Thomas Edison topped our list of America’s 250 Greatest Historic Innovators. To honor that, we present an interview from our June 15, 1929 issue in which he predicted solar power and electric trains.

The original layout from June 15, 1929

Electrical Power Straight from the Sun, Edison’s Prediction

Light and Power Industry a “Baby” in Its Evolution—World’s Greatest Inventor Expects to Be One-hundred—His View of the Future

By Dudley Nichols

“Edison is always thinking,” Dudley Nichols wrote. “That is one of the remarkable things about him.”

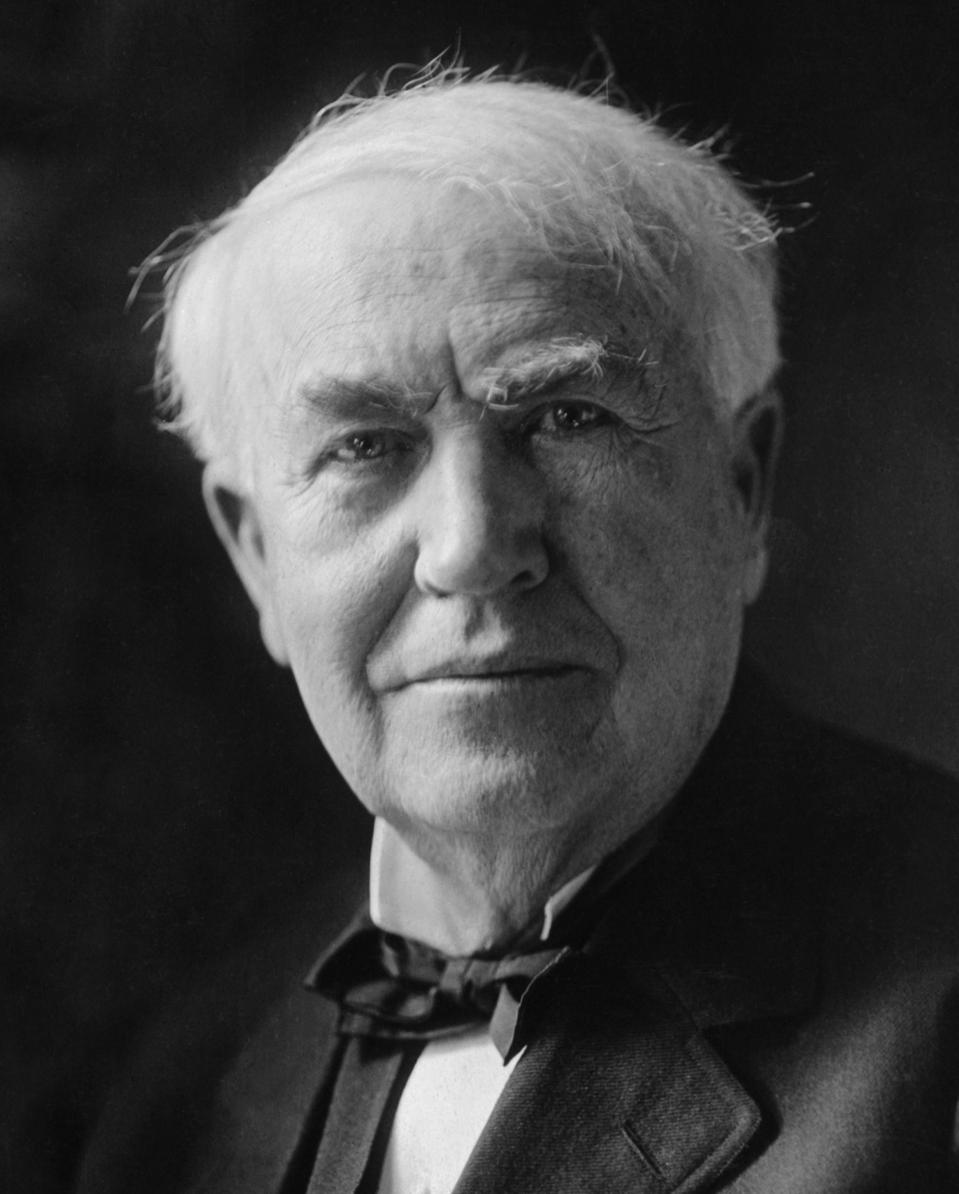

Bettmann Archive/Getty mages

After more than fifty years of uninterrupted fertility in invention, during which he has not only begotten but continuously fathered the electrical era, Thomas Alva Edison believes that we have only reached the sandy beach of the great new Epoch of the Volt and Ampere, that we have only wet our shins in the ocean of invention and discovery.

