The Australian story behind PsiQuantum, the Silicon Valley unicorn that received almost $1 billion of taxpayer money to build a quantum computer in Brisbane.

This story featured in Issue 12 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

Professor Andrew White could tell his postdoc student had itchy feet. It was 2004, and they’d just become the first in the world to demonstrate an “unambiguously entangled quantum logic gate” – the first step in building a quantum computer. It was published in Nature, the first step for the student, Jeremy O’Brien, to build a stellar scientific career. The professor knew he had no budget to keep O’Brien at the University of Queensland, so he threw a job ad for a junior academic role in the UK onto O’Brien’s desk.

White got on the phone to the senior professor at Bristol: “I’ve got this great young bloke called Jeremy. I’ll just warn you though, in two years from now, you’ll be working for him.”

The professor laughed, White recalls, adding that he caught up with that professor three years later at a conference. “You did warn me,” the Brit laughed again. Because O’Brien was building a quantum empire at Bristol that would grow to 100 people, all working on how to build a quantum computer – then more an ethereal concept drifting between science-fiction and psychedelia in its promise of changing the world with incomprehensible computational power.

“We used to joke that people drove lorries full of money and just backed them into Jeremy’s lab,” says another of O’Brien’s former colleagues, Andrew Doherty, now a professor at the University of Sydney, but who recently spent a three-year sabbatical working for O’Brien.

O’Brien’s team’s work at Bristol was, in 2016, spun into Silicon Valley start-up PsiQuantum, into which private investors have backed up another US$665 million, valuing the company at US$3.15 billion in July 2023. But PsiQuantum got a lot more valuable this April when O’Brien convinced the Australian and Queensland governments to agree to back their lorries loaded with AUD$940 million [US$250 million in equity split between the governments and the rest in loans] into PsiQuantum’s docks, for them to build a quantum computer in Brisbane.

The governments were accused of running a sham selection process and, indeed, of “picking winners”.

Then it was announced on July 25 that he’d convinced the Illinois government to tip in US$500 million of tax incentives for PsiQuantum to build their second computer in Chicago. And while that might sound like a discount on what Australia paid, O’Brien got Illinois to offload another US$200 million to build a cryogenic plant to his specifications.

The goal is to build the world’s first useful quantum computer in Brisbane by 2027, and Chicago by 2028 – and to build them before the likes of Intel, IBM, Microsoft, Amazon, the Chinese government and a peloton of start-ups can build theirs. Whoever gets there first will be able to charge a bomb for time on their machine because such devices are predicted to be able to do things current computers can’t – from complex drug design and streamlining city traffic flows to breezing through existing computer encryption, smashing the blockchain and creating artificial intelligence more akin to a human brain.

Such a machine would bring $5.1 billion in direct economic impact to Queensland and Australia, creating 2,800 jobs by 2032, according to a report by the Mandala Group, commissioned by PsiQuantum. What it might bring to PsiQuantum, they’re not saying.

So how did this Silicon Valley start-up with roots deep in Australian and British academia come to be about to pour concrete next to Brisbane Airport to start building this machine?

The Slog

Mad-professor hair notwithstanding, PsiQuantum’s four founders seem charming and normal. They converse with warmth and humour and do not comply with the stereotype of geniuses surrendering real-world smarts to make way for enormous processing power.

Jeremy O’Brien, on a Zoom call from Warrington in the UK, traces his quantum computing journey back to 1995 when he was a 19-year-old physics undergraduate at the University of Western Australia and picked up a year-old copy of New Scientist. “It described how quantum mechanics is not only whacky, weird and wonderful, but how you could do something incredibly useful if you could get it under control and build a quantum computer. And I’ve been pretty well hooked ever since,” he says.

“He’s a force of nature and very charismatic, but he just doesn’t take no for an answer and barrels through things. He doesn’t have the same inhibitions as the rest of us.”

