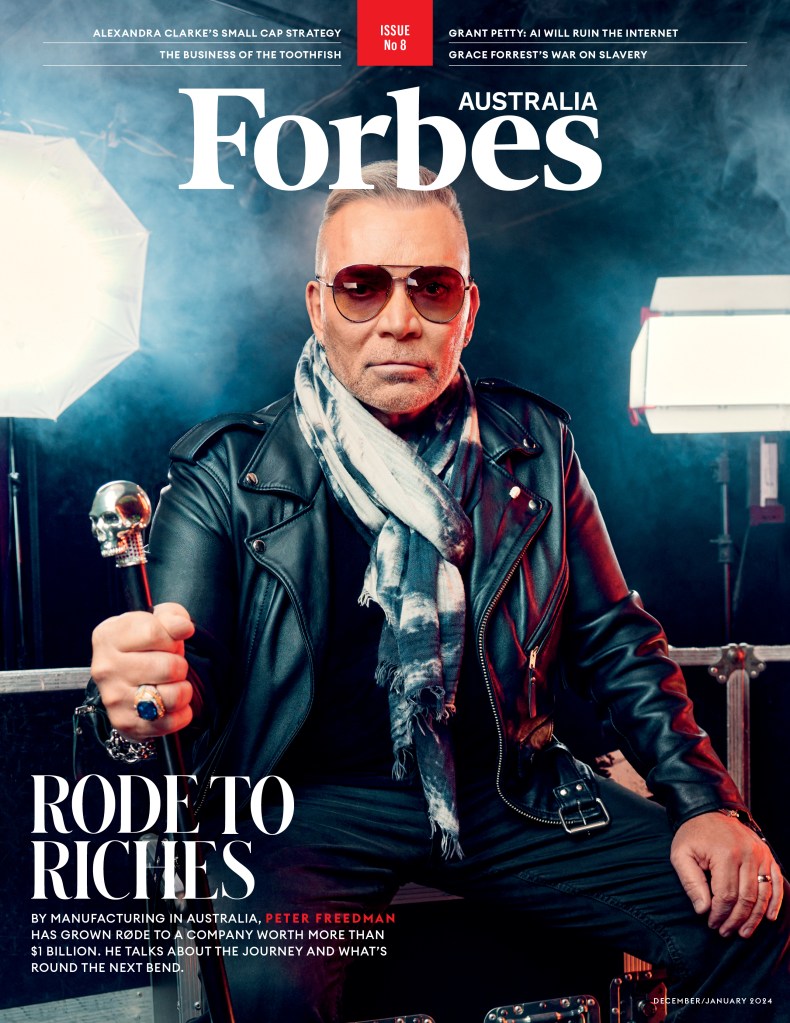

Peter Freedman, 100% owner of Rode Microphones, is promising to catapult the company started by his dad and which was almost destroyed by his youthful exuberance – to the top of the pro audio league. He’s just closed a deal worth almost $200 million to purchase US audio company Mackie, in what Freedman says is the biggest deal of his life – and he’s not finished yet.

Issue Eight of Forbes Australia is out now. Tap here to secure your copy.

Peter Freedman is running out of time. There’s so much still to do and, at 65, no time for him to build a business from the ground up like he did with Rode Microphones. He’s hinting that he’s about to buy something big enough to make an Aussie heart swell with pride, but keeping shtum on what.

Rode doesn’t do speakers?

“Watch this space,” he says, grinning. “I know speakers. I’ve designed speakers. It’s a love of mine. And there are opportunities coming up. I’d love to be involved in live sound again – what I did with my dad back in the 70s … And who knows …”

After speaking with Forbes Australia in October, Freedman jetted off around the world for a fortnight of negotiations and came back with US audio brand Mackie in his suitcase to engorge those Aussie hearts.

Freedman paid about $180 million (US$120 million) for the company, which Rode says will vault it to the status of the world’s biggest pro-audio company.

Mackie was founded in 1989, two years before Rode and similarly foresaw the home-recording boom. Where Rode dived into microphones, Mackie went for audio mixers, studio and live, before branching into loudspeakers and other gear – including mics.

