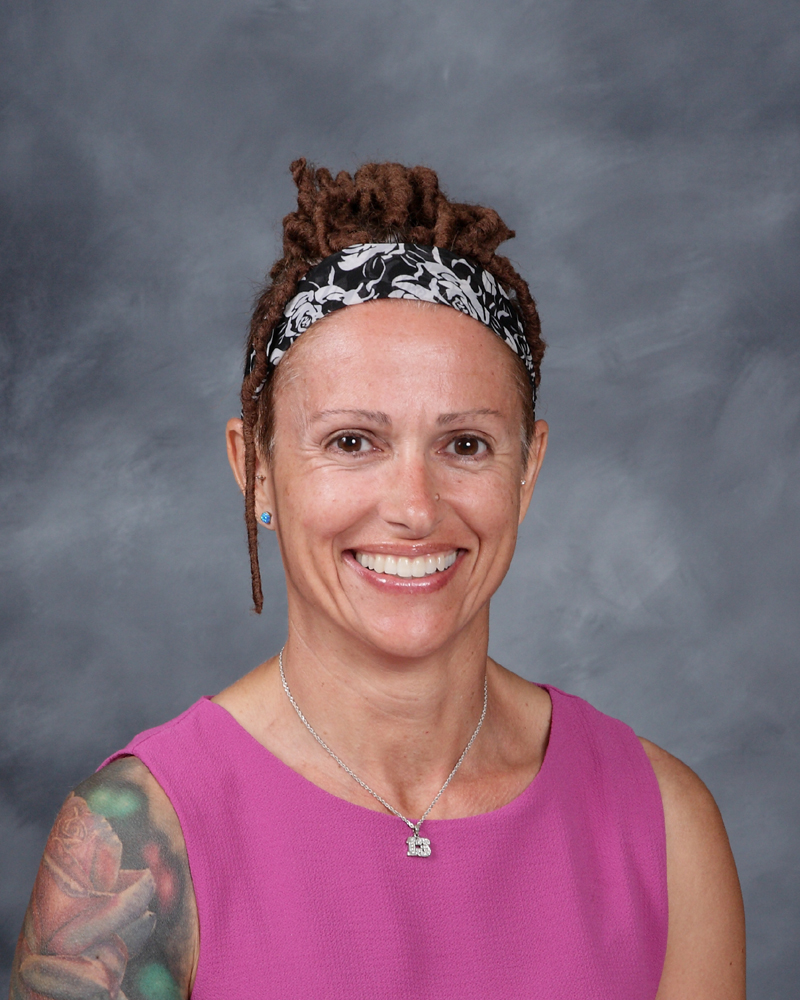

Professor Katayoun Moini, Chan Soon-Shiong Institute for Medicine

But Olympic sailor and businessman Mark Bethwaite saw something in them and became the first investor, helping them with a business plan and introductions.

They thought they needed $5 million to start EnGeneIC. After a year, they’d raised $4 million and figured that would have to do. They pulled up carpets and made the benches themselves with help from their partners and their mothers. And they set to work.

The Nano State

Brahmbhatt’s PhD had been in how bacteria divide. He’d seen that bacteria could sometimes split such that a tiny cell was created with no chromosomes inside it, and hence had no virulence. “It’s an empty sack, but with all the external topography of a bacteria. So that means it has a rigid cell wall, it has sugars on the surface onto which you can hang bispecific antibodies that can target another a cell – in our case a cancer cell.”

MacDiarmid says the first breakthrough came when they found a way to genetically alter bacteria to create the nano cells at will. “And we called this little nano cell or particle, the EDV, standing for ‘engeneic delivery vehicle’.”

Then they found they could load that empty sack with “super cytotoxins” that would be way too dangerous to use in normal chemotherapy. “But when they’re wrapped up in our rigid little nano cell, they are perfectly safe,” says MacDiarmid.

“The next step was to coat the EDV with an antibody that would recognise only cancer cells. What we hoped was that the EDV would lock onto the cancer cell and be swallowed by the cancer cell, then releasing the drug inside which would rush out and kill the cancer – much like a trojan horse.”

Their work developed quickly enough that by 2007 they were featured on ABC television’s Australian Story, in an optimistically titled episode, The Holy Grail. They’d had a lot of success with mice, and had eliminated or slowed brain tumours in 10 out of 10 dogs tested, but still hadn’t been in a human.

“There’s no doubts in our mind that it’s going to be a winner because the control arm is a horrible toxic drug.”