PsiQuantum co-founder Terry Rudolph on Jeremy O’Brien

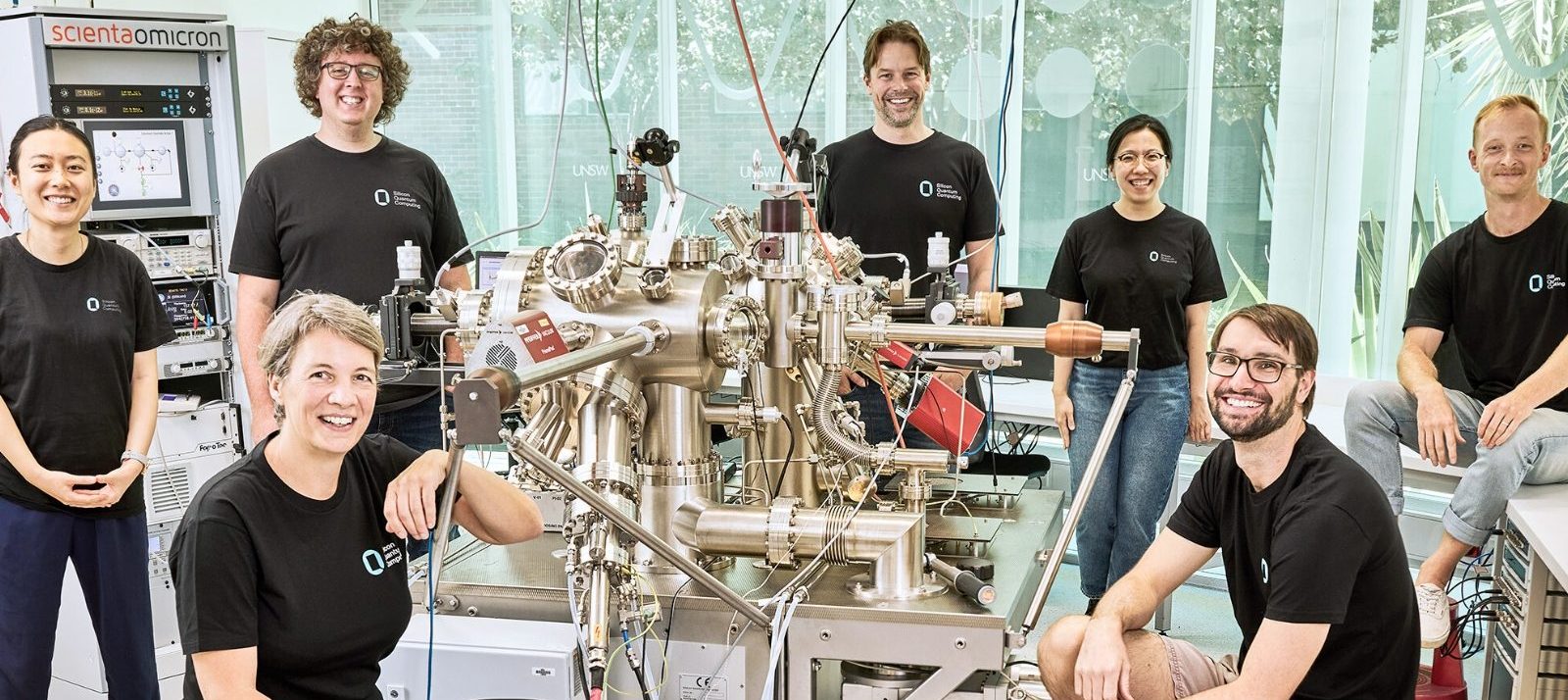

O’Brien moved to Sydney’s University of New South Wales to do a PhD. “It might have been the only place in the world that you could do a PhD in building a quantum computer,” he says. One of his supervisors, Bruce Kane, had come up with the idea for making a quantum computer using single phosphorus atoms in a silicon chip [the idea that has inspired two UNSW spinouts, Michelle Simmons’ Silicon Quantum Computing and Andrew Dzurak’s Diraq]. Another postdoc there at the time was David Reilly, who, until July, ran Microsoft’s quantum team at Sydney University.

O’Brien spent the next five years working on that idea but had “a bit of a crisis”. “I just couldn’t see a way that we could scale things up to the million qubits [quantum bits] needed to actually bring about this profound impact of the technology”.

But that’s when Gerard Milburn at the University of Queensland, with colleagues at Los Alamos in the US, figured out a way to use light particles, photons, as qubits. “I managed to talk my way into a postdoc at the University of Queensland with Andrew White, who was setting up a lab to try and pursue this photonic approach – despite me not knowing which end of the laser light came out of.”

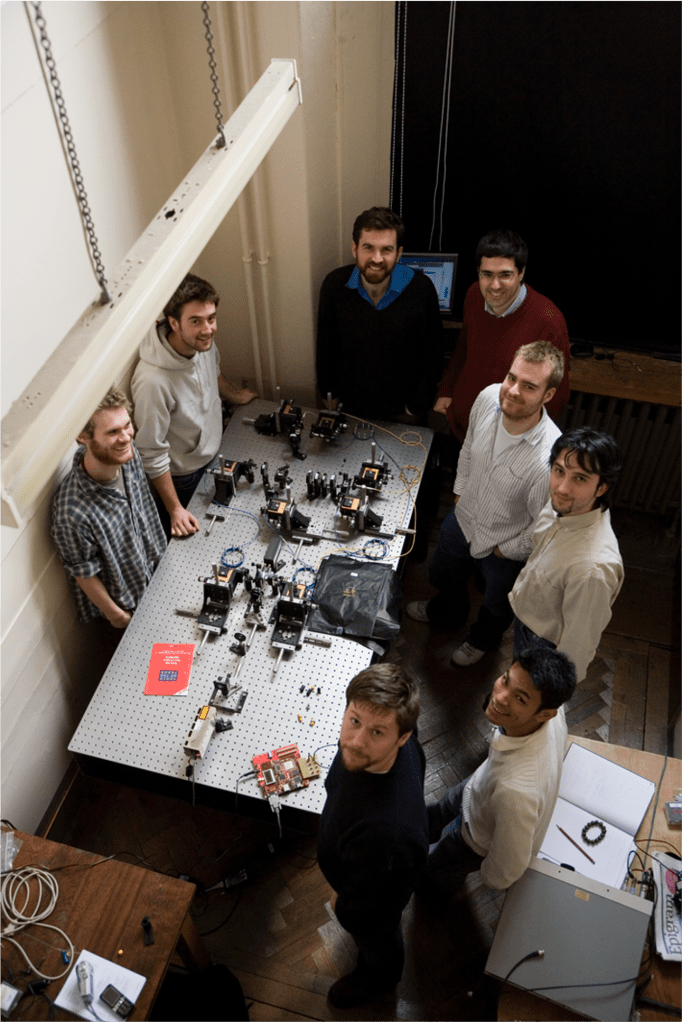

O’Brien teamed up with another postdoc, Geoff Pryde. “It was clear from the beginning that Geoff and Jeremy were engines,” says White. “They were just very good physicists, very driven.” That partnership led to the 2003 Nature paper, where they achieved “quantum entanglement” using mirrors and beam splitters bolted to a three-metre bench.