Freedman says he was headed to become the world’s biggest even without Mackie, but this has sped up the process. And he’s not finished yet. There are more purchases in the pipeline.

And he’s ready to pounce. Freedman’s exact wealth is hard to verify. Rode and its parent company, Freedman Electronics, are private companies worth, he says, more than $1.5 billion. He’s come a long way for a guy who, in his early 30s, was struggling to pay the rent and put food on the table for his family.

Off a cliff

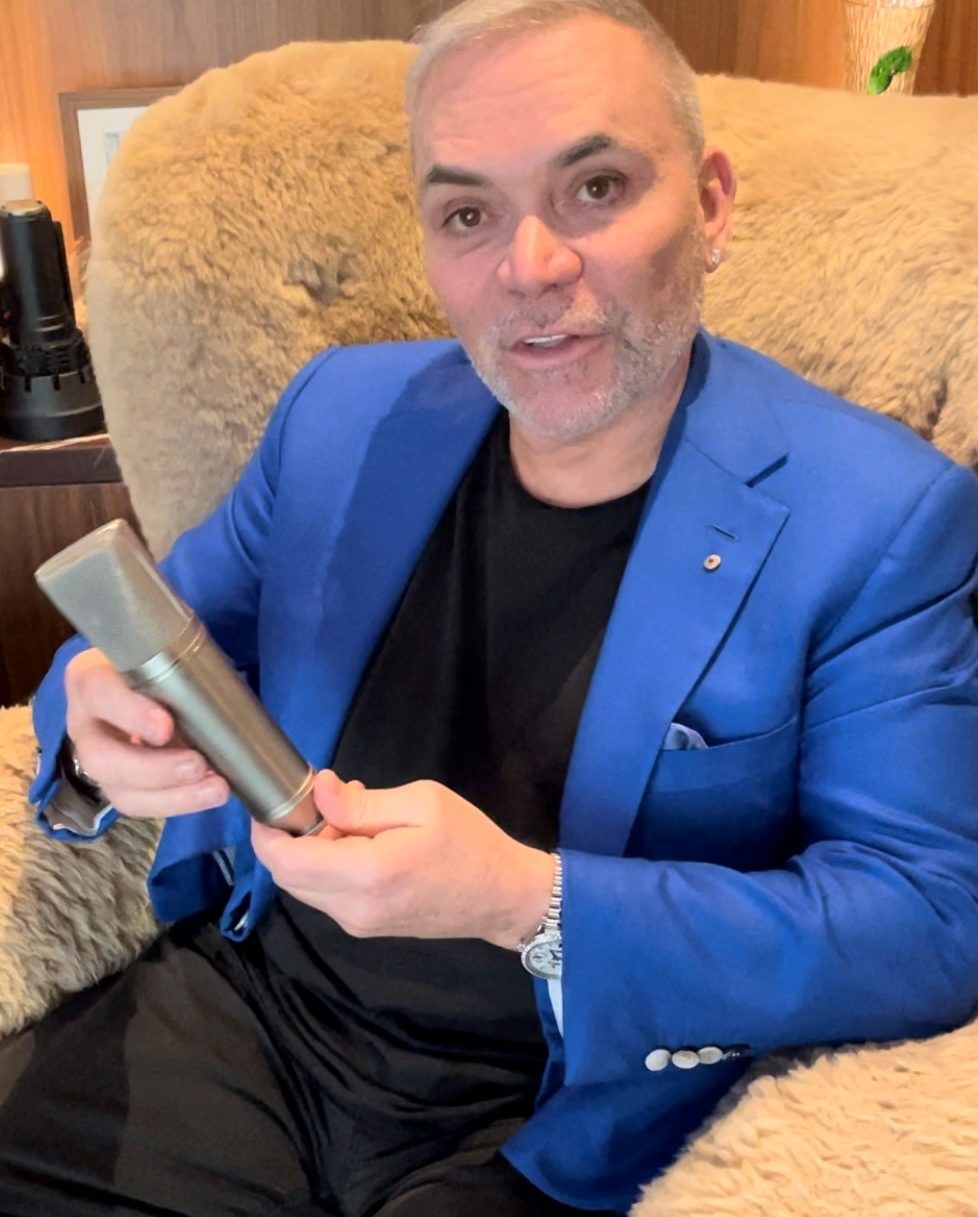

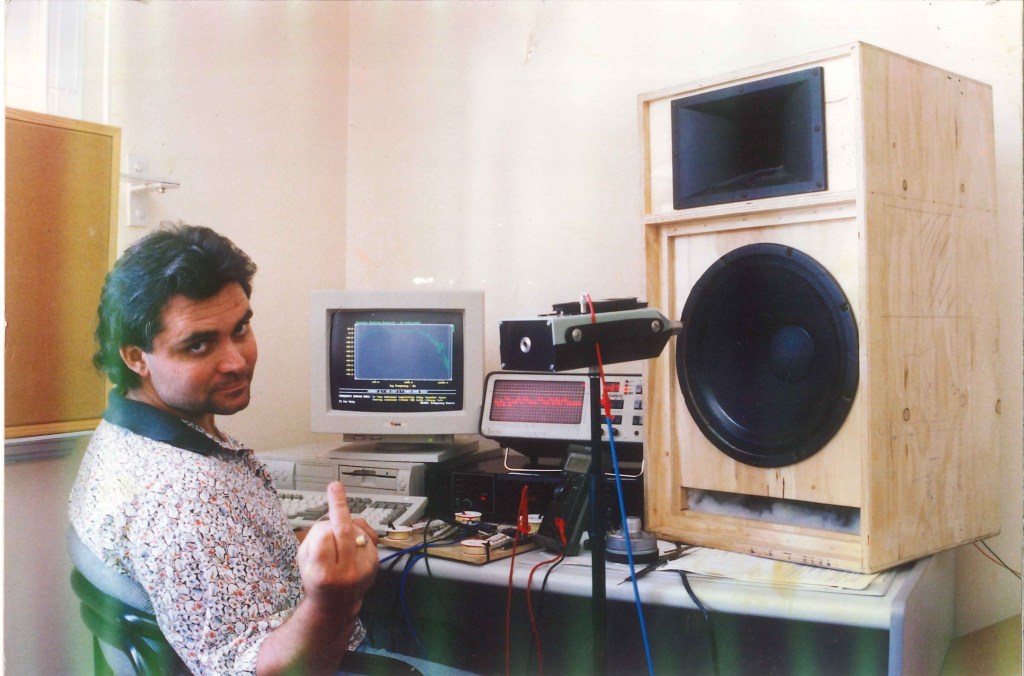

“This is the mic that started it all,” says Freedman, wearing an electric-blue sports coat, reaching behind for a metal microphone in his office bookcase. “This very one. 1981.” He was in China for a trade show just eight years after Prime Minister Gough Whitlam’s historic visit. He wasn’t allowed to even walk the streets – still full of bicycles, Mao suits and spooks. “I found this company making studio mics, and I bought it. It was my industry. I was doing live sound, bands, that sort of thing.”

Freedman’s father, English-migrant Henry, owned an electronics shop in Summer Hill, Sydney, and had the import licence for Dynacord sound systems. Peter came home with the microphone, put it in the storeroom and didn’t give it much more thought.

In 1987, right around the time of the stockmarket crash, Henry Freedman died after a long illness. Peter took over Freedman Electronics. “The late 80s was a time when everybody was going to get rich. Chris Skase was building resorts. Money, money, money. Banks were so free, starting to lend crazy money. And I always had ambition.”

Freedman took out a $400,000 loan at 15% interest and stocked up on sound and lighting gear.

Despite the crash, business boomed with the Bicentennial and World Expo 88 in Brisbane. He was installing sound for venues and selling gear to bands.

“I was young. I didn’t understand business,” he says. “We were turning over a lot of money. Things looked good. We doubled the size of the company in a year, which is, I now know, a massive warning bell.”

In 1989, everything slowed. “I’m sitting there with stock out the ying yang and a debt of 400 grand, and it just came to a crunching halt,” he says. “By the end, with interest and penalties, I owed over a million bucks.”

He sold his house, the Summer Hill shop and his car. “I had to walk to work for a couple of years. It was a nightmare. I was never going to pay it back,” he says. “I was earning a 30-grand-a-year profit, trying to pay off a million bucks with interest accumulating – wasn’t going to happen.” He tried to sell 10% of the business for $10,000, but no one would take it.

