BRANDVOICE – SPECIAL FEATURE

By Professor Richard Hall

In business, we tend to romanticise leadership and marginalise management. Leaders are visionaries. They disrupt markets, break moulds, and inspire movements. Managers? They’re often cast as bureaucrats, focused on the mundane—spreadsheets, budgets, performance reviews.

It’s a seductive narrative. But it’s also flawed. Because while leadership may set the direction, it is management that gets you there.

The truth is this: leadership and management are distinct disciplines. They each have their place. And when used well—when understood as complementary rather than hierarchical—they produce cultures that are not only innovative and dynamic but also resilient, consistent, and high-performing.

Leadership is about change. Management is about consistency.

Let’s start with the fundamental distinction.

Leadership is the art of influencing people toward a common purpose, especially in times of uncertainty, change, or challenge. It’s future-oriented. It’s about direction, meaning, and belief. Leaders frame context and focus on what’s important. Leaders help people make sense of complex environments, navigate ambiguity, and stay motivated when the answers aren’t obvious.

Management, by contrast, is the process of planning, organising, and executing tasks to achieve defined outcomes within known parameters. It’s present-oriented. It’s about systems, discipline, and reliability. Managers ensure that strategy becomes output—that what gets promised, gets delivered.

John Kotter, Professor Emeritus at Harvard Business School, famously argued, leadership is about change, transformation and inspiration, while management is about stability, consistency and execution.

Both are critical. But each is suited to different kinds of problems—and misusing one where the other is needed is a recipe for organisational friction.

Sometimes it’s useful to think about the kind of problem or challenge you’re facing – is it complicated or complex? A complicated problem is tricky, but a solution is known or knowable. A complex problem is ‘wicked’, in the sense that no known solution exists. Management is well suited to complicated challenges, but when it comes to the complex, it’s time to lead.

The myth of the “natural leader” — and the neglect of management

Over the past two decades, a leadership industrial complex has emerged—books, podcasts, TED Talks, Instagram posts—all promoting the cult of leadership. The ideal leader is purpose-driven, emotionally intelligent, a master of storytelling, a servant first and foremost. They spark transformation. They build culture. They elevate others.

All true—and all important.

But this focus has come at a cost: a generation of leaders uncomfortable with, or dismissive of, the hard and often thankless work of managing.

This has real consequences. Gallup’s State of the American Manager report in 2015 found that:

“70% of the variance in employee engagement is directly attributable to the manager.”

That’s not about charisma. That’s about execution—setting clear expectations, giving feedback, managing conflict, ensuring accountability. These aren’t “soft” skills. They are the “hard” skills – and they’re the difference between a good culture on paper and one that performs under pressure.

When you should lead

Leadership is most valuable when the path forward is unclear. In these moments, people look for someone to make sense of complexity—to interpret what’s happening and chart a course forward.

Lead when:

The business is in crisis or under external threat

There is strategic ambiguity and multiple plausible paths

The organisation is undergoing transformation or change

The mission is in jeopardy and people have lost belief

There is emotional turbulence across the workforce

In these scenarios, what matters most isn’t technical expertise or process discipline. It’s sensemaking and emotional resonance. Leaders don’t always have the answers—but they create the conditions where answers can emerge. And the best leaders help their people to be the source of those answers. They know that everyone’s best thinking is needed to respond effectively to complexity.

Research from McKinsey confirms that during transformation, “inspirational leadership” is one of the four behaviours that distinguish successful leaders from average ones. In organisations that delivered strong financial performance during change, these behaviours—vision-setting, role-modelling, capability-building, and empowerment—were far more present.

When you should manage

Similarly, a meta-analysis led by Zhu Newman and published in the Journal of Applied Psychology in 2018 found that transformational leadership significantly boosts team adaptability and innovation, especially under conditions of uncertainty and pressure.

This type of leadership isn’t performative. It’s grounded in purpose, presence, and the ability to mobilise others when the road ahead is foggy.

While leadership creates movement, management ensures momentum. It matters most when direction is already set and the challenge is one of execution, not inspiration.

Manage when:

Objectives and expectations are clear, but performance is lagging

Systems and workflows need to scale or become more efficient

Roles are ambiguous and execution is inconsistent

Team engagement is low due to unclear accountability

You’re operating within high-risk, highly regulated environments

In these contexts, people don’t need vision—they need structure. They need to know what success looks like today, what’s expected of them, what the top priorities are and how to course-correct if they fall short.

And this matters deeply to employee experience. According to Gallup’s 2019 Re-Engineering Performance Management report:

“Only 21% of employees strongly agree that their performance is managed in a way that motivates them to do outstanding work.” Employees don’t leave organisations, they leave managers.

Poor management isn’t a minor inconvenience. It undermines trust, dulls commitment, increases attrition, and costs the business dearly. By some estimates, disengaged employees cost the global economy US$8.8 trillion in lost productivity every year, according to Gallup’s State of the Global Workplace, 2023, report. And that disengagement can easily become corrosive and contagious breeding a culture of cynicism and failed expectations.

