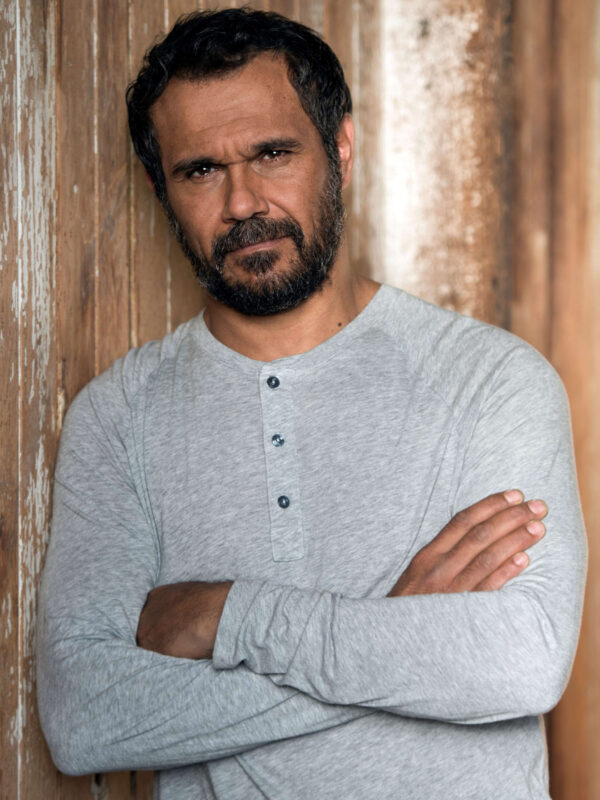

Aaron Pedersen is arguably one of Australia’s most distinctive, quietly influential and possibly complex actors. He went from a rough childhood in Alice Springs to ABC TV Journalist to one of this country’s most recognisable, outspoken indigenous voices. He told Stewart Hawkins about the motivation driving him to succeed, his definition of “divine masculinity”, the actual problem with Australian race relations and why his brother brings him real happiness.

This story appears in Issue 19 of Forbes Australia, out now. Tap here to secure your copy.