“I never went bankrupt. People have asked me why I didn’t give up. How can you give up? I was married – two little kids. I wanted to throw myself off a cliff, but you can’t. You just keep going, and you put up with eight years of hell.”

Peter Freedman, Rode founder

I was selling sound systems for less than they cost me, just so I could buy food and pay the rent. I ended up with 40 credit cards. Nightmare. But I’ll tell you, it taught me everything about business.”

In desperation, he pulled out the mic he’d picked up in China eight years earlier. He gave it to his salesman, Colin Hill, an Englishman whom he’d coaxed over to Australia in better times and who stayed when others left.

Hill took the mic to customers and came back, saying there was a lot of interest. “I think they’re going to sell as fast as a rat up a drainpipe,” Hill said. So they started calling the mic the “Rodent” and gussied up the name to “RØDE NT1”. “I came up with the idea of making it look more European with a Danish Ø,” says Freedman.

The problem with the Rodent was that it was noisy. Freedman knew enough about expensive mics to know it had a good condenser, and if he replaced the cheap Russian transistors, put in a better board and soldered them in better, he’d have a HiFi piece of kit for a few dollars’ worth of modifications.

Retailing at $500 up against $2,000-plus competitors, he sold a few hundred, then backpacked to the US on credit and jagged an order for 100. “I knew then I had something because you can’t sell anything in the US. They’ve got it all at better prices than you can buy the parts for – usually.”

After a few years, competitors started knocking on the supplier’s door. The price went up. Freedman moved to protect himself. He started thinking he could build something better for even less money. “We started making a little bit more of our own stuff. The cases, the clips. We changed the board.”

The “factory” in Rydalmere consisted of four people sitting around a table with screwdrivers and soldering irons. “We’re getting the boards and assembling them. We’re moulding bits and pieces.” It quickly became 90% Australian made, with only the transducer – the part that turns sound vibrations into an electrical signal – being imported.

“I value those times. It affected me and affected my wife. You never get over it, but I also became a much better businessman. It was school fees. The pain and the costs taught me. It’s hard and expensive.”

What lessons did he learn?

“As stupid as it sounds, if somebody had asked me before what my net profit was, I would’ve gone ‘Huh?’, he says. “I didn’t think about it. We were making money, paying our way, and I didn’t think about profit. I put a margin on everything, but was I calculating whether something was a good deal? No. I wasn’t an accountant. I am now.”

Spinning his wheels

In 1989, Freedman had been doing an installation for a new resort in the Central West NSW town of Mudgee. An enormous speaker system was meant to be hung over centre stage, which required serious engineering. “If it drops, people die,” says Freedman. In this case, the casualties would have included singer Julie Anthony and the Seekers, who were opening the place in a couple of days.

Local engineer Tony Furney recalls turning up and seeing a young bloke “doing 110mph, spinning his wheels – only smoke, no progress – and with enthusiasm to burn.” Freedman was used to such engineering jobs taking months in the city and costing a packet. Neither of which he had to spare. He told Furney the specs. Furney didn’t say much and just drove away. He came back a few hours later with his truck carrying “the best rigging I’ve ever seen”. And the price was good.

They continued to work together, and so, when Freedman wanted to expand his manufacturing, he called on Furney to make the metal casings for the mics. Furney is still making them in Mudgee. He credits Freedman with pushing him down the automation path. All on a bunch of handshakes. “He’s a very generous human being to all and sundry – which shows a person’s word equals all the paper in the world,” Furney says.

By 1997, cheap 8-track digital recording gear and personal computers were kickstarting a home-studio revolution. The most expensive part of the process was now the microphones – unless it was a $500 RØDE. The company was rising from the dead with a network of distributors in the US and the UK, selling four models. By 1999, they were out of the hole.

They won an NSW Exporter of the Year award. Freedman set a suburb record on a house in Strathfield and put a deposit on a factory in Rhodes. By 2000, he could take the family on a holiday, and he bought a robotic “pick-and-place” machine for putting electronic components on circuit boards.

