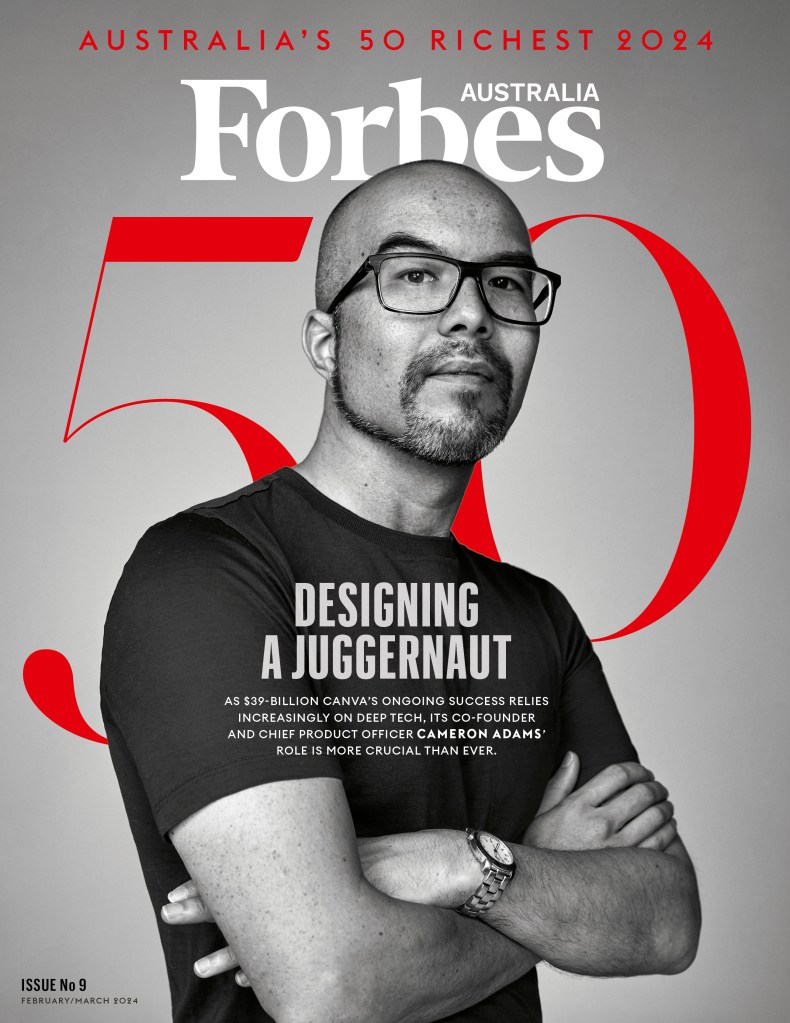

Cameron Adams was a web “rockstar” long before he co-founded Canva. Now, as the $39-billion design juggernaut’s ongoing success relies increasingly on deep tech, the third wheel in the company’s leadership trio is coming to the fore.

Issue Nine of Forbes Australia is out now. Tap here to secure your copy.

Standing in front of 3,000 people and with 1.5 million tuned in worldwide, Cameron Adams owns it up on stage in a sparkling red doubled-breasted jacket, spruiking the wonders of Canva’s 10 new AI products – more magician or game-show host than tech geek.

Getting into a lift after the March 2023 event – and before Adams, 44, takes the DJ stand for one of his techno sets at the fist-pumping staff party – an older woman of Chinese descent is marvelling at her son’s transformation. “You should have seen him when he was little. You could not get him to speak,” she says. “You would not believe it was the same boy.”

Adams’ mother, Nancy, has good reason to be astonished at her son’s transformation. Valued by Forbes at $USD2.2b in this year’s Australia’s 50 Richest, Canva’s chief product officer is Australia’s 25th richest person. While his Canva co-founders Melanie Perkins and Cliff Obrecht get most of the credit for the idea and execution of their design-democratising juggernaut, if Canva is to achieve Perkins’ goal of becoming the largest company in the world, it’s going to fall to Adams – the third wheel, the shy Chinese-Australian kid up the back of the class – to get them there.