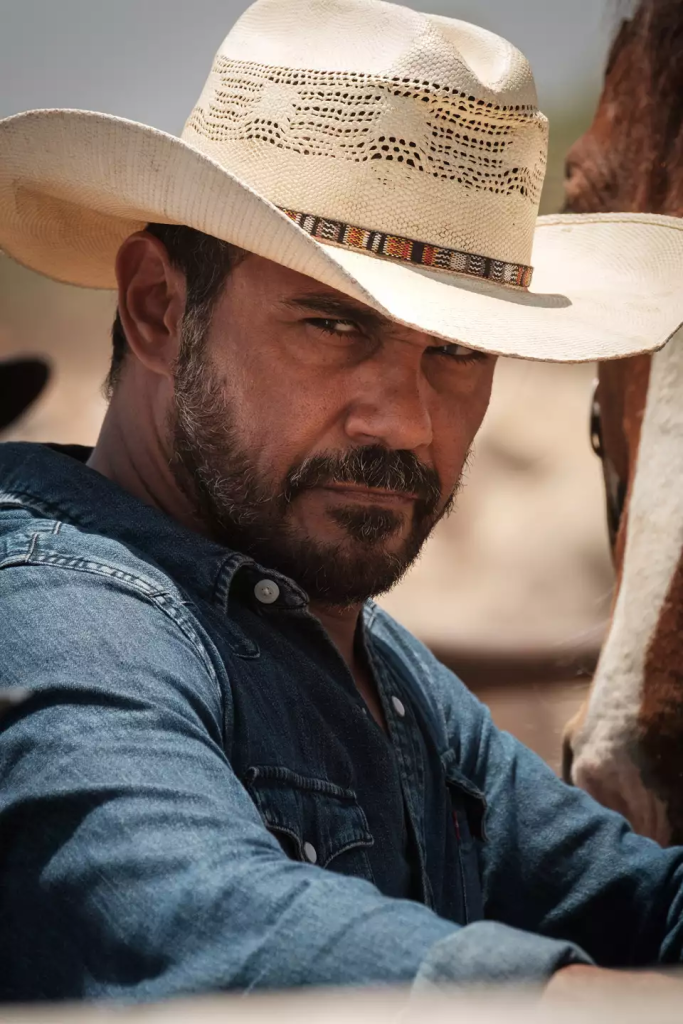

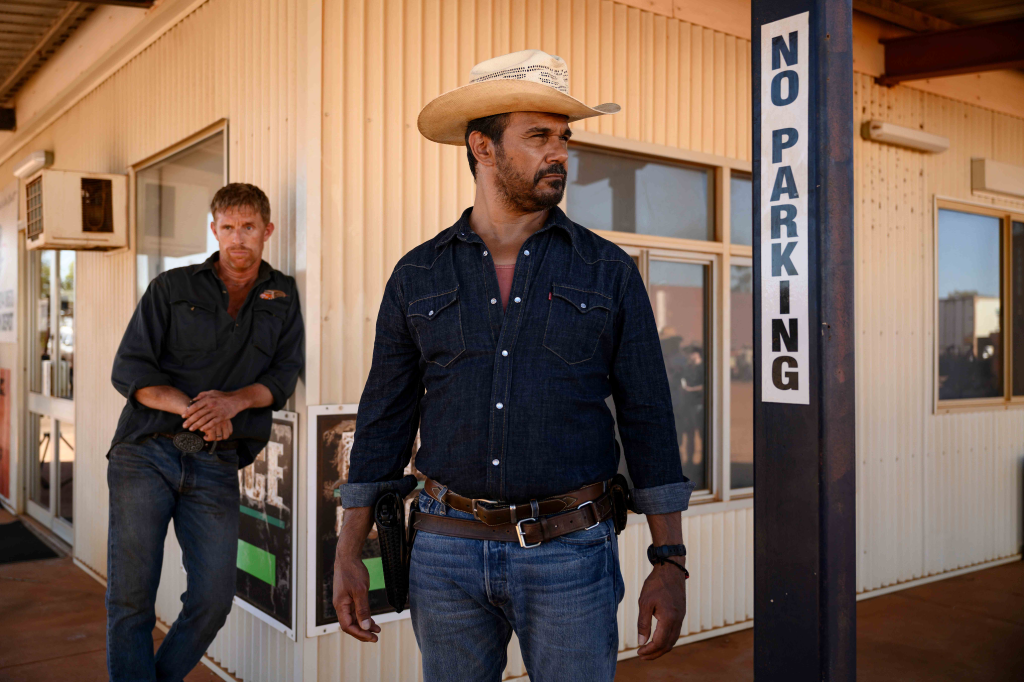

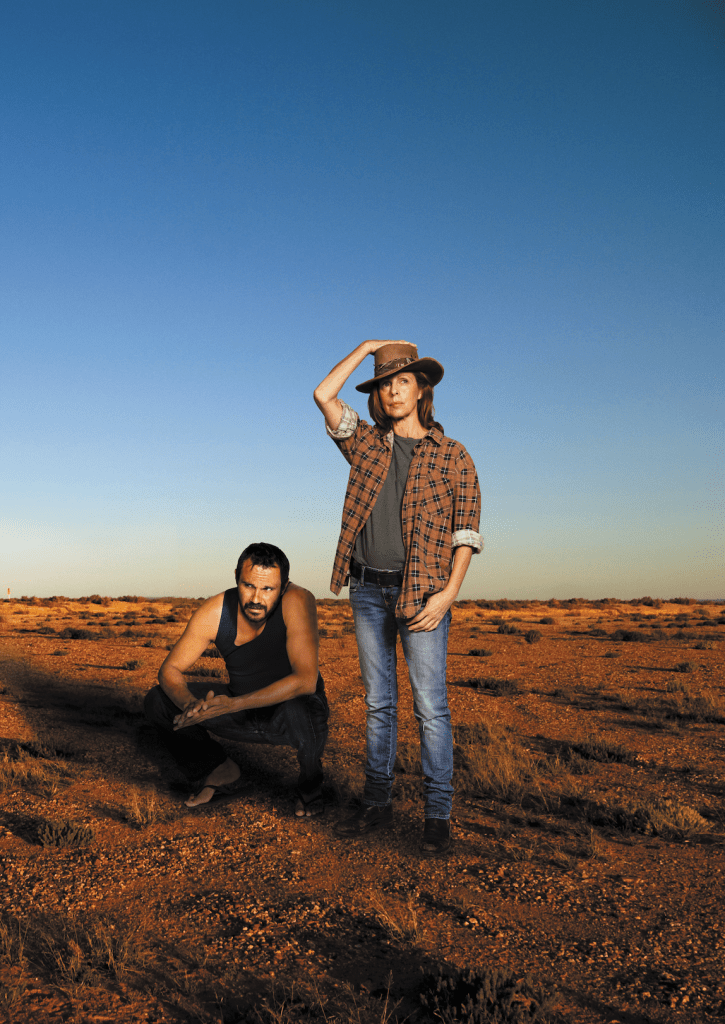

In the opening scenes of the celebrated ABC TV series Mystery Road, Aboriginal detective Jay Swan is looking for clues around an abandoned ute in the middle of a vast plain of cracked dirt; cowboy hat, denims, handgun on his hip.

He’s not giving his fellow white cops (who include a senior sergeant played by the legendary Judy Davis) an easy time of it.

Swan, portrayed by Aaron Pedersen, is a brooding, taciturn, simmering man, monosyllabic in his answers with a default grumpiness that suggests profound inner hurt and discourages much conversation anyway.

A decade or so after that episode first aired, we’re having lunch at the restaurant at the end of Sydney’s Wharf 4/5 with its sweeping views of the harbour. Pedersen’s about to start rehearsals for a Sydney Theatre Company production of the iconic Australian story “The Shiralee”.

It’s a reunion of sorts. I first met Pederson as a young ABC cadet journo three decades earlier, about the time he was deciding to shift to a career in acting.

I told him not to, too insecure an industry, limited opportunities, sporadic superannuation payments.

He ignored me.

Good choice.

I already knew Pedersen’s history in outline; there was nothing easy about the way he’d made his way in the world, and I had to ask him at his present stage in his career – how much of the angry, damaged Jay Swan was actually him?

“I think a lot of it. Yeah,” he says.

“The character for me was my silent conversation with this country. I thought [Swan’s] conversations were a lot louder when he said nothing.