“It was like I’d died and gone to heaven,” he says. “I could never have imagined I’d own one. It’s gone now. It was so small compared to what we have now.”

An obstacle to manufacturing in Australia was the lack of support industries, but that created one of the company’s great strengths. “If you’re in America or Europe,” says Freedman, “there are machining companies everywhere, there’s electronics people. You can just draw on that. Many of my competitors overseas don’t set up a factory to do it themselves because they don’t need to. Because there’s nothing here, I was forced to. Slowly, over many years, you end up with $300-million worth of gear. We could make a jet engine here. That’s the precision we have. Or a toothbrush. Anything. That’s 32 years of investment.

“Now it’s an incredible barrier to entry for anybody, anywhere in the world, to compete with me because they can’t spend that kind of money. That plating line. Did you see the plating line? There’s $30 million in there.”

In the early days, Rode’s market was musicians and home studios. “I was blown out how many people wanted to do this,” he says. “These high-end things that had ruled the world since the 1920s, they were on the way out.”

The internet, Youtubers and podcasters would fuel the next boom. “We’re more valuable than the biggest mic maker in the world. And they were the holy grail when I was a kid. $3000 mics. Who cares? Especially when I think my $200 mic is better. This handmade thing is a myth. You don’t handmake precision transducers. Imagine handmaking a mobile phone. What a joke. They sell a few hundred, and I sell a few million.”

Abundance

Peter Cooper came to work for Freedman as a design consultant in 2009, working on a mic to sit on one of those modern cameras that look like a standard SLR but which shoot high-quality video. He noted that RØDE mics looked like, well, mics. But if you wanted a mic to sit on what looked like a stills camera, there was room to rethink everything.

Cooper went on to join Rode Microphones as VP of design and new product development and says that of all the CEOs he’s ever worked with, Freedman was the most passionate about his product.

“Whatever we recommended, he would consider it and invariably say yes, whether it was a new way of doing something or spending money on a piece of equipment.

“It was a very open-minded, abundance mentality to projects and products that one doesn’t necessarily encounter elsewhere.”

Peter Cooper, former Rode designer

Cooper said the electronics and acoustics engineers would often be stuck in a problem. “Peter would put on a pair of headphones, listen to something, then make a suggestion that was invariably correct.”

Freedman admits the zeroes and ones of the technology have left him behind in recent years, but the experience he gained separating a snare from a bass at the back of a band room has left a mark. “I can hear a reverb tail that’s disappearing deep into the low end – that level of hearing helps you design stuff. It’s the goo goo juice in audio.”

Cooper and Freedman fell out in 2013 (“two stubborn people disagreeing on things”), but Freedman attributes Cooper’s influence to his current obsession with design. “Now I look at every product, and there could be 30 touch points of how we interact with it.

“The difference between it not working and being a joy to interact with is amazing. How many devices do you pick up and say, ‘This is crap?’ Think of your TV remote, think of board room conference calls.”

Peter Freedman

He recently put a million dollars into relaunching the Australian Design Council, the primary goal of which is to put Australian manufacturers in touch with designers.

“I don’t care if you’re making wheelie bins and brooms,” he says. If you get together with these designers, it’ll change your company and the systems that you do. One by one, we’ll get these people seeing it works.

“It’s incredibly powerful, and I know it works because I’ve applied it. I say to people, ‘You want to be a billionaire? Get into design.’”

Finishing the internet

Freedman handed over the day-to-day running of Rode Microphones to new CEO Damien Wilson in December 2016. But he hasn’t stepped back. When they launch a new product, Freedman will invariably scour the forums for feedback. “We do laugh at that Peter has potentially finished the internet on several occasions,” says Wilson. “And I get it. The style of owner that he is. It’s very personal for him.

Wilson accompanied Freedman on his two-week world tour deep in hush-hush acquisition talks – which, intriguingly, also took them to Asia. He says it’s hard keeping things quiet when Freedman is involved. “He’s funny. He’s irreverent. He owns the room. He is well respected within the industry. Everyone knows him. So, the worst kept secret if you’re trying to go into a business and pretend like you’re some friendlies having a meeting.

“Peter’s a futurist, you know. He’s 65 going on 40. He’s always been somehow tapped into the universe and acutely aware of all these technological trends.”