O’Brien wrote his own press release. “Twenty-something years ago, that was not common for physicists,” says White. They all got interviewed about it. “Jeremy drove that. He always knew the importance of communicating the science.”

They had created a quantum logic gate, the building block of a quantum computer. However, the problem remained of how to turn that enormous transistor into a million-qubit quantum computer. Coming from the UNSW world of silicon quantum, O’Brien wondered if you could combine silicon with UQ’s optical approach to shrink it all down. He knew he needed three prongs – somebody who understood quantum, somebody who could design a chip, and somebody who could make that chip.

And that’s when White threw the job ad for Bristol’s Centre of Quantum Photonics on his desk. “I applied on the same day,” says O’Brien. Bristol had the ability to manufacture the components he needed to bring the dream to life. Britain also had systems designed to move fast. He fondly recalls getting a $250-million laser with a one-page application. He also got grants to employ a lot of people.

Optical engineer Mark Thompson cold-called O’Brien to ask if it was even worth his while applying for a senior job in O’Brien’s new team at Bristol. Thompson, a physics graduate, knew nothing about quantum, but he’d had a career in the optics industry and at Cambridge, where he’d been contemplating a career in academia – “eating at the high table” – until itchy feet got him looking at what would be the next big thing in photonics. He landed on Bristol’s quantum work.

O’Brien told Thompson he should, by all means, apply – even though Thompson was about to go to Japan for an 18-month secondment to Toshiba’s silicon photonics research centre. All the better.

“Not a lot of academics would have seen that opportunity,” says Thompson. “They all say they need you now for lectures and writing research grants. But Jeremy always had the long view – he knew the skill sets he needed to [build a quantum computer].

Thompson watched how Japan’s “massive industrial machine” worked and how they could use that at the university. “A year and a half later, I was back in Bristol with this amazing partnership under my belt. We ran with this idea of taking quantum physics and quantum optics and merging them with photonic engineering to create this whole new field.” Thompson thinks they coined the job description “quantum engineer”.

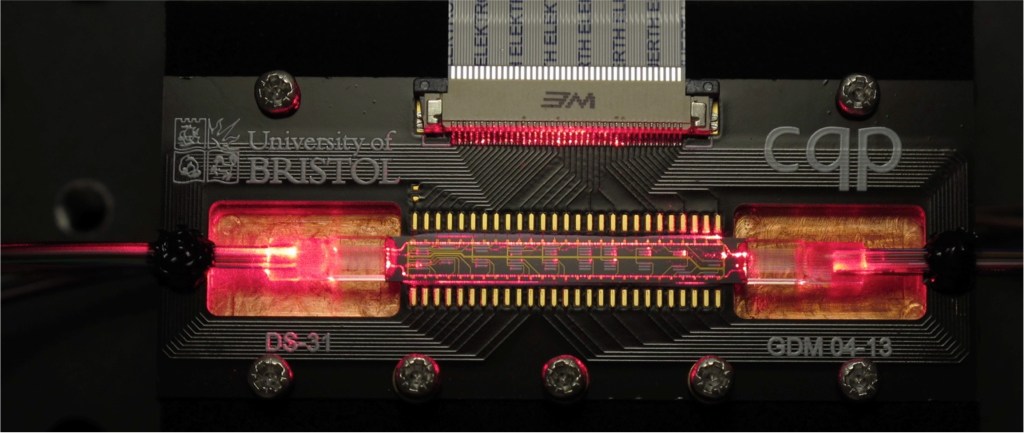

Five years after the first Nature paper, O’Brien’s team got another article in the esteemed publication, taking everything they’d done on a 3-metre, 1-tonne bench at UQ, and doing it in a silicon chip.

All in the Family

Terry Rudolph grew up in landlocked Malawi, south-eastern Africa, the son of teachers. He’d only tasted chocolate once before the family migrated to Queensland, in 1985, when he was 12. Brisbane seemed alien with its traffic and trains.

He studied physics and maths at the UQ before going off backpacking. It was only then that he learned his grandfather was Erwin Schrodinger, the Nobel Prize-winning Austrian physicist who coined the expression “quantum entanglement” in the 1930s and is best known for his Schrodinger’s Cat thought experiment, which attempted to explain that the way an electron behaved depended on whether or not someone was observing it. This fundamental notion of quantum physics disturbed Albert Einstein, causing the two men to remain at intellectual loggerheads for the rest of their lives. Experiments later proved Schrodinger correct.