At the age of eighty-two Edison, the greatest inventor the world has ever known (for there has been no single crest to his career), a radiant old man with the warm gaiety of a boy in his fine large face and the mental concentration of a young man in his clear blue eyes, told the writer in a special interview for FORBES some of the things which have been at the back of his mind concerning the way the world is going to go.

For one thing, Edison believes the time is coming when mankind will draw electrical energy on a large scale directly from the sun. Ever since the age of steam started the world to rolling at a heightened speed, so far as man is concerned, we have been drawing on the bank account of old sunlight. Coal is sun energy which was stored long ago in vegetation, petroleum is the same thing stored in low forms of animal life. But like all bank accounts they can be overdrawn, though Mr. Edison has no fears for the safety of mankind along this line.

“Man will always be able to create from Nature as much power as he will need,” he said, and he went on to point out some of the ways in which we shall be able to cash in on our current revenue from the sun, which is for the most part wasted, as if we were beings who walked in a constant golden shower of money and yet were unable to stoop and pick up a single coin.

Man will not only find a way of picking up all this “money,” Edison believes, but he will find other means of deriving immense energies which he will demand in increasing quantities as his intelligence expands and craves more power over Nature.

Edison, who was eighty-two years old last February 11, missed his annual birthday interview with the press on that date for the first time in decades. That birthday interviewing had become an institution for the metropolitan press. Reporters went from New York, Chicago, Philadelphia papers (the writer frequently among them) to that high-ceilinged old laboratory in Orange, New Jersey, where after the usual ceremonies, William H. Meadowcroft, as much a part of the picture as Mr. Edison himself, would usher them into the presence of the silvery-haired old man, and then pencils would be crossed with results that each time set the world to thinking next morning.

But this year Mr. Edison was at Seminole Lodge, his Florida home at Fort Myers, and the interview was passed up, an omission which is duly covered up, one may now announce, by this interview for FORBES.

Edison’s original laboratory at Menlo Park, destined to become the source of a new light

As usual the questions and answers were written down, for the man who for more than fifty years has forged in his wonderful brain a new invention on an average of one every two weeks, whose brain has originated industries whose wealth is estimated at five times all the money in circulation, is almost stone deaf to-day, a debility which is only an affliction to others, for it allows him to think and meditate without interruption in the midst of small talk or trivial noises and is no real inconvenience to a man who is by his own rich nature a giver-out and not a taker-in. All his life Edison had taken in knowledge through his eyes, anyway, by reading, and what he gave out he gave out with his remarkable workman’s hands… “All men,” Nikola Tesla once told me, “are either centripetal or centrifugal.” … Thomas Alva Edison is centrifugal, and the ideas which have spun out from his profound inscrutable whirling center have set the world, if not on fire, at least to tingling with electricity.

“Do you believe,” I wrote, “that the age of electrical invention and discovery is over?”

Without a moment’s hesitation Edison wrote down in his decisive hand with a stubby pencil, “No; just started.”

He never seems to think. The truth is he has done more thinking along these lines than anybody else who ever lived, and the grist of all this milling thought is stored up in the bins for ready use. Edison is always thinking, that is one of the remarkable things about him. I have watched him in all sorts of places, in his laboratory, at a public dinner, when dignitaries were presenting him a Congressional Medal, and always you will see that strange expression of oblivion settle over him as he forgets himself in reflection. He can do this because he is always at ease, always original, himself, his brain poised on its own perfect bearings, independent of the flutterings and randan of the outer world.

And one remembers that framed maxim which hangs by his desk in the Orange laboratory, “There is almost nothing in the world which a man will not resort to in order to avoid the real labor of thinking.”

Edison believes that all of us think too little, a great deal below our powers. Our brains are engines, he thinks, which most of us run at only 10 or 15 per cent. efficiency. But not so with Edison: he has always driven his great engine at a hundred per cent. or at least nearer that ideal figure than any man of his time.

“Is the day of the independent inventor over?” I asked.

“No,” he replied.