THE LIST

There’s an oft-told story about Canva’s origins in which Melanie Perkins is pitching to Silicon Valley venture capitalist Bill Tai, who had come to Perth for West Tech Fest – and to kite surf. As she pitched, she saw him typing on his phone and presumed she’d lost him.

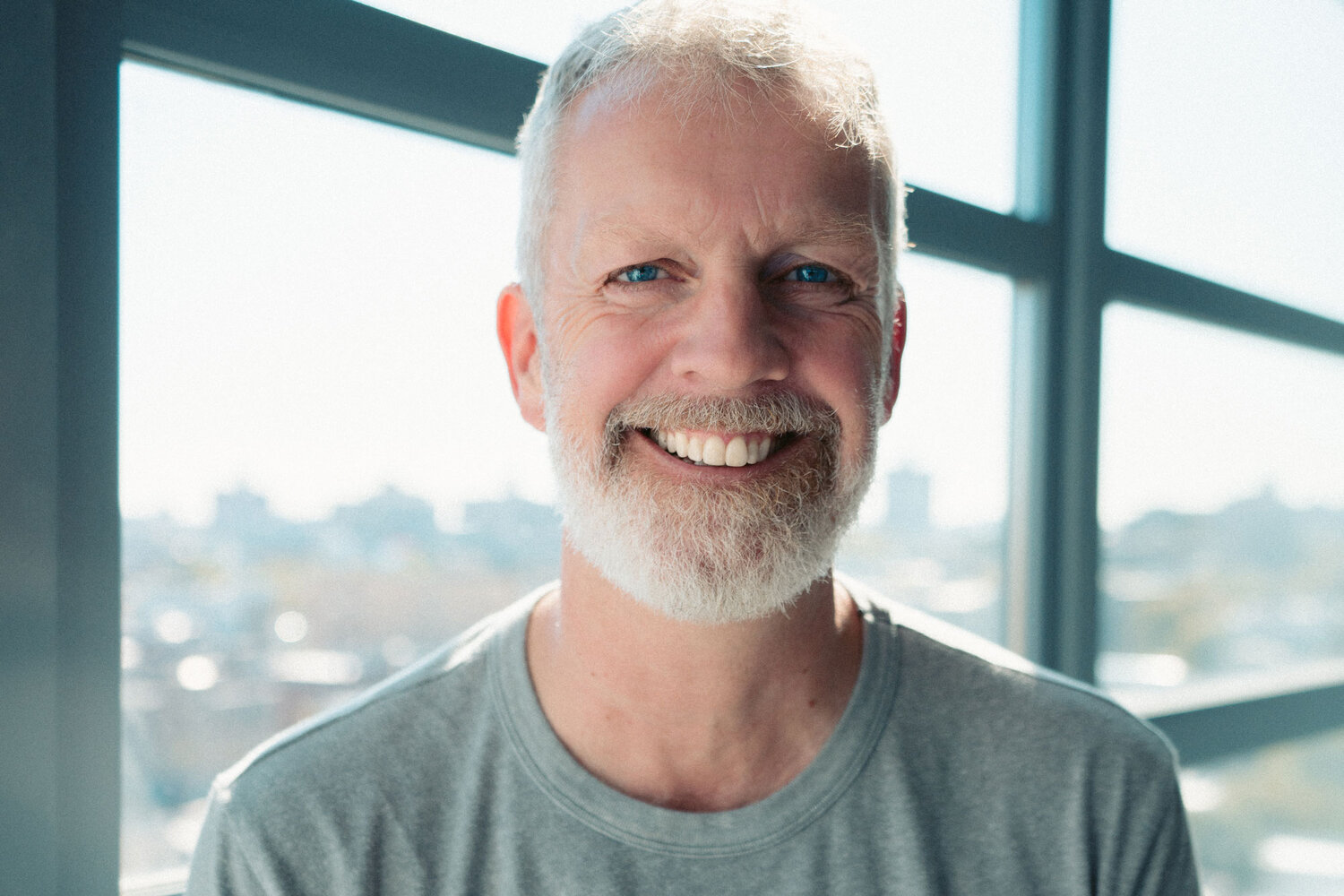

He was, in fact, messaging Google Maps co-founder Lars Rasmussen, who recalls the two-line text: “Lars, help these guys find a tech team. If you sign off on the tech team, I’ll invest in it.”