Damien Wilson, Rode CEO

“He’ll be doing the jokes, and they get it. You’re sitting in these meetings with high-end bankers. They’re just super excited to meet Peter and then go, ‘Tell me about the Kurt Cobain guitar.’ Like, What the hell?” (Freedman paid $9 million for a guitar used by the Nirvana frontman.)

Amping up

Freedman says he doesn’t discuss numbers, but … “We’re making about $100 million profit a year, and that’s growing. The company is worth a little over $1.5 billion now. And that’s growing too.”

Sales volume increased 40% during Covid, fell back afterwards, but is rising again. A simple, cheap podcast mixing desk is the new star product.

Freedman says he knocked back a $1-billion offer from private equity. He has too much left to do. “The frustrating thing for me is just time. We never sit around wondering what to make. I have enough ideas to last beyond my lifetime.” He’s looking at more acquisitions to speed diversification.

More than half the Mackie deal was financed through Sydney-based private credit firm aamica, with a debt facility that will allow for more purchases. He makes clear he intends to stay in the entertainment and home studio space, but keeps shtum on what field exactly.

You don’t do cameras?

“You never know,” he says, the grin widening. “But certainly we’re looking at cameras, at the video side.”

Will he start up anything from scratch? “It takes too long, man. I’m running out of time. I’m 65. It’s not just the cash, it’s the people, the brand and the IP. So, if there’s a company with a great bunch of people, killer brand name and great IP, but they need the power of a bigger company that has the distribution and the systems – how to manufacture, how to design, how to store parts – that’s massive. You grab a smaller company that doesn’t have all that and Swoosh! Off you go. Otherwise, it’s 20-odd years of hard slog to get there. We have huge ambitions.”

Issue Eight of Forbes Australia is out now. Tap here to secure your copy.

The Freedman Story

- 1958: Born in Stockholm to English father and Swedish mother

- 1966: Migrates to Sydney

- 1967: Father Henry starts Freedman Electronics, Summer Hill

- 1975: Leaves Trinity Grammar

- 1985: Starts Bunnies nightclub at South Sydney Juniors

- 1987: Henry dies, Peter takes $400,000 loan to expand

- 1990: Imports first cheap Chinese microphone

- 2001: Rode establishes operations in the US

- 2004: VideoMic mounted on DSLR cameras finds success with indie filmmakers

- 2006: Buys loudspeaker manufacturer Event Electronics, a company that had helped establish Rode’s US distribution

- 2015: Buys Aphex Systems whose “Aural Exciter” and “Big Bottom” audio processers were integrated into the RØDECaster Pro podcast production studio and RØDE Connect software

- 2016: Buys SoundField Limited who had first commercialised 360-degree surround sound in the 1970s

- 2018: Releases “world’s first dedicated podcasting console”, RØDECaster Pro

- 2023 Buys Mackie.

The Mackie Story

- 1989: Founded as Mackie Designs by Greg Mackie in his Washington State condo. Sensing the rise of the home-audio movement, Mackie had already started and sold two audio companies.

- 1991: Moves to a factory and releases second audio mixer, the CR-1604.

- 1995: Becomes a public company, sells its 100,000th mixer and moves into a bigger factory.

- 1996: Diversifies into amps and studio-quality speakers.

- 1998-2001: Employing almost 1,000 people, buys loudspeaker maker Radio Cine Forniture (RCF), sound reinforcement system manufacturer Eastern Acoustic Works (EAW), Sydec and Acuma Labs.

- 2003: Greg Mackie steps down and sells his controlling interest. The buyers rename the company Loud Technologies but keep the Mackie brand. They divest Italian operations, including RCF.

- 2005: Loud buys sound brands Ampeg, Crate Amplifiers and Alvarez Guitars.

- 2007: Buys Martin Audio.[24]

- 2017: LA-based private equity firm Transom Capital buys all brands owned by Loud Technologies, including Mackie whose manufacturing has moved to China.

- 2018: Loud divests all its audio assets except the Mackie brand which continues as a market leader in studio recording, mixing, microphones, headphones, podcasting tools, amplification and processing.

- 2023: Bought by Rode for $180 million (US$120 million).