“I think that that character is the country and how we, as indigenous people, perceived this land and perceived the atrocities that happened and the lack of acknowledgement and all that stuff.

“Even though I’m an actor, I’ve got to acquire my tools from somewhere in my life. I never went to drama school.”

That afternoon, we decided to give that “silent conversation” some voice.

Pedersen has been controversially vocal in the past, echoing the sentiments of Churchill Fellow Sarah Maddison that, in his words, “Australia doesn’t have a black problem, it has a white problem.”

“We know who we are, but white Australia doesn’t really know who we are.”

Pedersen’s point is that white Australia hasn’t really taken the time over the years to understand who Aboriginal people really are and what makes them tick, what motivates them as people, what their incentives and understandings are.

He says it’s based on land and spirituality, something difficult for people to grasp if they’re living in a materialistic world, a capitalist society.

I asked him what he thought the country should be – what would that look like?

He says it should celebrate walking with the oldest continuous living culture in the world: “That’s gotta be a gift,” he says.

“The country should understand its maturity and believe that it’s in an amazing place. I’ve always wanted this country to embrace and join us in the journey that we are all a part of together. It only makes for a better nation.”

What does that celebration look like?

“Treaty, full acknowledgement. They call us Aboriginal, but they don’t really necessarily acknowledge us as the original inhabitants of the land. It’s got to look like humanity.”

