Australia’s well-educated population, stable political system and relatively benign regulatory environment should make it a world leader when it comes to innovation. But we consistently rank below our peers on innovation indexes. Forbes Australia looks at some of the companies bucking the trend.

Why does Australia consistently rank lower than its western peers for innovation in global indexes? The 2021 Global Innovation Index by the World Intellectual Property Organisation, which analyses things such as human capital, technology and creative output, ranks Australia 25th for overall innovation, far below the US (3rd) and UK (4th).

Other indexes also mark Australia poorly. The Australian Productivity Commission’s 5 Year Productivity Inquiry into innovation found that only 1-2% of Australian businesses are producing ‘new to the world’ innovation. One of the reasons, says Commissioner Dr Alex Robson, is that the minimum rate of return required on a project or investment is too high. “Whether that’s because of uncertainty that’s specific to their industry or uncertainty overall, the data suggests that it’s remained pretty high in Australia,” he says.

Deloitte managing partner, consulting, Ellen Derrick says the great thing about Australia is the opportunity. “It’s phenomenal,” she says. But she notes that the national economy has historically relied on natural resources, with mining being the primary contributor to the economy, especially iron ore. Australia’s iron ore export earnings reached $133 billion for the 2021-22 financial year, with iron ore in the Pilbara alone worth 5% of the nation’s GDP.

Derrick says Australia shines when it comes to research, but development or commercialisation of that research doesn’t always follow. But she thinks mindsets are changing, and says Australia is well-placed to move to the forefront of emerging technologies in space, health, climate technology and decarbonisation, as well as in technology that can help feed the world.

Forbes Australia has identified four companies at the forefront of change who are disrupting their industries and commanding investor attention.

Fleet Space

Rocket scientist Flavia Tata Nardini is at the helm of one of Australia’s largest space companies, Fleet Space, which she founded in 2015 with Alauda Aeronautics founder Matt Pearson. With much of the world unable to access 4G and 5G, Fleet’s mission is connectivity.

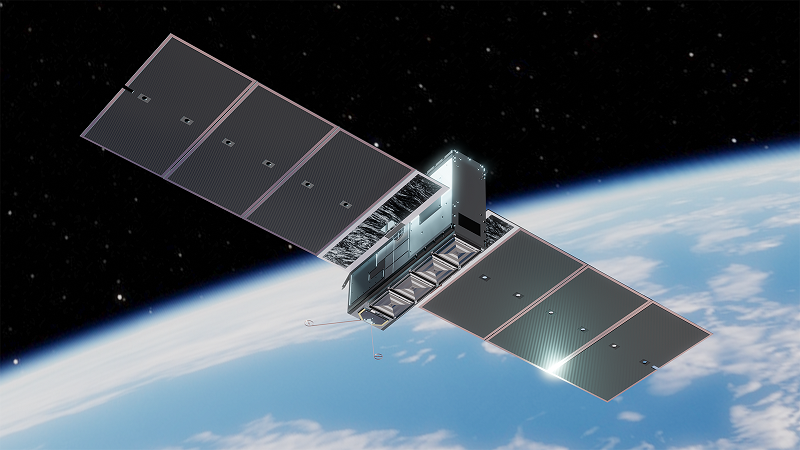

Its ExoSphere technology scans the ground listening for quakes and waves using real-time ambient noise tomography (ANT) to determine what kind of minerals are buried there. 3D-printed nanosatellites the size of a shoebox and flanked with antennas and solar panels, orbit the earth receiving data from the ground in real-time. “It’s cool, right?” Nardini says.

Fleet’s machines are looking for critical minerals such as lithium, nickel and copper. They’re in high demand, and often miners spend months drilling holes into the Earth to find them. Fleet Space can do it all in days – without a single drill. “It felt counterintuitive – that we need to drill the Earth to find the critical minerals we need to save it,” Nardini says.