Rudolph learned about his famous grandfather only after he’d decided his future lay in physics. “I had already published my first academic paper,” he says. “So it didn’t make me second guess myself. I already knew this is what I was going to do.”

In 1995, Rudolph’s backpacking took him to Toronto, Canada, where he started a PhD in quantum optics – the year that the notion of quantum computing took off and O’Brien read the New Scientist article. “If you’re an early mover in a field,” says Rudolph, “you don’t have to be as good because there are not as many people in it, and there’s lower-hanging fruit to pick.”

“He was thinking about flying off on a cloud and becoming a god of physics, smoking his pipe the rest of his life.”

PsiQuantum co-founder Pete Shadbolt on Terry Rudolph

That low-hanging fruit got him a postdoc in Vienna with Anton Zeilinger, who won the 2022 Nobel Prize for physics. “He was very supportive even though I’m a theoretician, and he was an experimentalist.” That practical knowledge got Rudolph to Bell Labs, the research company that had spawned such things as radio astronomy, transistors and photovoltaic cells. He worked with Lov Grover, who, in 1996, had come up with quantum computing’s second foundational formula, Grover’s Algorithm. “He had some funding – he just said, ‘I’m gonna hire you for a couple of years, like a consultant, to teach me about the practicalities of quantum computing.’”

Rudolph took a pay cut to return to academia, moving to Imperial College, London, in 2003, around the same time O’Brien moved to Bristol. They had got to know each other on the conference circuit and in Rudolph’s visits back to Queensland during the northern winter.

At first, they caught up socially more than collaboratively. Rudolph kept publishing seminal papers in the quantum sciences, but peripatetically, and O’Brien kept trying to focus his brilliant friend’s attention on what a quantum computer might look like.

Professor Andrew Doherty met them both at this time, and they both seemed “very Australian” to the Kiwi professor – brash, outgoing and charismatic in a way physicists usually weren’t. “They’re compelling personalities. They’re a lot of fun to be around.” He’d talk literature with O’Brien – unusual in the physics world – and Rudolph, well… “If you’re going to talk to him about physics, you’re going to have a huge argument. He’s passionate about it. Super smart.”

Rudolph did start looking at how a quantum computer might use light. “Photons are just a very different way of encoding your quantum information,” he says. “Light is never stopped. It’s always running around. It’s moving fast, so it has things that make it problematic, but then it has things that make it a beautiful way of doing quantum computing.”

“I lived through this thing that you see in the Silicon Valley TV show. Where you flip from ‘Geez, could I just meet any investor this month?’ to suddenly, they’re all calling you.”

Jeremy O”Brien

In 2005, Rudolph published a paper, Experimental One-Way Quantum Computing, in Nature. “But it was still not practical,” he says. “I found it intellectually interesting, but I wouldn’t have put money on it being a reasonable way to go.”

Over time, Rudolph started to get to know people in O’Brien’s group. “He was building an empire, an amazingly large group,” recalls Rudolph. “He’s a force of nature and very charismatic, but he just doesn’t take no for an answer and barrels through things. He doesn’t have the same inhibitions as the rest of us. He wanted the young people on his team to be empowered. So he wasn’t micromanaging. He was bringing in good people and giving them the resources to do things.”

One such young person was Pete Shadbolt.

As a kid, Shadbolt had always wanted a Nintendo. “My Mum and Dad were hippies. They got me a 486 PC and a family friend gave us a copy of Turbo Pascal, a very early programming language, and they said, ‘Write your own bloody video games.’”

By 17, he’d created Free Rider, a game that’s gone on to have a billion downloads. He’s visibly embarrassed to even own up to it now. He turned up at Bristol to do his PhD under O’Brien. “I was just so lucky to come right at the beginning of what Jeremy was doing. It was a really simple idea: take these silicon chips from the telecom industry and repurpose them – put a single photon in there instead of a bright laser pulse.”

After his PhD in experimental quantum with O’Brien, Shadbolt went to London to do his postdoc in theoretical quantum with Rudolph – aiming to work out if building one of these computers was possible. Shadbolt, as the interloper experimentalist, saw it as his role to cop a bit of stick from the theorists when he’d ask silly questions. But he’d roll his eyes right back at those head-in-the-clouds theorists when they started talking about making anything.

Shadbolt became the “glue” between the experimentalists like O’Brien and Thompson and the theorists, says Rudolph.

Shadbolt could see Rudolph eyeing bigger goals – “foundational stuff, Nobel prize kind of stuff”. Like PBR (Pusey-Barrett-Rudolph) theorem [one of Rudolph’s earlier papers]. I don’t understand it either, but that was a huge result in his career, where he was thinking about flying off on a cloud and becoming a god of physics, smoking his pipe the rest of his life.”

Silicon photonics – the ability to switch light in silicon chips – was catching up to the point where they could plausibly make a small quantum computer. But they needed millions, ideally billions, of these switches. Another of Rudolph’s PhD students, Mercedes Gimeno-Segovia, was also trying to figure out how to do it. Rudolph doubted she could get there.