Growing up black in a white world

Pedersen was literally born on a plane landing in Alice Springs – a portent of a mercurial career? – three years after the 1967 referendum that recognised Aboriginal people in the constitution. While Pedersen considers himself lucky to have been born after the referendum, before that, he describes indigenous people as being treated basically as enslaved people – that “luck” was only relative.

He had seven siblings and was in and out of multiple foster homes. He confesses he was “rattled” and “knocked around”. He doesn’t talk about it directly, but somehow you can see in his eyes that in the time he spent as a “street kid”, he’d seen things that both made him profoundly sad but also strong, tenacious, and in his words slightly “belligerent”.

He says even then, he thought there was a better world out there, but he didn’t understand the politics.

He did understand the divisions, though. He was acutely aware of the racism in Alice Springs.

“I had had to source all my belief from within myself,” he says.

“I had to believe that everything was possible, and I never listened to anybody in relation to their negativity. I spent a lot of time by myself, and I spent a lot of time with my thoughts, especially when I was on the streets, living in the homes.”

The wheel of life turned for Pedersen when he asked his caseworker if he could go to boarding school, to get out of Alice Springs, and he was sent to Hamilton in Western Victoria.

He didn’t get great grades, and he passed year 12, only just. But that wasn’t entirely the point; he had his own goals.

He had meals every day, he had a roof over his head, he had a warm bed, and he had his own independence in a way. The fact that those basic things spoke volumes to him casts a bleak perspective on what must have preceded it.

“It was a great experience,” he says. “It was there that I started my journey towards individuality, but also my journey towards what my life was going to be like and what dreams I was going to chase.”

It was careers day, and he mentioned he wanted to be a PE teacher or a paleontologist, but also that he wanted to work in TV. There was a journalism cadetship for the ABC under an equal opportunity scheme going.

He applied for it with help from “Mrs Bell from the library”.

He got it, moved to Melbourne where he started working as a sports reporter and then moved to Adelaide to, as he puts it, be a big fish in a smaller pond.

“I just had this fire in me. I wanted to champion for change in my own life,” he says.

A greater truth in fiction

Pedersen is now in a position where his voice has gravitas, is actually listened to, and for him, there are at least two important reasons acting was a more effective stage than journalism.

One was connectivity.

He believes that for some white Australians, the arts might be the first contact that they’ve had with any indigenous person, and it’s a less confrontational pathway because they choose to engage in that world anyway.

“From that, I believe, I hope, that over the course of time I’ve changed a few people’s lives just through being in their lives, through the arts,” he says.

The other is being able to tell stories.

“I always thought I was telling indigenous stories anyway. It was my walk, my talk, my attitude.”

In his teens, he remembers being drawn to the arts through television, seeing people like “Uncle Bob” (actor, playwright and activist Robert Maza) on the screen.

“I remember seeing him in I can’t remember what, but he was playing a lawyer. I just remember this brief moment in my life where I was like, Wow, that’s what I want to do,” he says.

He was around 24 years old when he made the shift to acting.

“I just wanted to give it a go. I said, you know what? They call it coloured television. But I used to ask myself, where are all the coloured people? I thought there was a niche that was available. I believe that there was an opportunity for an indigenous actor to be in the mainstream.

“I never thought of it as being a career where I didn’t have stability. I didn’t go in with too many negativities on it. I just believed that it was possible and that it was about time that change should happen.

“I just had this fire in me that I just wanted to change the dynamic of Australian mainstream television. I certainly dreamt big.”

News had set him up for a television career, he went over to the Blackout program at the Gore Hill office in Sydney – an early indigenous program developed by the ABC.

He auditioned for Heartland. He got a part, not the one he auditioned for, but he got to work with Bob Maza, Cate Blanchett, Justine Saunders, and Kevin Smith.

“I was pretty wooden, but that’s okay,” he laughs.

“You’ve got to start something. If I’m an apprentice carpenter, my table’s going to have a wobbly deck. The joins aren’t going to be all smooth. But it doesn’t collapse.”

The film Dead Heart with Brian Brown followed.

Then another wheel turned in his life, and he got the role of detective senior constable Michael Reilly in Water Rats.