Fleet Space is now valued at US$126 million after a US$26 million capital raise in November last year led by Grok and Blackbird Ventures. It’s impressive considering Fleet Space operates out of a few warehouses in Adelaide, a city that reminds Nardini of Mars. “It’s far away, it’s red… it’s perfect for space companies.”

But how did a rocket scientist from Rome go from working at the European Space Agency in the Netherlands to the other side of the world? For family, the mother of two says. Adelaide is her husband’s hometown. And while she found the adjustment tricky, Nardini eventually found her feet – and her calling – with nanosatellites. A self-described “nerd”, Nardini first learnt about nanosatellites at university, where they were used mostly for earth observation.

Then she saw Silicon Valley companies commercialise them. Elon Musk was already talking about launching Starlink satellites to provide broadband to remote areas, so Nardini decided to focus on connecting machines rather than connecting people. “I didn’t want to fight with Elon and his infinite bucket of money,” she says. But she and Musk would prove to be a good team.

Fleet now ships its nanosatellites to Musk’s spaceship company, SpaceX. Fleet also finds lithium for ASX-listed Core Lithium, which supplies the metal for Musk’s Tesla and its car batteries. Musk is just one of Fleet’s 23 clients across Australia, the US, Canada, Chile, and Greenland. When its new operating site is up and running near Adelaide’s airport, Fleet – which also has Australia’s largest 3D printer – plans to launch 50 to 100 nanosatellites a year.

Nardini’s longer term plan is to apply to NASA to take its satellites and ANT technology to the moon and Mars. “Imagine if we found water out there, without damaging the planets,” she says, explaining how she doesn’t want corporations digging up other planets.

iiShield

Organ transplant surgery is a complex and invasive procedure. The more time a surgeon has to complete the transplant the better off the patient will be. When it comes to kidneys, one in four transplants fail within five years. That’s where iiShield steps in.

The startup was created to find a way to increase that time. The solution? An innovative ischemic injury protective jacket, affectionately known as the kidney pyjamas. Kidney transplants take an average of 41 minutes to perform. Not long after a kidney is taken off ice to be transplanted, it starts to warm up and for every 10 minutes it is above 15°C, there is a 10% increased risk of kidney failure and a 63% increased risk of delayed function. It’s a high stakes situation, says pancreatic surgeon Tony Pang.

“There’s this huge pressure… especially when you know the kidney is being damaged, and so you get all this shaking and tremor because you want to do it quicker,” says Pang. “But the paradox is that because you want to do it quicker, you’re doing it slower because of all the stress.” Pang was an innovative surgeon at Sydney’s Westmead Hospital when he was introduced to biomedical engineer Jeremy Kwarcinski by professor of surgery at Westmead Henry Pleass.

The three men, and another biomedical engineer, Turaab Khan, co-founded iiShield a couple of years ago. At the time, Kwarcinski had just finished his engineering PhD and was working with a few startups, toying with the concept of protecting organs during transplants. “We threw together a few quick prototypes and the results were really promising,” he recalls.

The first prototype was made of a few pieces of medical-grade silicone sticky-taped around a pig kidney and thrown in a water bath. The team stuck some temperature probes into their creation and found they had helped protect the kidney.

Eventually, they validated their theory with some discarded human kidneys that weren’t good enough for transplantation. The latest iteration looks like a silicone pocket the size of a mousepad, with one open side. The kidney is slotted into the pocket, the pocket is placed inside the patient and the surgeon attaches the organ to the arteries and veins from the open side. Finally, the pocket is removed.

The benefits are two-fold. “There is this incredible time-pressure on surgeons to do operations – not only perfectly, but as fast as possible,” Kwarcinski says. “So, what we’re finding is that we are not only protecting the kidney from the heat of the body, but we’re also allowing surgeons to be more relaxed knowing they have the time to do it and do it right.”

In 2021 iiShield received a $2 million grant from the Medical Devices Fund (MDF) allowing its founders to move to the next stage. “We didn’t believe it,” Kwarcinski says. “We got an email from [the MDF] team asking to meet us in two weeks, and I remember thinking, ‘Is that a good thing?’ “It was a pretty nerve-racking two weeks, but when we got there and found out, it was life changing.”