Rasmussen loved Perkins’s idea for democratising design, and for more than a year, Perkins would bring him prospective technical leads, but none scrubbed up. “I said, ‘Your mission is just too big,’” Rasmussen recalls. “‘You need the best of the best of the best if you’re going to carry this out.’

“Even back then, Melanie said, ‘We’re going to build the biggest company in the world.’ I said, ‘You mean the biggest company in design, right?’ But she replied, ‘No. the biggest company in the world.’ You need good talent for that.”

Lars Rasmussen

In the absence of a tech hire, the investment was not forthcoming, and as the months rolled on, it appeared to Rasmussen that Canva had died like so many great ideas.

And then Cameron Adams appeared.

The Man in Blue

Adams explains that going into year seven at Balwyn High School, Melbourne, he probably was the quietest kid in the class. “But by Year 12, I had complaints from my maths teacher that I talked too much.” He just found stuff he was interested in talking about.

He was good at maths and drawn towards design but never studied any design-related subjects. “My mum’s Chinese. There’s all this pressure in an Asian family to become either a doctor or a lawyer.”

He studied law and computer science at the University of Melbourne, where he picked up press-production skills on the student newspaper and started building websites and blogging under the name The Man In Blue as the 2000 dotcom bubble inflated and burst. He graduated and “totally forgot” to apply for any law jobs.

Andrew Green was a designer at Melbourne agency Eclipse who followed The Man in Blue and sent jobs Adams’s way. He remembers doing a website for Telstra where they wanted a shopping cart, which, back in 2004, wasn’t so simple. He called Adams because of his expertise in JavaScript. “You’d give him a brief at 5 pm with some animation ideas. And at 5 am, you’d get an email, and he’s got a working JavaScript prototype to show the client.” By lunchtime, he would have slept and be ready to work on any tweaks.

The blog connected Adams to designers and coders worldwide, and he got involved with the web standards scene that emerged out of the dot.com crash in the early 2000s. “It was all about pushing internet technology forward, specifying what the new tech should be, and utilising it to create new experiences.”

Maxine Sherrin was looking for “rockstar web designers” when she was founding the Web Directions conference in 2004. Adams stood out, and she got him in as a speaker. “He was the kind of person who’d stay awake until the small hours, tinkering away to get some tiny animation to work in some sophisticated way,” Sherrin says. In time, they paid him to do the opening credits for their confab – and gate crashers would sneak in just to see them, she says. “He must have spent hundreds and hundreds of hours on them. Way more than we paid him to do.”