So, if your team is underperforming, check the management systems before assuming a lack of leadership is to blame.

Why the best executives are fluent in both

The world is not static. Neither is your business. That’s why the most effective leaders are situationally agile. They know when to lead and when to manage—and they can switch between the two seamlessly.

This is sometimes referred to as “ambidextrous leadership.”

A 2017 study published in the Leadership & Organization Development Journal titled Ambidextrous leadership and innovation found that organisations with ambidextrous leadership—those capable of balancing transformational (leadership) and transactional (management) approaches—outperformed others on innovation, employee satisfaction, and long-term adaptability.

It’s not about being all things to all people. It’s about developing range. When you over-index on either mode, your leadership becomes brittle:

Too much leadership without management? You get lofty vision and poor delivery. Chaos.

Too much management without leadership? You get efficiency without evolution. Stagnation.

Consider the CEO who brilliantly repositions the company strategy, but fails to ensure that middle management has the resources and training to execute. Or the high-performing manager who drives results today but can’t inspire the team toward a bold new future. Both scenarios fail.

The cost of getting it wrong

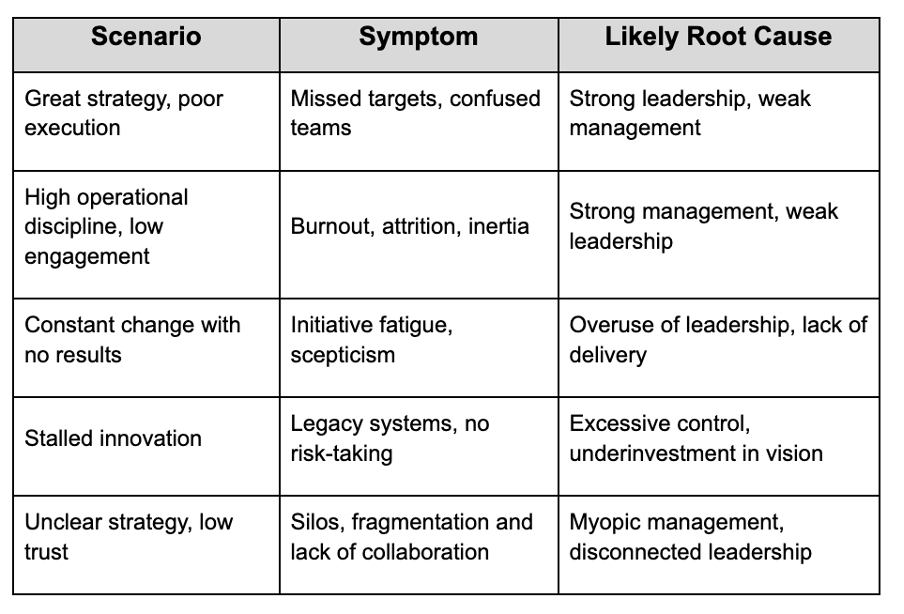

Let’s get practical. When leadership and management are misaligned, here’s what you see:

Knowing which hat to wear—and when—isn’t just an executive competency. It’s a strategic imperative.

What this means for organisations

The implications are significant for how we hire, promote, and develop talent.

Don’t conflate leadership potential with promotion readiness.

A brilliant strategist who can rally people may not yet have the management muscle to deliver results through others. Give them the support to build it.

Stop thinking of “manager” as a dirty word.

We’ve glorified leadership so much that capable, operationally focused professionals are sometimes overlooked for senior roles. That’s a mistake. Some of your most effective executives will be quiet operators—not charismatic evangelists.

Design development programs that build range, not personas.

Most corporate development programs over-index on leadership theory and underinvest in management craft. It’s not either/or. Build fluency in both.

Reward performance, not posturing.

Leadership isn’t about who speaks the loudest in meetings or who gives the best keynote. It’s about who delivers impact—strategic or operational—when it matters most.

Recognise ‘quiet leadership’ and promote dedicated managers with the right values. Many years ago Jim Collins, author of the book Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap and Others Don’t, identified ‘Level 5 leadership’ as epitomising the combination of professional will and personal humility – a dedication to serving and stewarding the organisation and its people.

For Collins, the best exemplar of Level 5 Leadership is someone you’ve probably never heard of – Darwin Smith – Kimberly-Clark CEO who, for decades, led the company to consistently outperform its competitors year after year. Smith was humble, mild-mannered, but fiercely dedicated to service and quiet excellence.

Not flashy, but incredibly effective.

The call to action

It’s time to stop pretending leadership and management are synonyms. They’re not. And in a world that’s simultaneously volatile and performance-obsessed, organisations can no longer afford to ignore the distinction.

The best leaders I know aren’t always leading.

They know when to manage. They know when to get out of the way. They know when to inspire—and when to get the job done.

That’s not ego. That’s maturity.

And it’s the kind of leadership we need now more than ever.

Professor Richard Hall is Deputy Dean, Leadership and Executive Education, at the Monash Business School.