While gyms are closing across Australia, Joy In Movement is booming. Its low-cost infrared studios and automated classes have created a boutique fitness blueprint.

The lights are red and dim. The room is hot. Five of us are panting away on mats, skin glistening like a 3am dancefloor.

But it’s 8am in what is arguably the fastest-growing fitness franchise in the country, Joy in Movement, or JIM. What began as a single experimental heated room in a Cronulla gym has in two years become a 20-location network stretching down the east coast — with 15 more set to open by the end of summer, according to founder Jarad Hobbs.

While infrared saunas are enjoying a moment, the breakout success of Joy In Movement is all business model – tiny 50-square-metre studios, automated video-led classes 5am to 9pm seven days a week – delivering the kind of unit economics that Hobbs says makes his clients “do the math on the mat”.

JIM is entering a market facing strong headwinds. The number of gyms, fitness centres and yoga studios in Australia fell by a whopping 13.3% in the last year, after experiencing massive growth in the previous decade, according to Ibis World data. About 1,012 such businesses [out of 7,595] ceased trading in the past year.

They’ve been squeezed by market saturation, competition from home gyms, falling discretionary spending, rising costs and franchise stress.

But Hobbs wasn’t thinking about any of this when it all began. He was thinking about the 40-year-old mums who have been lost to the fitness world.

So his lights are turned down low. There are no mirrors, so nobody should feel too bad about shedding layers. The classes are short for the time poor, and they aren’t hard.

Even if you need a break, the video coach is as non-judgie as the best AI.

Hobbs has combined the many claimed [but often disputed] benefits of infrared saunas – like heart benefits, improved circulation, glowing skin, detoxification, faster recovery and reduced inflammation – with those that are proven to accrue from exercising in the heat, like boosted cardiovascular load, increased flexibility and accelerated calorie burn.

And all this from a guy who hates hot yoga.

Too long, too hot, too woo

Hobbs left school early and fell into the fitness industry. He opened his first personal training studio at 19. “But I was more passionate about the business side than the training side,” he tells Forbes Australia.

He toyed around with a few business models before, at 24, he launched a boutique group-training franchise.

“It was like 100 members in a small space, one coach. It worked really well in one location, but failed in another. It wasn’t because of the business model, it was more because I wasn’t able to get the operations manual in place and the training and the detail … I tried to launch three at once and it was just chaos.”

Hobbs went back to his standard group-training gym, Burraneer Fitness, at Cronulla in Sydney’s south. But he kept toying with different fitness models and ways of running a studio, still looking for the big idea. He had the “JIM” name long before the concept.

“We’re aiming for a thousand locations in the next four years. It sounds ambitious, and it kind of is, but it kind of isn’t when you look at the economics of the model.”

Jarad Hobbs, JIM founder

“I flipped my studio to a more functional studio in 2013,” he says. “But I didn’t want to be like an F45. I wasn’t gonna do a franchise if it wasn’t unique, not just a different colour logo.”

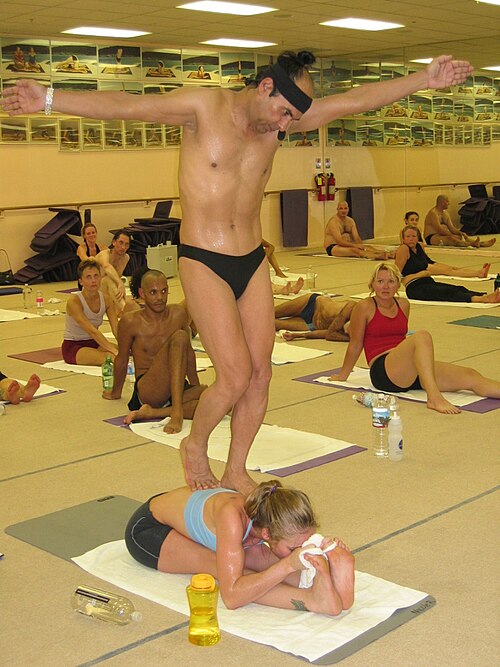

Female clients were coming to him saying they wanted to do more stretching. He thought about the idea of doing it in a hot environment. Bikram Yoga – hot yoga performed in studios heated to 41 degrees – had come to Australia in 1998.

“I liked the idea that being in a heated environment increases your circulation so you move better.” He went along to a class, but hated it. It was too long, too hot, too woo-woo. “And it was way too hard. The movements were too challenging. There was the crazy flexible instructor at the front folding in half.”

There were mirrors, bright lights. “The experience was terrible … but I still liked the idea of movement in the heat with low impact. That made sense from a sports-science perspective.”

He built an experimental hot room at his gym. A guy he consulted about how to build it suggested he try infrared heat instead of air conditioning.

“Then what happened was really interesting. I tested a few stretch classes, and realised it felt very different from hot yoga and not actually understanding why.”

The bloke who sold it to him explained that there was no humidity. That the radiant heat warmed the body without heating the air. That explained why he could breathe so comfortably. And if he could breathe so easily, what was stopping him doing a workout in it?

“That was the light-bulb moment,” says Hobbs.

He started to test it with weights and functional fitness classes. “People were coming back to me and saying, ‘My skin is better.’ ‘I’m sleeping better,’ or, like, ‘My aches and pains are better’.

“I’d never heard that before, and I’ve been in the fitness space for 20 years. I started to look into the infrared benefits, and it became obvious … because it penetrates the skin, it’s actually pulling heavy metals and toxins out of your skin.”

“So we’re getting both the infrared benefits and the benefits of exercise … So it was like, okay, we have a unique product.”

Hobbs thought he couldn’t be the first person to think of this. He Googled it and found Hotworx [founded in the US and which now claims 800 locations worldwide]. It offers the full gamut of yoga, pilates, functional fitness and weights in multiple infrared saunas across each gym.

Far from being disappointed, it made him feel validated. His would be different. He kept testing. How long? How hot? How the music worked.

The second big idea was doing away with a teacher. There’d just be a video screen at the front on rotation, with 30-minute classes on the hour.

It would run seven days a week, 24 hours, each day of the week being a different routine.

“The big one, from a business perspective, is that we can operate in 50 square metres, which is a third the size of a group-training model.”

He brought in a silent partner with experience in growing a fitness business. The partner got him sorted with the backend details that Hobbs had failed at the first time around. “I actually didn’t need investment. I was more looking for a partner to help drive it.”

Maths on mats

Because he’d tested it at his own studio, Hobbs never actually ran a JIM himself. The first two JIMs to open, in July 2023, were both franchises.

Hobbs says he’s sold 53 franchises with 10 more reserved. The 20th franchise opened in Coffs Harbour on the NSW north coast in early November.

“Four more will open in December, and then we have another 10 … who will be opening in January.”

He charges a $50,000 franchise-establishment fee and says the average cost of getting started is between $200,000 and $250,000.

Joy in Movement is currently spread down the east coast from the Sunshine Coast to Melbourne, with none to the west.

Hobbs’ ambitions are for 500 territories in Australia, plus an international expansion. “We’re aiming for, like, a thousand locations in the next four years. It sounds ambitious, and it kind of is, but it kind of isn’t when you look at the economics of the model.”

The average membership is $50 a week and the average is about 150 members per location, Hobbs says. “We can let people do the math. Like in our Botany location, there’s 230-odd members. People who have the business acumen or that entrepreneurial kind of spirit, they’re going, ‘Wait, how much is the rent here?’ They’re literally doing the math on the mat.”