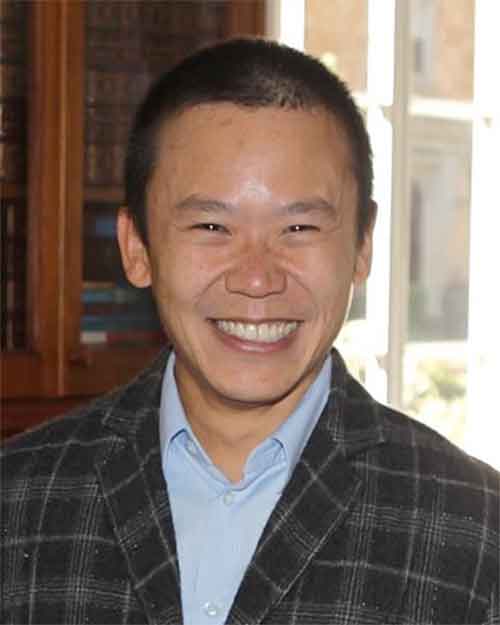

Dr Himanshu Brahmbhatt

Brahmbhatt was starting work at 5am and finishing at 10pm, seven days a week. “If I pursue any other hobby, like, I’ve got guitars sitting everywhere at home, but if I touch the guitar, I feel I am wasting my time, because somebody is dying out there and so I can’t seem to be able to do anything else,” he told Australian Story.

They said they hoped to have their revolutionary treatment approved in four years.

Triple threat

Brahmbhatt says cancer patients usually end up with multi-drug resistance. “They’re given first line, second line, every line they can think of, until the drugs no longer work and people are told to go home,” he says. “That’s not the case with us because the super cytotoxin overcomes drug resistance. And we’ve tested it in a myriad of solid tumours and it kills them all.”

But the nano cell has the potential to carry multiple different toxins. “So if some cancers are resistant to a particular payload, we can change the payload.”

While most cancer-targeting systems use protein or sugar molecules to attach to tumour cells, EnGeneIC’s is different. “There is nothing truly unique on the surface of cancer cells to identify them,” says Brahmbhatt. “The interesting thing about us is that we bypass that whole problem.

“Cancer has to feed itself, so it provokes a neighbouring blood vessel to create branches towards the cancer. It surrounds itself with new blood vessels, but these blood vessels are defective, because this is artificially built. So now the cancer cell is feeding itself voraciously, but these vessels are full of little holes which are just the right size for our nano-cell to drop out [of the blood vessel].

“So our nano-cell won’t drop out into the normal tissue, but wherever there’s a cancer is exactly where it drops out.” It’s physics, he says, as opposed to biology.

But wait, there’s more. And it is biology.

After the nano cell has done its Trojan-horse thing and been swallowed by the cancer cell and killed it, MacDiarmid explains, it leaves nano-cell fragments in the body, as published in Cancer Cell.

“Because the nano cell is derived from bacteria, we’re tricking the body into thinking it has a bacterial infection. It activates the immune system which has been shut down by the cancer … And because the bacterial matter is now in the cancer cell, the immune system’s killer cells start gobbling them up.”

Brahmbhatt interjects: “So now these killer cells run around and will find a single cancer cell anywhere in the body. They are so fast that everywhere we have seen these amazingly dramatic results.

“If I’ve got cancer, I don’t want to hear that for an extra three months of life I will suffer horrendous toxicity,” says Brahmbhatt. “I want somebody to tell me I can keep living.”

EnGeneIC co-founder Himanshu Brahmbhatt

“Once we have activated this immune system pathway, within weeks the entire tumour disappears, and that does not happen because of direct tumour killing by the nano cell. That happens because the patient’s immune system is now fully trained to recognise the tumour cells and to kill them.”

A survivor

Pancreatic cancer had spread to the lungs and liver of the 64-year-old Los Angeles mother of four. Three lines of chemotherapy over three years had failed. Professor Katayoun Moini at the Chan Soon-Shiong Institute for Medicine in El Segundo, California, applied for “compassionate use protocol” for an immunotherapy, but that didn’t work either.

The patient’s five-year survival odds were next to zero, Moini knew. And that’s when she heard about EnGeneIC’s EDV [whose name had by now morphed into EnGeneIC Dream Vector]. The patient had nothing to lose.

“She was requiring fluid to be removed from her abdomen every couple of weeks because of the cancer,” Moini tells Forbes Australia. “Our first clue after three or four months on the EDV was that the amount of fluid that needed to be removed declined, and ultimately she didn’t need to have it removed anymore.

“That was huge for her quality of life and then obviously her scans … We persistently saw that the disease was not spreading. That’s reassuring, and then just her performance status. When cancer is growing, people feel awful and the fact that she could resume a lot of her activities – visit her family, fly, go on long walks with her dog and her husband and kids, do Pilates – it was just outstanding to us and the fact that the treatment was so tolerable and that she wasn’t stuck here for hours getting it.”

Three years later, the patient is not out of the woods, says Moini. She’s still getting a smaller, weekly dose of EDV. Bear in mind that stage-4 pancreatic cancer has a 5-year survival rate of 2%.

“Big pharma have told us never to talk about the cost.”

EnGeneIC co-founder Jennifer MacDiarmid

“The things that impress me the most with the drug is how effective it is, how low the toxicity profile is and how easy it is to give. If you go to a cancer infusion clinic, they’re sitting in the chair for five to six hours getting chemo. It makes them feel sick. This is a 10-second infusion. And they feel fine.”