“Has he been supplanted by hordes of industrial research workers? That is, has the day of private research given way to the day of corporation research work in applied science?”

“No,” said Edison.

“Well, do you think future inventions will issue from private individuals or from the great commercial laboratories?”

“Mostly from private individuals,” he wrote, “or from the exceptional man in a corporation lab.”

This was upsetting the dope, for it has been the accepted opinion for the last ten years that the day of the great individual inventor was over.

“If,” I wrote, “the work of invention should be shifting from private individuals to the great corporation laboratories, do you think incentive to invention will be weakened or lost?

“No,” said Edison. “What is wanted is a patent commission or court, all patents to be assigned to this court in trust for the inventor, the court issuing licenses always reserving a portion of the royalty for the inventor, which he cannot convey or impair.”

Edison himself underlined that in trust, and it was evident that here was a matter which he had considered deeply and felt empathically about. Here was something for Washington to think about….While I was on this line of incentive to invention, and how it might be affected by industrial changes, I gave expression to my own curiosity about Edison’s own lifelong urge for invention.

“I think there are other forms of energy not yet discovered.”

So I wrote, “Did you ever want to invent a thing because there was money in it or simply for the sake of creating new things for mankind?” And I asked furthermore whether Edison himself could have been so productive had his ideas belonged to a great corporation which fed and clothed him and removed him from all financial worry.

“I always invented,” he wrote gravely, “to obtain money to go on inventing.”

“Can you imagine any possible revolutionary discovery or invention in the offing which would upset, radically change or temporarily dislocate development of the electrical industry?”

“I cannot imagine such a discovery but it may be possible.”

“Do you think most new discoveries will lie in the radio field or in the older one of wired electricity?”

“I think wired electricity will be dominant,” he wrote, “without some great discovery not now known.”

“In your opinion will we ever have wireless transmission of electrical power?”

Late in the night Edison toiled that all mankind might have a new light

“It’s extremely doubtful,” he said, “except in a small way.”

This was interesting as coming from the man who as far back as 1883 had observed that incandescent filaments emitted particles of negative electricity, a phenomenon which came to be called “the Edison effect” and which has since become the cornerstone of radio telephony and a hundred other modern achievements.

“Without wireless power,” I asked, “do you think that aircraft can ever be electrically driven?”

“Extremely doubtful,” wrote Edison.

“Do you think all railroad mileage in America and in the world will eventually be electrified?”

“A very large proportion,” he wrote.

“Do you believe the time will come when the world petroleum supply will be exhausted and man will turn to electric vehicles?”

“If petroleum was exhausted,” wrote Edison, “we can get power for automobiles from powdered coal, benzol, alcohol.”

“Do you think man will always be able to create from Nature as much power as he will need?”

“Yes.”

“Will wind, tidal action, wave action, and earth-core-heat ever be harnessed in addition to steam and river power as at the present time?”

“Volcanic heat is already harnessed for power purposes,” he said. “Several places in Italy, one in California; tidal power in Maine and other places.”

“Do you think sunlight will ever be turned directly into electricity on a large scale for man’s use?”

“Yes,” put down Edison.

“Do you hold that electricity is the ultimate form of energy in Nature usable by man or is it conceivable that some other form may be discovered and tapped? In short, is there any imaginable form of energy beyond light, heat, radio-activity, gravitation and electricity?”

“I think,” Edison wrote deliberately, “there are other forms of energy not yet discovered.”

“Is it likely that any new way to furnish electricity will be found beyond the battery and dynamo? Can you imagine any other form of electrical generator may be hit upon in the illimitable future?”

“We may in the future get electricity direct from coal,” he wrote. “It has been done in a small way.”

“Do you think all means of storing electricity are already discovered? Perhaps this amounts to saying: Do you think your own storage battery will ever be beaten?”

“It would be extremely difficult,” he wrote, his blue eyes twinkling, “to find another chemical reaction to permit it to be beaten. But it is possible.”

And now came a wind-up question. “Comparing the electrical industry,” I wrote, “with the life of a human being, an industry which is your own child and therefore was an infant say forty years ago, at what stage of life do you think it now stands? At middle or old age?”

Edison never thought for a second but put down two pencilled words: “Yelling baby.”