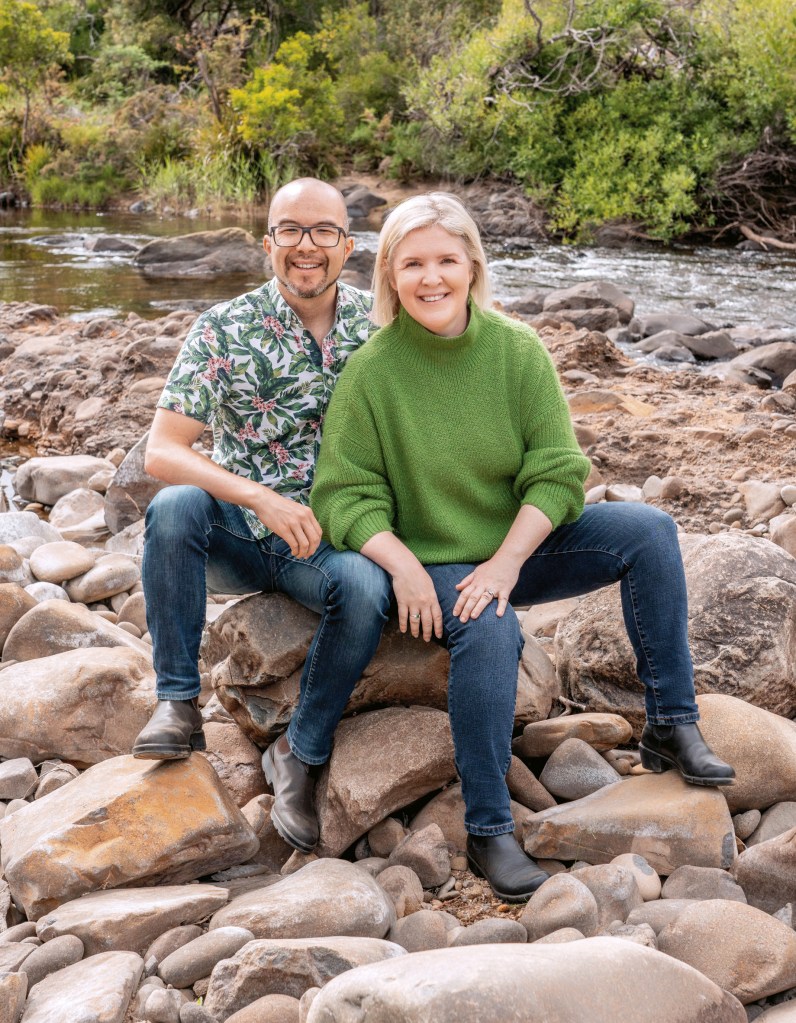

Adams started travelling the world on the speaking circuit. In 2006, he attended the South by Southwest (SXSW) conference/festival with other Australians. It was a big week. He picked up a book deal and met his future wife, Australian zoologist Lisa Miller, who had pivoted to building websites. Miller recalls that it was his creativity that first attracted her to him.

“He was ambitious but also very quiet. So, it probably took us a while to get to know each other, which was nice.”

Lisa Miller, Adams’s wife

The following year, Adams was invited back to SXSW to speak – one of the most coveted gigs in the tech world – and there was a flurry of books by him with names like The Art and Science of JavaScript.

The best of the best

Adams moved to Sydney to be with Miller, and that’s when Google Maps co-founder Lars Rasmussen heard about him. With the Sydney-founded Google Maps up and running, Rasmussen and his co-founder brother Jens had successfully pitched Google bosses Larry Page, Sergey Brin and Eric Schmidt on a new idea to redefine and reshape email and real-time messaging.

“We had a bunch of really good engineers, but we didn’t have a UI [user interface] designer,” recalls Rasmussen. He came across themaninblue.com and was blown away by Adams’s mashup of design and programming – and that he’d literally written the book on it.

Related

Rasmussen couldn’t persuade Adams to join full-time, but he did get him to do some contract work for the prototype. Six months later, when Rasmussen took that prototype to the Google bosses, Schmidt asked who did the user interface. “A contractor,” Rasmussen answered.

“Hire him full-time,” Schmidt said.

Rasmussen did. He soon had a team of 60 working on what came to be known as Google Wave.

“Normally, when you have a team that big, you have a team of ten UI designers. But we never needed another UI designer. Cameron single-handedly kept 50 engineers busy.”

Lars Rasmussen, Google Maps and Google Wave founder

Most UI designers just conceptualise something and then hand it over to the engineers to build it. But Adams would usually create the first draft himself. “By the time he handed over to the engineers, there was already an active UI that the engineers could take over and hook into the meat of the project,” Rasmussen says. “Google hires the best of the best, but even within Google, Cameron stood out. On top of that, he’s super fun to work with.”

Google Wave launched in 2010, but its half-a-million active users didn’t meet the large company’s expectations. The team was called in and told Wave was axed. Amid the heartbreak, they just stopped working.

Risk appetites

Rasmussen left for Facebook. Adams was given the freedom to go where he wanted within Google and went on a world tour of their various teams. He spent a month at Google HQ in Silicon Valley, working on the ill-fated social product Google+. “That was another fascinating insight into building a product at speed, particularly under threat,” Adams recalls. “They pulled together 400 people overnight, desperately trying to build this product to bring social media to Google and overcome Facebook. It was a bit of a clusterfuck, and I decided to not work on that one.”

In 2011, Adams and Wave engineer Dhanji Prasanna [now CTO at Block] left Google to tackle communications again with an idea to reimagine email with a start-up called Fluent.

Adams and Miller were married by this time and had a newborn. Miller had left a job at News Ltd, and they were surviving on savings, plus Google shares Adams sold, and Miller’s earnings from an online store she’d built around a dog-loving community on Facebook. The pressure was on.

