Two Melbourne engineers turned undergrad frugality into a superpower, leveraging their Forbes Australia 30 Under 30 listing into a space up and comer.

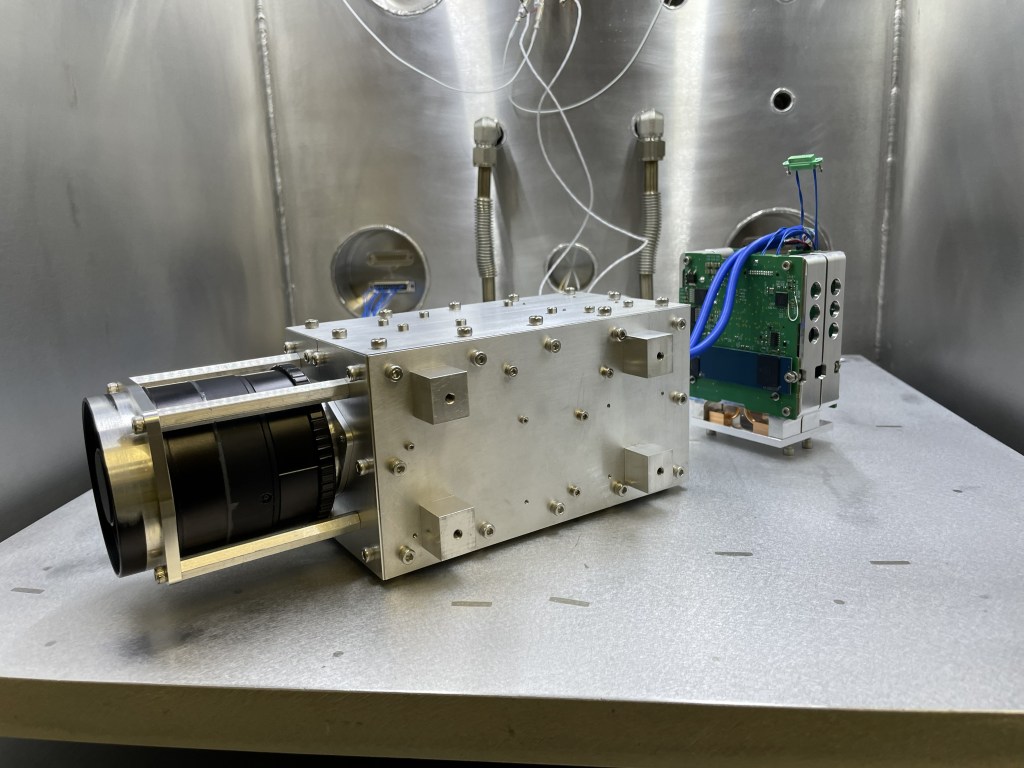

At an age when most engineering grads are still polishing their LinkedIn pages, Shoaib Iqbal, 25, and Przemyslaw “Joey” Lorenczak, 28, have put four hyperspectral sensors into orbit for less than the price of a Melbourne house.

Soon after appearing in Forbes Australia’s inaugural 30 Under 30 last year, Iqbal and Lorenczak raised a $5.6 million seed round – jointly led by Darwin’s Paspalis Capital and Melbourne-based Islamic financial services company Hejaz – to fuel their bolder ambition of having a constellation of 18 satellites in space by the time they turn 30.

The duo started Esper when they were in second year at Monash University.

Undergrad frugality is the reason they got into space for under $1 million, says Iqbal. “That’s where we get our big edge,” he says.

They couldn’t afford any parts other than COTS – “commercial off-the-shelf”. “We had the philosophy of using COTS components that you could get at JB Hi-Fi and engineer them to survive in space. We built a lot of unique intellectual property in-house to do that … and that’s what allows us to keep our manufacturing costs so low.

“And then we also just like to hustle and negotiate down the launch costs with our providers and whatnot to get the cheapest rate out there.”

Iqbal, who grew up in Saudi Arabia, was studying mechatronics, and Lorenczak, who grew up in Poland, mechanical engineering, when they met during first-year at Monash in 2018.

Iqbal then jumped over to RMIT to specialise in space science. That shift, plus a shared obsession with SpaceX, Rocket Lab and the broader boom in commercial space, planted the seed to build something of their own.