Pedersen describes this role as being one of the first “non-indigenous” roles on mainstream TV to be played by an indigenous person – he makes a point of acknowledging the filmmakers and producers who took a chance and ‘normalised’ a black actor.

“I think a lot of indigenous people who saw it thought that too,” he says.

“That was the beautiful thing. That was a big step. It was a massive step. I think about it now.

I believe that Australian audiences were hungry for more.

“We shouldn’t even be having this conversation about affirmative action policies that allow Aboriginal people to participate in the workforce. That shouldn’t even be a question. That shouldn’t even be a conversation. It should just happen. I think that’s what has been the big fight for me, just to make it as normal as possible.

“Did I have trepidation about stepping into this industry? No, I didn’t. And I don’t know why I never asked myself that question. I always thought that I’d come up against a lot of challenges in my life anyway, so I was just ready to face them.”

The Happiness Guru

While Pederson has this brooding, serious, don’t-mess-with-me persona, it doesn’t take that long for the cracks to start showing, particularly when he talks about his brother Vinny: “13 months and 24 days” younger than him.

Vinnie, who has cerebral palsy, enters the conversation, ironically, when I ask him about ambition and what success means to him.

“I came into the game with ambition, and I’m kind of not as ambitious as I used to be, because for me, my reality is my brother, Vinny, who I look after,” he says.

“I used to look across at him and think shit, there for the grace of God, he needs my help. He needs my guidance. I can’t abandon him. He gave me this duty of care without me even realising it.”

Pedersen says he wanted to build a better world for his brother, and it became an incentive because he knew that if he didn’t clearly understand where his “journey was going” and what he was going to do with his life, then it wasn’t going to work out well for Vinnie.”

But it’s not a one-way street, by any means.

Pedersen’s face lights up and he smiles broadly for the first time in the interview, talking about what Vinnie means to him and what his brother’s taught him through his unique perspective on life.

“He’s not afraid of anything,” he says.

“He loves life more than anyone I know. And I think my journey with my brother Vinnie has filled a void of my father not being there in my life. Vincent was my benchmark and my reminder that I got to get my shit together.

“He’s been my guru of happiness.

“He loves this world. He loves the art. He loves being famous. He loves people. He’s a hundred per cent present. What an incredible gift to have someone like that in your life.

“My relationship with my brother Vinny is evidence that there is divine masculinity. He’s not afraid of showing me that he loves me 10 times a day.”

Solutions to an intractable problem

So, as the coffee arrives, I ask him what the solution to the black and white divide in Australia is. How do we fix it?

His answer is maturity.

“How do I describe maturity?

“Having love in your heart, having understanding, realising that we should just see each other as mirrors.

“I believe there’s one country, it’s called Earth. It’s one race. It’s called the human race. And that’s it. I can’t understand the divisions. I don’t understand the borders. We make this up.

“The problem is we built that castle and it’s full of corridors and doors and cages and locks, which are just so complicated to unravel.”

The Shiralee

Pedersen’s latest role is back in the theatre in the Sydney Theatre Company’s production of D’Arcy Niland’s 1955 book The Shiralee, adapted for the stage by Kate Mulvany.

It’s a return to the stage, which he says he loves.

“I don’t think at any point I ever thought, well, I’ve made it,” he says.

“I’m excited about the next 10 years. I’m in an age group that offers a lot of very interesting characters. I think it’s a lot harder when you’re younger, because there are only a few roles around, whereas as I get older, I think maybe, hopefully, there are more interesting characters. Not just indigenous characters, but characters.”

Which is a good thing because he’s playing six roles in this new show, and he was excited to work with young director Jessica Arthur.

But, at the end of the day, it comes back to narrative.

“I love theatre. I love the intimacy aspect of it. I love the immediacy of it,” he says.

“But I think for me, this is just storytelling. It is a white Australian story, but it is a classic Australian story. You’ve got to give it that.”

Showing 6 Oct – 29 Nov 2025 at Drama Theatre, Sydney Opera House

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.