“Cam and I have quite high risk appetites,” says Miller. “if everything goes poorly, we can go and get a job.’”

After nine months of bootstrapping, Fluent had a product good enough to let people start testing it. The users loved the product, says Adams, but perhaps over enamoured of the technology, the pair hadn’t considered the economics. Every new user cost them $5 a month. Buzz was being generated, however, and they soon had a waiting list of 80,000 people they couldn’t afford to bring on. They went to San Francisco looking for backers, thinking it would take a couple of days – with all their contacts and the size of their waiting list. A month later, they came home with plenty of promises but no deal. And they started prepping to go again.

Mission accomplished

From the time Lars Rasmussen had received the text from Bill Tai to find a tech lead for Canva, he’d thought Adams was the ideal candidate. However, he knew Adams was busy with his own start-up, but 18 months after receiving the challenge, the role was still vacant, and Canva was still nothing more than an idea. In March 2012, Rasmussen asked Adams if maybe he could visit this couple who’d just moved from Perth to Sydney’s Surry Hills. “They don’t have much idea about technology,” Rasmussen recalls saying. “Go and chat to them and see what’s possible.”

Perkins and Obrecht had a product, Fusion Books, built by contractors in India to make high-school yearbooks. “I walked in the door and started talking to her (Perkins),” recalls Adams. “‘Are you here for the PHP developer role?’ ‘No, I’m here to tell you how to run your business.’” She told him of the idea for Canva – to go beyond yearbooks and to make design easy for everyone. It appealed to him, but he was too busy with Fluent to give it much more thought and he got on a plane back to San Francisco for his second go at fundraising.

Rasmussen and Tai had also gone close to investing in Adams’s Fluent.

“I dug in deep,” says Tai, “but ended up passing, and others did as well.”

Rasmussen insists their passing on Fluent had nothing to do with his notion that Adams would be better placed at Canva. “I think the three founders [of Fluent] were not quite gelling.”

Soon after, Perkins, desperate now, emailed Adams in San Francisco. “Very random thought … Would you and your team be at all interested in becoming part of the founding team of Canva and integrating the beautiful technology you have developed? If we joined forces, it would make us both much stronger.”

He replied: “I’m certainly very fond of Canva and can see it doing great things, but I’m not sure my teammates would have the same passion for the area it’s going after …

“I’m certain you guys will do great things with or without us.”

Cameron Adams email to Melanie Perkins

At that time, Adams was just about to land Evan “Ev” Williams – co-founder of Blogger, Twitter and Medium, whose venture capital firm Obvious Corp had been Twitter’s lead investor. They had a term sheet ready to sign.

At the last minute, however, Williams pulled out. Demoralised, the Fluent team took acquisition meetings with DropBox and Square, but Adams wasn’t interested in returning to a large company.

“It was super stressful,” recalls Miller, “Not so much because the [investment] money wasn’t there, but when you’re a founder, you have to be nearly irrational in your belief in what you’re doing. So, when it starts to come apart and you realise you might not get there, it’s really hard to know when to stop.”

The couple started looking at jobs overseas, but Miller suggested maybe he should go back to that couple in Surry Hills. He did. Perkins and Obrecht offered him co-founder status and an approximate 20% share in the company.

Perkins says she knew Adams was the right person for the job from the very beginning:

“The incredible amount of care and attention to detail he had put into products he’d built was extraordinarily impressive and continues to be one of his many talents. While we hadn’t known each other for very long before we made the decision to become co-founders, I feel we are still so deeply aligned. From his great storytelling to his creativity, hard work, eye for design and the care he brings to everything he does, Cameron has and continues to be a fantastic partner in this amazing adventure.”

Melanie Perkins, Canva co-founder

With Adams on board, they’d also been able to entice senior Google engineer Dave Hearnden to leave his exceedingly well-paid job to join them as chief technical officer. Rasmussen went back to Bill Tai: “Challenge accepted and challenge accomplished. These guys [Hearnden and Adams] are the best of the best.” In short order, Tai invested and brought in some of his kite-surfing network, including Rick Baker from Blackbird. The first tranche was US$2 million on a US$8 million valuation, plus a matching grant from the federal government.