In 2019 they entered UniHack Melbourne, then the city’s biggest hackathon, with an idea for an algorithm that could design new satellite subsystems. They won. And they took it as a sign. Maybe this wasn’t just a uni project. Maybe it was a company.

But six months of hustle brought them back to earth. “No one wanted to buy it,” Iqbal says.

Then the east coast of Australia caught fire. As the Black Summer bushfires of 2019-20 raged, Iqbal and Lorenczak saw a problem worth solving. Why not pivot to environmental sensing from space?

They explored smoke detection, thermal imaging, even whether they could cannibalise a whole smartphone, rebuild it and fly it in orbit. Then a uni advisor pointed them to hyperspectral imaging – a technology they’d barely heard of. But the more they dug, the more it looked like a Swiss Army knife: useful not just for disaster response but agriculture, mining, defence, insurance, infrastructure.

Iqbal calls it “a self-taught PhD”: reading papers, recreating results, building crude prototypes between undergrad classes. Back then, hyperspectral in orbit was mostly theoretical — a couple of missions flown, plenty more promised.

Hyperspectral imaging, Iqbal says, works because it sees the world in far more colours than the human eye — or the satellites that have gone before. A standard satellite camera captures three bands of light: red, green and blue. Even the more advanced multispectral sensors top out at maybe 10 or 20 bands. “That really limits the amount of spectral information you get,” he says.

Hyperspectral, by contrast, breaks the spectrum into hundreds of narrow bands. Every material on Earth – soil, minerals, vegetation, even atmospheric gases – absorbs and reflects light in its own distinct pattern. With hundreds of data points to analyse, those patterns become an optical fingerprint.

“We want them to pay themselves off because that justifies why they need to exist.”

Shoaib Iqbal, Esper cofounder

“It basically becomes a chemical sensor,” Iqbal says. That’s why the same instrument can detect nitrogen levels in a wheat paddock, methane leaking from a pipeline or a ridge of stressed vegetation primed for a bushfire.

They tested the concept with a hyperspectral sensor bolted to a drone and flew it over a vineyard, mapping the spectral difference between healthy and struggling vines. The results were good. It convinced them to go ahead and build a version for orbit.

Mineral exploration is one of the biggest use-cases so far. From space, they can read the surface clues that hint at what lies underground — the chemical signature of certain soils, the moisture they hold, the vegetation they support. Even when the mineralisation is buried, those surface proxies can point the way.

“Most of our customers might have a hundred square kilometres to investigate,” Iqbal says. “Only one square kilometre is worth anything. We help them find that one.”

And at $1.50 per square kilometre, it beats throwing a swag in the LandCruiser.

A World Economic Forum study conducted by Deloitte found huge benefits will flow from earth observation technologies. “By 2030, the economic opportunity afforded by Earth observation insights is projected to surpass US$700 billion while directly contributing to the abatement of 2 gigatonnes of greenhouse gases annually,” the report says.

Esper’s first satellite, Over The Rainbow, went up in March 2024 aboard SpaceX’s Transporter-10 mission and had proved that it worked by the time Forbes Australia’s inaugural 30 Under 30 list came out seven months later.

“It gave us credibility and visibility,” says Iqbal. “It opened doors we wouldn’t have had otherwise.”

Capital raising accelerated in parallel. Only months after landing on the under-30 list, they closed a $5.6 million seed round.

Since then, Esper has added three more assets in space: two “virtual missions,” where they purchased capacity on third-party satellites, and, three months ago, they launched a second piece of Esper-built hardware – Esperesso, the size of a toaster – now circling the Earth.

All of it is leading to what they call the “flagship generation” – a fleet of microwave-oven sized workhorses to scale their ability to scan the entire planet and deliver data to thousands of potential clients. The first of those is due for launch in June 2026, after which three more will be launched by the end of 2027, by which time they project they’ll hit profitability.

But a lot more capital needs to be raised before they reach their goal of an 18-strong constellation in orbit by 2029.

“It’s a high capex business, but the return on that investment is very quick because of the impact that we have with our customers. We’ve designed our assets to be profitable within six months of operation.

“We’ve engineered our unit economics, our pricing … to make sure that as soon as we get our assets up there, we want them to be almost instantaneously profitable. We want them to pay themselves off because that justifies why they need to exist.”

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.