The patient remains the only one that Moini has used the drug on because of availability. She’d love to do more. “I know that Jennifer and Himanshu have the ability to do different types of targeted molecules. So I just think it has incredible potential.”

Oncologist Steve Kao, associate professor at the Chris O’Brien Lifehouse cancer centre in Sydney was involved with a study using EDV in 2017. He had one patient out of ten show a remarkable improvement in the always-terminal mesothelioma. But the EDV was carrying a different payload then – micro-RNA, as opposed to the chemotherapies they’re using now. “His tumour basically vanished and he got a clinically meaningful period of time where his tumour responded.”

Kao saw it as proof of principle that the EDV could deliver a treatment direct to a cancer cell, even if their micro-RNA wasn’t the best cargo. “That’s why EnGeneIC have used a different payload inside this vehicle now. And I think the improved payload hopefully will make a significant difference.

“It’s also exciting in that it’s tumour agnostic. It doesn’t have to be thought as a treatment that’s just for one particular cancer. There’s not many of those.”

‘Barbaric’ standard of care

One of the major difficulties EnGeneIC has overcome is that the only patients they’ve been allowed to treat have, like the Los Angeles woman, failed everything else first. “By the time we get people, at the third, fourth or fifth line of treatment, they are usually very sick and have organ damage,” says MacDiarmid. “But even so, we have had remarkable results. Our pancreatic trial in Australia where we had 17 people, we increased their overall survival by three times and those people had failed everything and were ready for palliative care.”

But the results are starting to be noticed.

“We are about to start another trial in America where we have been moved up,” says Brahmbhatt. The trial of 150 patients about to commence in the US will be at second line [that is, after first line treatment like chemo or radiation has failed].

It will be a Phase-2a trial, and unlike any cancer trial before it, it will take on a “basket” of the most terminal cancers because the EDV has shown promise against them all.

“The FDA has given us fast-track designation, so if this trial is successful the FDA will tell us to do a small registration trial and push it out to market because it is a completely unmet medical need,” says MacDiarmid.

They can justify the speed of approval because of the dismal prospects of patients with these most lethal cancers, like mesothelioma, glioblastoma and pancreatic.

“At second line, they only want us to demonstrate that we can increase the lifespan of those patients by an extra four months compared to the control,” says Brahmbhatt. “So you can see how bad these treatments are.”

MacDiarmid and Brahmbhatt are confident to the point of cockiness about being able to get over that low bar set by what they call the “barbaric” standard of care, and that they could be approved for sale by 2027.

“We should start getting the interim results early next year,” says Brahmbhatt. “There’s no doubts in our mind that it’s going to be a winner because the control arm is a horrible toxic drug. Compared to the control arm we are going to show no toxic side effect. In the control arm everybody’s suffering. These people will die very fast, whereas in our arm, even at end-state, people are surviving. So for us to show four extra months should be easy.

“If I’ve got cancer, I don’t want to hear that for an extra three months of life I will suffer horrendous toxicity,” says Brahmbhatt. “I want somebody to tell me I can keep living.”

At what cost?

EnGeneIC has raised $100 million to date but needs more. “The cost of clinical trials is absolutely eye-watering and it’s getting worse every two minutes,” says Brahmbhatt.

They also need to be ready to manufacture as soon as they get the go ahead.

“We are working with a couple of CDMOs, contract development and manufacturing organisations, in Australia. We’re trying to stay Australian. We could do it ourselves but that would cost $200 million.”

Brahmbhatt says it will take another $80-$100 million to get to market. “But simultaneously we are preparing for big pharma licensing. Now, the technology is completely de-risked. They simply have to push it through to market. Consequently, many of the big pharmaceutical companies in the United States and Europe are looking at us very closely. And many of them have already told us that they will wait to see the interim data from our American trial.

“But as another backup plan, we have also been preparing for a potential NASDAQ listing. Our lawyers in New York are preparing our S-1. We have got a chief financial officer in our New York office where all our finances have been turned into US GAAP [generally accepted accounting principles] accounting, so that Trump doesn’t throw a tariff on us. We’re playing at each of these areas whichever comes through.”

The cost of EDV would be much lower than conventional chemotherapies, Brahmbhatt says. “Big pharma have told us never to talk about the cost,” says MacDiarmid. “Because the differential for them is much bigger than you think.”

But Brahmbhatt says they will always speak plainly. “They tell me to shut up, but I’m only speaking the truth. The truth is we will decide how much to charge.”

And how much of the company do they still own?

“We’ve been diluted to buggery, but you know, we have put all our money into the company, not only the intellectual property. So we are still holding on to 9% each.”

And as for those 16 hour days, they’re still happening. “Given that we are embroiled in clinical trials in a range of different cancers, the workload hasn’t changed,” says MacDiarmid. “In fact, the science never ends with new developments all the time and the quantum of funding required means our efforts need to continue 24/7. However, we both thrive on these challenges and don’t know how to live any other way.”