Bill Tai on why the design space interested him:

“In 1986 I was working for a company called Temple Barker and Sloane while at Harvard Business School – on a ‘diversification strategy’ project for a then massive company called Agfa Compugraphic that had US$500 million in cash and a dying business in phototypesetting. My project conclusion was that they should buy a startup called Adobe for $40 million. They did nothing. Adobe went on to be worth more than US$300 billion. Watching them grow over the years alongside Apple et al made me sensitised to that market and was part of the backdrop that made me open to the bright young gal, from Perth.”

When Canva was a zip file

Californian Mike Hebron – who’d been punching Fusion code for Obrecht and Perkins since meeting them in a backpacker’s hostel when they first moved to Sydney a year earlier – remembers Perkins showing him an email from Adams and noticing themaninblue.com domain. “I’d seen this guy mentioned on Hacker News. He had this really cool Daft-punk visualisation thing, and I thought, ‘Oh my goodness, I get to work with the guy who designed that!’… So tiny bit of a fanboy.”

Obrecht and Perkins had learned plenty of lessons from their yearbooks that Adams used, but Canva still had no code written. “After conversations with Mel and Cliff, he’d worked something up and came in with a zip file containing what was Canva at the time.” It had the basics of clicking and dragging an image onto a canvas and adding some text, but it needed to be hooked up to a backend so users could search for stock images and then click a button to post to Twitter or Facebook.

Hebron would recall a feeling of impostor syndrome working alongside Adams, but despite the high bar the boss always set, Adams would say, “Don’t burn yourself out,” and there was always empathy in his voice. “He’s willing to take the time to go over things that maybe I didn’t understand right away.”

After launch, there was a large screen in the Devonshire St office on which Adams had coded different metrics so they could see their progress. Hebron remembers it as a little distracting. “Wow, 1,000 sign-ups in a day!”

When asked if there was a moment he realised they’d made it, Adams says it was not seeing those 50% day-on-day growth figures but an email from a South American orphanage. “They said, ‘Thank you so much for creating this product. We use it for our newsletters to send to prospective families for the kids in our care.’ That was so humbling that there was this usage we’d never thought of which was having such impact in a place we’d never heard of.”

Magic happens

Fast forward to December 2019, and Canva has reached 97th on a list of global internet engagement, punching out 3,000 designs a minute, with 55% of them being in a language other than English. It has just raised $125 million on a valuation of $4.7 billion – bringing its total raisings at that time to $333 million.

Perkins was also on the cover of Forbes.

Canva has incorporated an AI background-removal tool made by an Austrian company, Kaleido, which has proved popular. In early 2021, Canva buys the Vienna-based company.

Canva’s head of design, Andrew Green – the same guy who’d flicked some jobs Adams’s way back in 2004 – had watched Adams bring the Vienna team into the culture but noticed how he hadn’t dived into embracing all things AI. “Cam sees the technology, but he immediately questions how this tool can be something that our users will actually use. He’s got a sceptical view of new technology. He rarely uses buzzwords or any of that kind of jargon. And I think that helps.”

But as they move into late 2022, the hype around visual AI is becoming more than buzz. They have an event scheduled to launch a suite of new features at the end of the year. And six weeks out – and three weeks before ChatGPT launched on November 30, 2022 – Canva decided to build a tool to turn written words into AI-generated images in six weeks.

Adams’s solution, perhaps informed by the Google+ mess, is to keep it simple.

“Cam still loves the idea of small teams delivering big things.”

Andrew Green, Canva head of design

The seemingly impossible six-week deadline is made doable by years of groundwork put in before, says Adams. “They had all the machine-learning infrastructure ready. We knew what models we could apply to take a text stream and turn it into an image from your imagination. We managed to click all the pieces together in that time. It got us incredibly excited for this new era of AI.”

Since then, the focus of Canva’s rollouts has been on broadening and streamlining that AI experience – from turning a 5,000-word English essay into a dot-point presentation in Tagalog or turning your hands into cat paws – the punters are voting with their mice (and Androids). In 2023, monthly users jumped more than 50% from 110 million to 170 million. They say their new AI products have been used more than 4 billion times.

