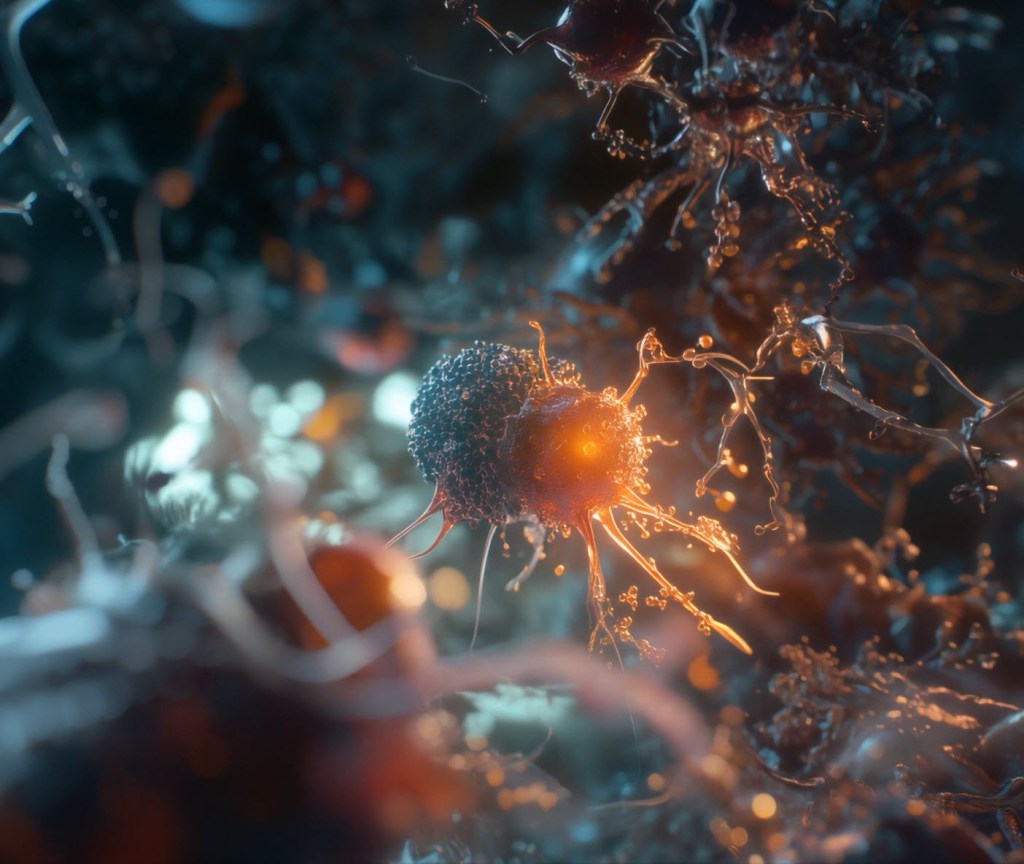

There’s a revolution going on in cancer treatment with more than 1,000 clinical trials underway into CAR-T therapies promising an immune response up to 1,000 times stronger than ordinary immune cells. Chasing a market worth billions, we take a look at three Australian biotechs with their elbows out.

“We take your immune cells, we engineer them in the lab, we teach them how to fight cancer very well, and then we give them back to you,” explains Dr Rebecca McQualter, CEO of Chimeric Therapeutics, explaining the guts of what CAR-T therapies do.

Why is Chimeric going to succeed amid more than 200 companies and 1,000 ongoing studies all working to crack the CAR-T therapies market?

“We’ve got a good one. We’ve got a Ferrari,” McQualter tells Forbes Australia.

The company is trialling three drugs. Its lead candidate is a CAR-T targeting gastric and neuroendocrine solid tumours.

McQualter joined the ASX-listed company in 2024, becoming its only employee in Australia. She’s an Australian scientist who was “aggressively headhunted” back to Australia by founder Paul Hopper in 2024 after 13 years in the US with big pharma.

Chimeric had enjoyed an early stock market glow after listing on the ASX in January 2020 but has since settled into the money-draining slog of drug development, with its shares [ASX: CHM] bumping along the bottom around $0.003, with a market cap around $11 million.