Gimeno-Segovia had seen what the crew at Bristol were doing and was convinced they would build a quantum computer. She tried to get Rudolph enthused, but he remained sceptical. She, however, was stubborn, explains Shadbolt. “And he said, ‘Fine, if you can show this particular elusive property of these architectures, then we’ll take you seriously, and we can get on with maybe doing this.’”

“He and I believe quantum computing is probably the most important technology since fire.”

Playground Global co-founder Peter Barrett

Gimeno-Segovia and Shadbolt succeeded in 2014. “That [paper] was the foundation for PsiQuantum,” says O’Brien. “We had this architecture that we believed satisfied what I had been trying to do all the way along, like back in the Sydney days: How do we leverage the semiconductor industry to make a quantum computer.”

There were still open questions, says Shadbolt, but it gave them the conviction. “We better stop going to conferences, stop writing papers, stop messing about and really try to build this.”

Yea though I walk through the Valley

O’Brien wangled a year’s sabbatical at Stanford and immediately turned his attention to finding investors. But with no network and no connections, he flailed. It was not until a year later, in January 2016, that he found himself at the World Economic Forum in Davos, where he met Dileep George – an AI and robotics researcher who was cofounder of Vicarious, a project funded by internet billionaires Peter Thiel and Dustin Moskovitz. George made a “whole bunch of introductions”, and O’Brien was away.

“I lived through this thing that you see in the Silicon Valley TV show,” says O’Brien. “Where you flip from ‘Geez, could I just meet any investor this month?’ to suddenly, they’re all calling you.” Aside from the scientific know-how, he was armed with consultancy estimates talking about trillions of dollars of value that could be created if this quantum thing were to happen. So, he had their attention. One investor called him nightly, right when he’d be trying to get the five-year-old to sleep.

Crucially, he met Jeff Brody from Redpoint Ventures, who put him on to Peter Barrett at the newly-started fund, Playground. Barrett was an Australian who’d dropped out of Sydney Uni in 1986 to join a US start-up. He’d given Elon Musk his first job in Silicon Valley at game company Rocket Science and had spent time with Bill Gates in 13 years at Microsoft.

“Jeremy and the team at PsiQuantum are the smartest people I’ve ever worked with – no, seriously. I mean, Bill and Elon are geniuses, but it’s not just Jeremy.”

Playground Global co-founder Peter Barrett

Barrett felt he had a sense of the traits that made a successful founder. “Jeremy had all of the characteristics I look for in that he was a deep domain expert. He understood how to build a quantum computer better than anybody on earth. He was driven and willing to say, ’Look, if I had to build the machine today, it would be a million times too big. But let me tell you how we get there.’ He wanted to translate his life’s work into something important. He and I believe quantum computing is probably the most important technology since fire. You need people that just want it really, really badly because it’s hard, and people are going to kick you in the shins, and it’s going to be brutal, and it’s going to be a long grind, and if you don’t care about it – not gonna happen.”

Barrett knows what he’s talking about. Playground has now backed 10 unicorns at their seed or Series A funding rounds and remains the largest shareholder in most of them. He says the other big thing going for O’Brien was the people he’d gathered around him.

“Jeremy and the team at PsiQuantum are the smartest people I’ve ever worked with – no, seriously. I mean, Bill and Elon are geniuses, but it’s not just Jeremy. You’ve got Terry Rudolph, Pete Shadbolt, and Naomi Nickerson who designed the architecture. That company is ridiculous in terms of intellectual horsepower. Every time I interact with them, I learn something. They are just the most multi-disciplinary team of geniuses.”

O’Brien shook hands with Barrett and Brody in April 2016, raising US$13 million to begin the long grind. PsiQuantum was born.

O’Brien, Thompson and Shadbolt were all in as founders, but Rudolph was still sceptical. “I wasn’t going to be a founder at first. I was quite happy in academia. I didn’t need the headache.” O’Brien, however, was not good with ‘Nos’ and kept at him. Rudolph uses the word “bulldozer”. He knew O’Brien well enough to know how to resist him.

“But at some point, I realised these guys need a theorist. They need someone actually to work out the architecture. That’s going to take a big team, and they’re not going to be able to build that team, so I need to be part of this crazy idea.’”

Rudolph took leave from Imperial College, expecting he’d be back in two or three years. He knew building things always took longer than expected, but he was the theory guy. Surely, he could get that done in two years if he was any good. He looks back now, astonished at his naivety. “If you look at the history of classical computing, it’s never ended. You start with these massive machines, and then the very next thing you do is say, Well, I’ve got to make this thing smaller and faster and use less power. It’s exactly the same with quantum computing. There is no end.”

None of the founders wanted to live in the “infinite, never-ending suburbia” of Silicon Valley, recalls Shadbolt. “The compensation for that is that very, very strange and interesting things are going on. This guy is building a fusion company. This woman’s building rockets.”

Rudolph can’t watch Silicon Valley. It’s too close. “It’s hard to explain – the levels of hubris and enthusiasm and skillsets. Everywhere you go, there are scientists and engineers, whether at your local coffee shop or wherever. The incubator we were in had robots walking around.”

Playground’s incubator was PsiQuantum’s office, with old arcade games, a motorbike collection, amazing food and a fake tree. And it felt different in other ways. “In academia, you work with smart young people and they keep disappearing on you. Here, you work with smart people, and they’re there for years as you build a strong intellectual dynamic. You know who knows what.”