On the back of that surge, they’ve increased staff numbers by 39% to 4,000 in the past 12 months, opening new campuses in Melbourne, Austin, Texas and London.

Related

And while the push for more customers in more countries with more obscure languages might be great for total numbers, the push into the corporate world will bring more paying customers. To that end, they say that 90% of US Fortune 500 companies now use Canva and that there are 135,000 corporate teams in companies with more than 1,000 employees using the app – a number they say doubled in 2023 and which Adams says will be a focus of the next decade.

“We’ve now proven that design can be democratised, and it’s something every person in the world wants and needs, which was a question that seems obvious now, but back when we were trying to look for investors, it wasn’t obvious to them.

“It’s easy in hindsight to imagine this world we’re now in, but we’ve spent the last ten years building that world, making it a reality, and getting everyone else to realise it.”

Cameron Adams

While there’s been speculation about taking the company public, two recent secondary sales of shares – the most recent of which in January reportedly valued the company at US$26 billion – have allowed early shareholders to liquidate their assets and supported the leadership’s assertion that a float is not imminent. “We’re happy staying private because it allows us to fulfil our vision. When you become a public company, there’s a lot more expectations and pressures on you that can impede innovation and growth.”

Bill Tai has never sold any of his shares in Canva, and has kept buying more, he says. He even tipped in US$5 million more when Canva raised US$200 million at its peak valuation of US$40 billion in September 2021.

Tai, founder of KiteVC, was a seed investor of Twitter and Zoom and claims involvement with the beginnings of companies whose market value now exceeds US$1 trillion.

“Start-ups are only really viable when they have great teams that can execute in synchronicity,” Tai says.

He credits Adams for his work in getting Canva out ahead of the pack in AI and setting them up to stay in front of the pack. “Canva was among the first companies out there, ever, with Open AI, in building and releasing Canva GPT, way ahead of everyone else.” Tai stresses that all three Canva founders hold equal importance: “Melanie in vision and product instinct, Cliff in operations and making the ‘machine that is Canva’ run tight, and Cameron in the core tech and product implementation. All three are fundamentally required. None are really ‘replaceable’ in a commodity way.”

Tai declined to divulge how large a stake he has in Canva. “I do not ever talk about my holdings or net worth as I actually could not tell you what I am worth as I don’t count, so don’t know …

“I have religiously stayed off any sort of net-worth list or rich list as I do not believe that is a meaningful measure of someone’s existence, and those kinds of things make it hard to raise kids and sets expectations with founders that you might be an infinite bail-out pool. It pollutes purity in thinking.”

Bill Tai, KiteVC founder

Another company in which Tai was an early investor was Blackbird Ventures. He subsequently brought Blackbird into the Canva seed round. And Blackbird has grown its stake to remain the largest shareholder in Canva, outside the founders, despite having sold down some of its holdings to realise profits for Blackbird’s early funds .

Co-founder Rick Baker said there was a “wonderful serendipity” in the coming together of the three Canva founders and their complementary talents. “There’s no doubt Cam has been instrumental to Canva’s success over the years. In the early years, he spearheaded the bringing of Mel’s product ideas to life – Mel and Cam were a phenomenal pair to lead the creation of the beautiful product that is Canva.

“Gaining a courtside seat to watch a once-in-a-generation business get crafted over a decade has been a dream come true!”

Top hustler-hacker teams

Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak – Wozniak brought the tech smarts and Jobs the vision and nous to build Apple into what is now a US$2.9 trillion company.

Larry Page Sergey Brin and Eric Schmidt – Page had the idea for Google’s algorithm, and his Stanford classmate, Brin, helped him build it. Still, investors insisted on businessman Eric Schmidt coming in to run what is now the US$1.8 trillion Alphabet.

Bill Gates and Paul Allen – While they were both computer geeks when they founded Microsoft, Allen was, at the worldly age of 22, three years older than Gates, so he tended to take on the business negotiations. He has claimed that most of their great ideas were his, and that Gates would test them and turn them into reality, and that Gates also handled sales and staffing at the company now worth $2.9 trillion business.

Issue Nine of Forbes Australia is out now. Tap here to secure your copy.