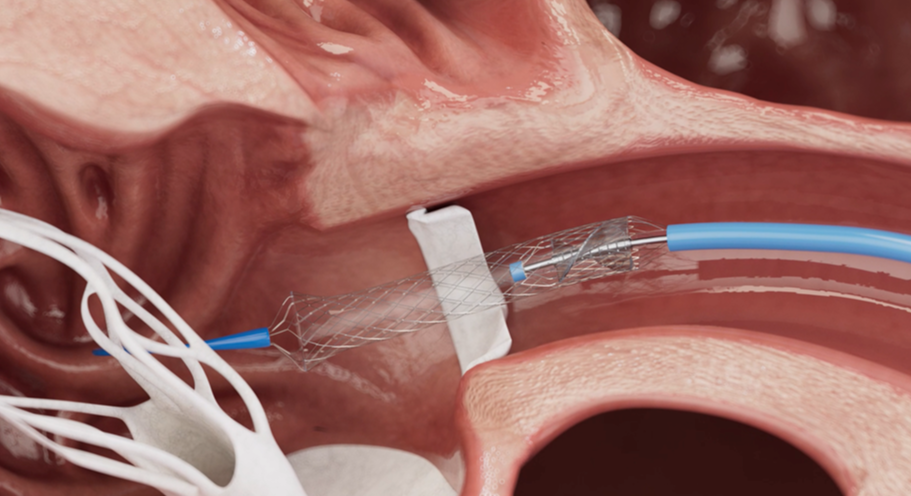

CAR-T stands for Chimeric Antigen Receptor T-cells therapy. There are currently seven CAR-T therapies on the market in the US and four in Australia. All of them target blood cancers like lymphoma and leukemia.

Solid tumours, however, are a tougher nut to crack.

That’s where Chimeric’s CAR-T comes in. “How I explain it to my retail investors,” says McQualter, “is that with blood cancer it’s a one-on-one fight. It’s kind of equal. But when you go up against solid tumours, it’s like climbing Mount Everest. It’s a big rock.”

“Just these four drugs alone have been doing more than US$3 billion annually. And that will keep growing.”

Leslie Chong, Imugene CEO

Chimeric’s IP was bought out of the University of Pennsylvania. “It’s got two V-12 engines on the back. So it can really push into the cancer and start killing it quickly,” McQualter says.

Chimeric has been tested in 10 patients in the US since late 2024, all with late-stage cancers. “We really like what we’re seeing,” she says.

McQualter cites one female patient with stage-4 bowel cancer who received the single dose last December. “She’s got no new tumours, her tumours stopped growing … and she hasn’t had any other treatment … We get end-of-the-line kind of patients who typically live between three and six months, but we’re out at nine months now with one dose. It was, like, not even half a tequila shot worth of cells.”

All existing CAR-T therapies involve patients having their blood taken, their T-cells isolated and genetically engineered to soup-up their cancer fighting propensity. That takes about nine days, says McQualter. But it then takes another 20 days for the dose to pass through various regulatory hoops so the patient receives their therapy dose about a month after the blood is taken.

If it gets approved, a dose of Chimeric’s CHM CDH17 will cost about US$500,000 in the US. It likely won’t need to do a Phase-3 trial.

“We’ve got a couple of potential partners looking at us right now because it’s a really hot target,” says McQualter. “The bowel cancer space is growing rapidly and evolving. To execute a decent Phase-2 trial is about US$50 million. So I hope one of the big boys that I used to work for will come to our rescue and chip in.”

“I invest in stuff where I think there’s a really good risk-reward.”

Charlie Williams, managing director of HB Biotechnology

The treatment has been granted a fast-track approval process by the US Food and Drug Administration [FDA]. “That means they’re gonna do everything in their power to make sure we tick all of our boxes and get on the market quickly. It’s really only money standing in our way … We can finish phase two in about eight months … if I get the money I need.” She laughs.

One of the great drawbacks of all existing CAR-T therapies has been the cost and time it takes to individually engineer each patient’s own T cells. They’re called autologous, or auto CAR-Ts. Not to mention that only about half of all patients get a significant benefit. But there is, perhaps, a solution at hand.

Imugene: Off the shelf

“81% overall response rate,” Leslie Chong opens the conversation with Forbes Australia. “Can you imagine going to a doctor after you’ve failed off other auto CAR-Ts and chemo, and you’re on your way to a hospice … And the doctor says, ‘you’ve got 81% chance of this drug giving you a response, abating your cancer or lowering your tumours, or what have you?’ It’s phenomenal!”

Leslie Chong also owes her presence at the top of an Australian cancer-fighting start-up to Paul Hopper. The American-born now-Australian citizen came in 2015 to head up Imugene, which had been set up by Hopper in 2012.

The company enjoyed a crazy stock market ride up to $20 a share in the COVID-19 bio-med frenzy, but is now worth one sixtieth of its peak valuation, with a market cap currently at about $100 million.

“When I came in 2015 we were developing cancer vaccines,” Chong says. “Then in 2019 we started developing oncolytic viruses – viruses that attack cancer.”

In 2023, the company bought some IP from Nasdaq-listed Precision BioSciences which had used Duke University gene editing tools to create a CAR-T that didn’t need to be developed out of the patient’s own T cells.

“So we are off the shelf,” says Chong in explaining why Imugene is a good bet to get to market, even though it targets blood tumours like the existing CAR-T therapies. “We take healthy donor T cells. We engineer those outside of patients. So one batch of drug can dose multiple patients and there is no rejection.”

“We’ve been scouring the world, creating relationships with outstanding professors and licensing different technologies.”