Shadbolt says their ability to disagree has been key to surviving. “I’ve seen these guys in deep, academic combat with each other. It’s healthy that a bunch of over-educated people can get into an intense fight over some technical decision and then walk away with A, a conclusion, and B, smiles, and go to the pub and play pool. That has turned out to be a very consistent pattern. They can be eye-wateringly forthright.”

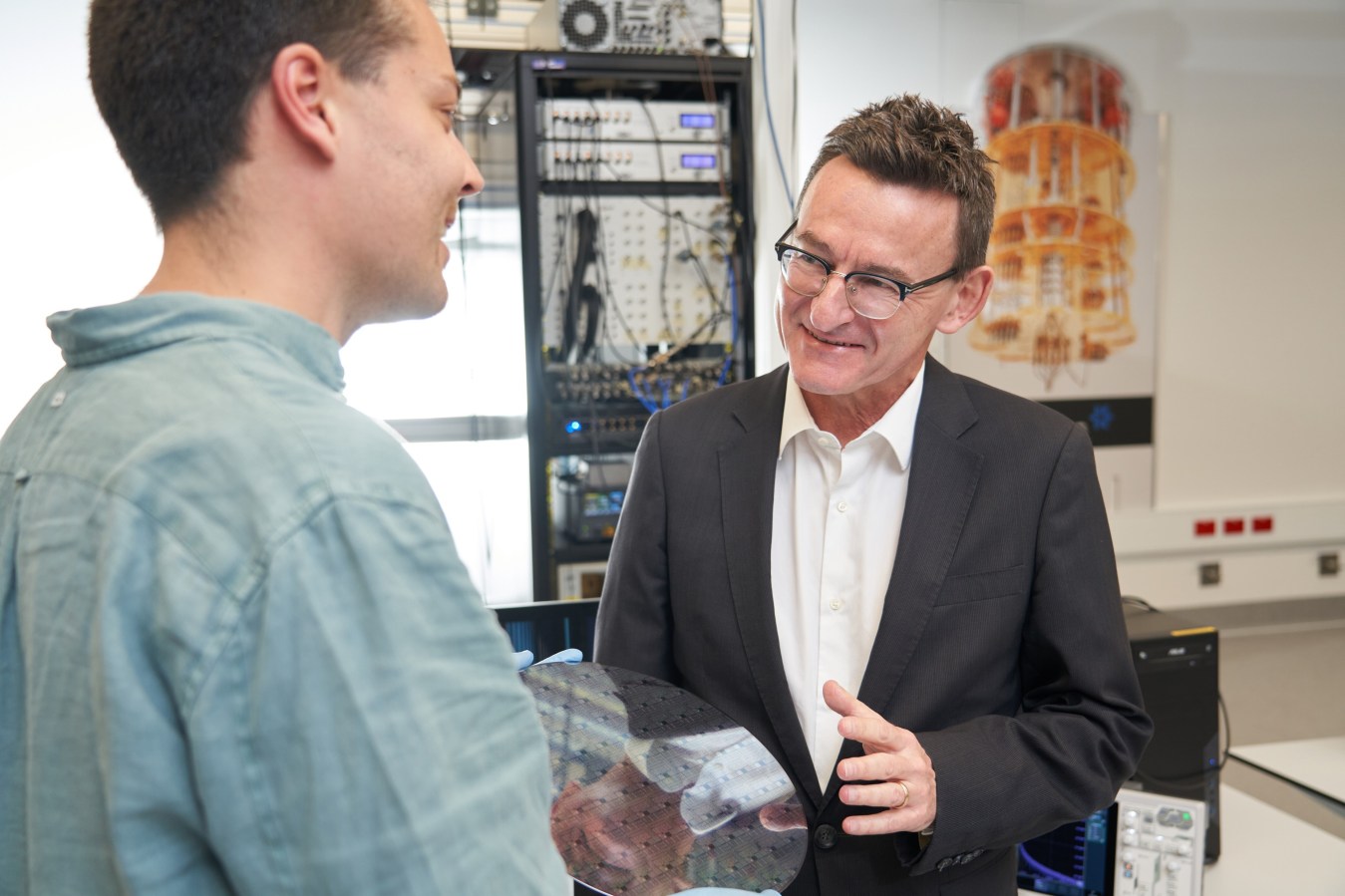

O’Brien says most of the money is now spent on engineering, not science. Eighty per cent of the staff had never previously worked in quantum anything. But they knew how to build stuff. An early highlight for O’Brien was when they got an ATE [automated test equipment] for testing silicon wafers. He didn’t know any university in the world that had one. At a university, a grad student would do such things.

“My back-of-the-envelope calculation was that this machine did the job of about 100,000 graduate students. Now we have six of them running around the clock.”