And with the thought of that yelling baby in mind, of an age of whining turbo-generators, of Broadways glaring with electric dazzle and blaring with loud-speakers and storefront radios, of a thousand and one new things to speed Man on his way somewhere, one gave over sounding the mind of this great octogenarian. The fame he enjoys is well deserved. Every one who uses an electric light, watches a motion picture, listens to a phonograph, or rides over an electric railway is in part his debtor. His discoveries are at the base of industries which employ millions of men and hundreds of millions of capital. He is the central figure in an age of applied science. For many decades his country has regarded him fondly as one of the first citizens of the world.

And his country can look forward happily to having him a long time still. Eighty-two is not old for an Edison. His Dutch and Scotch ancestry has a lot of wear in it. His great-grandfather, a prosperous New York banker of Revolutionary times, lived to be 104, and his grandfather 102. His father was ninety-four when he died, and Mr. Edison says, with a chuckle, “I don’t expect to lower the family average.”

Moreover, when he touches, say, the centenary mark, he will have lived by his own reckoning to be a runner-up on Methuselah, for when he was yet a young man of sixty-five, on one of those birthday interviews, he said he had lived 115 years old. “That is,” he explained, “I have done enough to make me 115 years old, working as other men do. And I hope to keep on for twenty years more, which, figuring at the average man’s labor per day, would make me 155 years old… Then”—he chuckled—“I may learn to play bridge with the ladies.”

However seventeen of those twenty years have passed and Thomas A. Edison shows no inclination to play a rubber with the ladies. He has given up his four-hour sleep period at night, he sleeps a little more, even dozes in the day when he is tired, taking a cat-nap to save time when something is being done to his order, but he is the same hard-working, hard-thinking man he was fifty years ago. And when on one of his trips with Henry Ford became interested in an American rubber supply, and the emergency which might confront the country, and Mr. Ford shouted in his ear, “Why don’t you do something about it?” Edison chuckled, “I will, immediately,” and ever since has been Burbanking rubber out of weeds and all sorts of vegetables down on his Florida experimental farm.

His life has covered an immense lot of ground, just as his time has. Edison emerged upon the American scene just after the Civil War. As a young telegraph operator he read the works of Michael Faraday and patented his first inventions. The country was just fully measuring its resources. The trans-continental railway was being built, the first oil millionaires were appearing, Carnegie and Frick were beginning their careers in steel and coke.

The country was also just entering the new industrial era of standardized production. The war had left it a heritage of great clothing and shoe factories, of munitions factories that turned to farm implements, and of iron mills that turned to the new Bessemer process. It was just beginning to realize the potentialities of chemistry and technology.

Pittsburgh and Midvale employed the first metallurgical chemists; William Sellers did the first creditable work with tool steel; the first chemical-dye factory opened. Electricity, a toy when Tyndall made his American tour in the early seventies, became an industrial power when news came from Austria of the first dynamo.

The time was ripe for the individualist, the pioneer, on the inventive front of industry. In especial it was ripe for a genius of such versatile industry as Edison. Not merely did he have in pre-eminent degree what psychologists call the “instinct of contrivance” — the same instinct which made great inventors of the barber Arkwright, the instrument maker Watt, the school teacher Eli Whitney and the artist Morse. He had a remarkable sense for the pressure of the new industrial age; for invention depends upon industrial and social demands. He had, too, an unusual ability to build upon the general technical and scientific advance. He brought to his opportunities the method and patience of a scientist. He used his first $40,000 to build a laboratory and shop. Though he once jokingly called himself “pure practice” as contrasted with the late Dr. Steinmetz’s “pure theory,” nobody kept more thoroughly informed upon the progress of science and the “state of the art.”

Some of his inventions represent years of ceaseless, drudging experiment. To apply the electric light to general use he worked unremittingly upon dynamos, distributors, switches, feeders, fuses, meters and the other parts of the central station power system which stands as the foundation of the great electrical industry to-day. But he always remained an individualist.

The genius of this order, who jokingly describes the gift as “1 per cent. inspiration and 99 per cent. perspiration,” is rarer than a comet. He more than any other living man is the founder of the new era. It will remain for future generations to determine whether, besides fathering the new era of which they will become an elder part, Thomas Alva Edison forecast the developments of later times, of electrical power drawn straight from the sun, of the discoveries of new and unnamed energies, and of the growth of the electrical industry from a “yelling baby” to the grace and power of an unimaginable maturity.

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.