Michael Baker, Arovella CEO

Patients can therefore receive Imugene’s “Azer-cel” on day one of their treatment – as opposed to waiting a month for existing CAR-Ts – and they will pay about one-tenth the price, says Chong.

Imugene has five sites in Australia and ten sites in the US where Azer-cel is being trialled in patients in a Phase 1B trial. “We’re in cancer patients who have failed off [other CAR-T therapies].” These are the ones who are getting the 81% response rate to Azer-cel, all of whom have failed multiple other treatments.

“Yescarta, Kymriah, and Breyanzi are all approved auto CAR-T therapies, and they got approval in the same indication with a 54% response rate,” says Chong.

No off-the-shelf CAR-Ts have been approved for market by the FDA. “We think we could be the first,” says Chong. Imugene is still working on its other drugs but is focussing its efforts now on Azer-cel.

The company recently raised AUD$46 million and so has the money to get into Phase-2 trials.

Its potential market is large. “There’s been a 50% compound annual growth and I think it will keep on growing,” says Chong. “Just these four drugs [attacking the same receptor as Imugene] alone have been doing more than US$3 billion annually. And that will keep growing.”

Risk and reward

While enthusiasm for CAR-T therapies is high, Charlie Williams, managing director of HB Biotechnology, takes a more measured view.

Williams, who advises high-net-worth and wholesale investors on biotech, has not directed his clients toward CAR-T programs.

“And I want to be very clear. It’s not because I don’t think they have chances at showing a difference. I invest in stuff where I think there’s a really good risk-reward,” he says.

“There’s a big financial element to it. The whole ecosystem of CAR-T is high-cost and high-risk in a crowded market. It just makes me think there are other better risk-reward opportunities for my clients elsewhere.”

Instead, Williams has steered clients toward bispecific antibodies — a related but distinct approach that links a cancer cell to an immune cell to trigger an immune attack. “Wherever CAR-T goes, the bispecifics can go too,” he notes. “The upside is huge — but the balance between science, safety and commercial reality still matters.”

Arovella: Natural-born killer

Another Australian biotech, Arovella, is also taking a different route. Dr Michael Baker, CEO of Arovella, was recruited in 2019 by Paul Hopper to help build yet another company focused on next-generation cell therapies.

“We set about bringing in really novel, cutting-edge intellectual property from the world’s best research institutes and universities worldwide,” Baker says on a video call. He was surprised how long it took. But after 18 months looking at more than 100 potential technologies, he found what he was looking for at Imperial College London, where Professor Tasos Karadimitri was working with natural killer cells.

Unlike the more established CAR-T or CAR-NK approaches, Arovella’s lead program leverages invariant natural killer T-cells, or INKT cells — a cousin of the standard T-cell.

Baker believes the invariant natural killer T-cells offer advantages in both scalability and potency. “These little INKT cells, they’re just less well-studied, but they can be freely given from one human to another,” he explains. That means, unlike traditional CAR-Ts, doses don’t need to be custom-made from each patient’s own blood, opening the door to off-the-shelf treatments that can be scaled efficiently.

Early preclinical results have impressed Baker. Head-to-head tests in mouse models showed CAR-INKT cells outperforming traditional CAR-T therapies, prompting the company to rapidly translate the technology from research scale to commercial-grade manufacturing.

“What happens in the lab is very different from what happens when you try to make a reproducible, scalable product,” he notes. The team has spent the last several months fine-tuning manufacturing protocols to meet the standards required for clinical trials.

Arovella is poised to enter Phase-1 trials in early 2026, targeting blood cancers with its lead INKT therapy. But that’s where the elegance of the business plan kicks in.

Baker and his team are preparing investigational new drug applications with the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to create a blueprint for multiple future programs. “Once we get the okay from that, we can apply the same INKT model to other cancers,” he says.

“We’ve already been scouring the world, creating relationships with really outstanding professors and licensing different technologies that will then enable us to use the same INKT cells to target things like gastric cancer, pancreatic cancer, we’re looking at nasty central nervous system cancers in young children, hepatocellular carcinoma, which is a form of liver cancer.”

He says that in the time since they bought the tech, a number of articles have been published in the literature showing INKT cells could target solid tumours. “We didn’t fully appreciate that when we licensed the technology. We couldn’t. Some of this work didn’t exist.”

For Baker, the strategy is clear. “It’s now get it, prove it, and then use it to build out,” he says.

The company has raised about $50 million since 2020. “We’ve reported $21 million cash in the bank at the end of June 30.” Enough to take them through to patient recruitment.

He doesn’t see Arovella as competing with other cell therapy start-ups.

“The notion that at some point we’ll have a silver bullet that cuts through every type of cancer, that’s long gone. What we need is clever people figuring out what we need to do, probably on a patient-by-patient basis, what combinations of products we need to put together … so that’s a matter of how do we work together, rather than how do we compete against one another.”