Building it

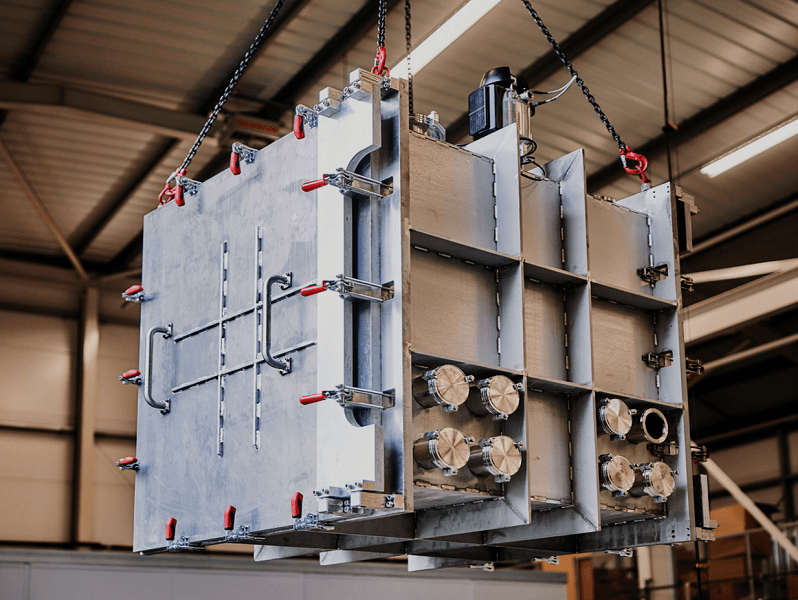

As PsiQuantum’s chief scientific officer, Pete Shadbolt had been nagging the rest of the team for years. “You picked your fab, [chip manufacturer]” he’d say. “You figured out some of your contract manufacturing. You figured out how you’re gonna build the cabinets, but if you’re serious about the timeline, where are we building the thing?”

Shadbolt has two galling habits, says O’Brien. “He always thinks he’s right. And he always is. That’s a really annoying combo.”

Around 2020, they started looking for a place to build the world’s first useful quantum computer.

Peter Verwer had the lofty title of Prime Minister’s Special Envoy for Global Business and Talent Attraction. The Morrison government, says Verwer, saw COVID-19 as an opportunity to reach out to the “most talented people and firms in the world” to bring them to Australia. The highfalutin title meant he could get straight to their CEOs to see what they wanted. In June 2021, he got to O’Brien, who, from the beginning, made it clear they wanted a lot.

“Our view was they’d need to make the case mainly to the states and territories,” says Verwer, “Because it’s the states and territories that offer the incentives in Australia, speed up planning approvals, give payroll-tax holidays and other incentives.”

O’Brien says that because PsiQuantum’s computer would be around for a long time, his priority was a long-term partnership, where he could be certain of stable government, a well-educated workforce and a thriving economy. He says that not everyone in the company was sold on the idea of building it in Australia. They were also looking at Europe, the UK and the US. “I said, ‘Trust me, you go speak to these people.’ It was like a breath of fresh air – people who want to get things done, who understand what it’s going to take.”

All the states wanted it. They’d heard the claims about how big quantum computing could be. “So job number one was to have a beauty parade,” says Verwer. “All states were given the opportunity to participate – Queensland got it in the end. It had the greatest appetite from the beginning.”

On the money side, Verwer says PsiQuantum’s ask from the beginning was not unlike the $940 million they eventually got. The intention under the Morrison government, though, was that they would need to tap into the pre-existing 1,700 different research incentive programs that “added up to a bucket of money worth, in those days, about $69 billion”.

After the Morrison government’s 2022 election loss, Verwer’s job ceased. The Albanese government continued the conversation under its Future Made In Australia banner. In August 2023, the federal government called for expressions of interest from 21 Australian quantum companies – after Canberra had already been talking to PsiQuantum for years.

Australia’s Chief Scientist, Cathy Foley, advised the government on the investment. She told the media that the EOI process was to see if any other candidates could build such a computer, but that her assessment showed PsiQuantum was “a country mile” ahead.

It culminated in the deal announced in April whereby the federal and Queensland governments each took US$125 million in PsiQuantum equity and agreed to each loan AUD$280.5 million to the company for a total deal worth AUD$940 million.

Even though it was a deal started by their own side of the parliament, the Opposition was furious. The companies who’d taken part in the EOI were sworn to secrecy, so they could not comment on the deal. But Opposition industry spokesman Paul Fletcher said he had talked to some of those companies who privately expressed disquiet. “They’re now in a position where they go to global investors, and those investors know the Australian government has conducted what it says is a comprehensive search to find the best quantum technology, and it’s specifically not chosen any of the Australian-based companies. This is quite unhelpful for other participants in the sector.”

Fletcher met O’Brien in a video call soon after the deal was announced. Fletcher wanted to know if there were performance milestones in the contract and if any security was taken over assets for the loan. “It was an amicable conversation,” says Fletcher, “but he [O’Brien] was unable to give us the details that we were interested in.”

The policy of picking winners is a bad strategy, says Fletcher. “It’s not an Australian company. It’s an American company. It has four founders. Two of them did degrees in Australia, but neither has lived and worked in Australia for 20 years. How it’s been presented as bringing Australian technologies back home is rather curious. It’s understandable that many of the participants in Australia’s vibrant quantum computing sector are troubled by what has happened.”

Professor White says the PsiQuantum deal was not picking winners. He points out that the Queensland Government announced $89.7 million in grants to quantum companies in its last budget. “It’s like building a shopping centre. You want an anchor tenant, but you want all the others as well.”

White cites the vast amounts that Australian governments have pumped into quantum over two decades. “It’s grabbing attention now because it’s the biggest single investment, but it’s not like it’s the only one. There’s a long tail.”

On that note, another of O’Brien’s collaborators on that seminal 2003 Nature article, Geoff Pryde, recently rang White. “You know how we used to joke that everyone would end up working for Jeremy? Well, guess what?”

Professor Pryde had taken leave from Griffith University to work for PsiQuantum.

Schrodinger’s Cat

Terry Rudolph’s grandfather, Nobel Prize-winning physicist Erwin Schrodinger, devised a famous thought experiment known as Schrodinger’s Cat. Quantum mechanics dictates that the properties of particles assume fixed values only when measured. Before that, a particle exists in a “superposition” of many states at once. To make it easily understood, Schrodinger used the example of a cat locked in a box with a vial of poison. The cat “super positioned” in a state between life and death until someone opened the box and confirmed if it was alive or dead.

Rudolph is one of the authors of the PBR Theorem, which similarly seeks to explain the quantum world. “Our classical thinking about the world is very ingrained into us as humans,” says Rudolph. “Science is premised on assumptions; for example, I can isolate myself in this room and do an experiment, and I don’t have to worry about what’s going on at Alpha Centauri. We have a lot of ingrained biases towards things like locality and things we can measure. We think we’re special, but really, in a physics sense, we’re just an intermediate-sized monkey. We’re not small like an atom or big like a galaxy. We also have a bias towards narratives that are on a scale similar to ours.

“So we have this challenge of working out how much of our science is contingent on the way that we’ve experienced the world. Because we evolved to chase bananas and mate, we have a particular set of things that we need in terms of the narratives of the world around us It might be fundamental, but it might also just be because of the types of creatures that we are.

“So you have these theorems, and PBR is one. Schrodinger’s Cat is another, which are really about trying to tell us where those stories can or cannot be used. It’s fun stuff.”

Normal computers use the same narrative as us mid-sized monkeys: true, false, yes, no. “The difference with the quantum computer is you have that same logic plus one more logical principle. And it’s that extra kind of logical gate that gives the quantum computer its power Ð it can use many fewer steps than a classical computer to solve a problem .”

Firing it up

The site at Brisbane Airport will break ground at the end of 2024 or early 2025.

There will be two buildings. One is a major “cryo plant” that cools helium to a liquid and pumps it into the building next door, which will look like a data centre full of cabinets and racks. Co-founder Terry Rudolph, ever the theorist, can’t wait to get onto the machine and start using it. “The nice thing about this technology is that everyone wants it for its different applications.

But one of the things quantum computing will be good for, is solving problems of quantum mechanics.”

It’s been said that quantum computing might win the Nobel Prize for physics, but chemistry will write the cheques as its quantum’s power gets turned to creating hitherto unknown products.

If they get this working, there will be vast demand for limited time on the machine. Rudolph finds himself in a position to, maybe, jump the queue. “But whenever I tell people on the business side of the company this, they’say, ‘I hope you’re feeling rich because you’re going to need it to run stuff on this machine.’”

That problem, however, isn’t coming soon. Even if they make their 2027 deadline for finishing the world’s first error-corrected, functional quantum computer, Rudolph says it probably won’t meet his needs. “The things I’m interested in will require huge quantum computers – 10-times more than the one we’re building. How long it takes to make that jump? I don’t know.”

Quantum entanglement: Aussies leading the global private-sector quantum race

Name | Position | Company/Institution | Location | Educational Background |

|---|---|---|---|---|

Jay Gambetta | Vice President | IBM Quantum | New York, USA | Griffith University (Undergraduate), ANU (Undergraduate), Griffith University (PhD under Prof. Howard Wiseman) |

Christian Weedbrook | CEO & Founder | Xanadu | Toronto, Canada | ANU (Undergraduate), University of Queensland (PhD under Prof. Timothy Ralph) |

Devin Smith | CTO | QuiX Quantum | Netherlands | University of Queensland (PhD under Prof. Andrew White in Prof. Gerard Milburn’s group) |

CEO & Founder | Silicon Quantum Computing | Sydney, Australia | Recruited from the UK by Prof. Bob Clark at UNSW | |

CEO & Founder | Diraq | Sydney, Australia | Cambridge University (PhD), UNSW (Joined Bob Clark’s team) | |

David Reilly | Former Head of Quantum Team | Microsoft (now about to form a start-up) | Sydney, Australia | UNSW (PhD under Bob Clark and Prof. Bruce Kane) |

Jeremy O’Brien | Co-founder & CEO | PsiQuantum | USA | UWA (Undergraduate), UNSW (PhD under Bob Clark), University of Queensland (Post-doctoral work under Prof. Andrew White) |

Terry Rudolph | Co-founder | PsiQuantum | USA | University of Queensland (Undergraduate under Prof. Gerard Milburn), Toronto (PhD) |

Winfried Hensinger | CEO & Founder | Universal Quantum | UK | University of Queensland (PhD under Prof. Halina Rubinsztein-Dunlop and Gerard Milburn) |