The team have since received ethics approval for a clinical trial. They’ve also submitted to the FDA for regulatory approvals to begin collecting clinical evidence. They will perform the clinical trials in Australia but receive regulatory approval from the US. “It’s a numbers game,” Kwarcinski says. “There are about 100,000 kidneys transplanted globally each year. Only around 1,000 are done in Australia, where almost 30,000 are done in the US.”

The team also hopes that by gaining FDA approval first, the TGA will follow. If all goes to plan, the kidney pyjamas will be available to surgeons in the next 18 months, without another capital raise in between. “We’re hoping the MDF can take us all the way to commercialisation,” Kwarcinski says.

Plotlogic

Andrew Job has been in the mining industry longer than he cares to mention but he’s spent almost as long reckoning with the notion that while the world wants to move away from fossil fuels, we shouldn’t dig up more earth and further damage the environment in the process. So, he quit his job as general manager of Anglo American’s CapFox operation in Mackenzie River, Queensland, to found and run Plotlogic, a mining tech company that aims to increase the uplift of mines, reduce waste, and help the environment.

So far, the company has raised $25 million from BHP and former Google CEO Eric Schmidt’s Innovation Endeavours. The startup is dealing with four of the world’s top five mining companies and, on some estimates, could exceed $100 million in revenue in just over 12 months. The concept is simple, Job tells Forbes Australia. A superhuman brain – about the size of a microwave oven – equipped with four “eyes”, scans rocks at different points in the mining operation, and uses artificial intelligence to understand what the rocks are made of.

There could be one used at the beginning of the process when mines are being drilled and rocks are being blasted. There could be one used to scan the debris and exposed rocks, another mounted to shovels and excavators, and another attached to stockpiles and conveyor belts. “We basically look at the entire mining system, end-to-end,” he says.

“We use our technology to really go in at the nano scale and identify, rock-by-rock, what’s happening, and use that to lift the yield of the mine and reduce the amount of waste.” This AI scanning technology has two benefits: it unlocks value in existing operations and makes new operations more efficient and less wasteful than they otherwise would be.

The technology can also identify other issues that could cause operational problems or even shut down mining. Job’s industry experience meant he understood the problem; he had to undertake a four-year PhD to find a solution.

“When I worked out that I wanted to use this particular type of sensor, there were really only three of four manufacturers in the whole world that produced it, and it was mostly used in lab settings.” He flew to Finland, Norway, and North America to meet with the manufacturers: “No one was more surprised than them when I said, ‘I’m actually going to buy a couple of these things’.”

Job re-mortgaged his house to buy the $250,000-sensors. Thanks to deals with Glencore, Anglo American, Vale and BHP, he has been able to pay off his house once again, he says. “We’ve had massively strong support from the VC community out of Silicon Valley.”

Magic Valley

The plant-based meat industry has been gaining significant traction over the past few years, with estimates valuing the market at US$8 billion this year, with a CAGR of 14.7% between now and 2027. Australia has some major skin in the game (for example, V2 Foods, Fable Food Co), but there is a new player entering a parallel industry: cultivated, or cell-based, meat products.

Magic Valley is a Melbourne-based cellular agriculture company founded by entrepreneur Paul Bevan in 2020. It recently closed a $5 million seed capital raise that valued the company at $20 million. Bevan tells Forbes Australia he has always been interested in ethical products that remove animals from the supply chain.

His background, however, has been in business, finance, and investment: he founded Capital V, a venture capital firm that specialises in early-stage investments in companies that want to build a better world for animals. “I have invested in a number of plant-based and cultivated meat companies that are overseas, and I’m very aware of the technology of cultivated meats,” he says. “To me, that’s really the answer, because there are so many benefits to cultivated meats.”

Magic Valley recently created its first prototype, lamb mince in the form of burgers and tacos. Mince requires less structure and it easier to develop than meat on the bone, such as chops. To create the product, the company took a small skin biopsy from a lamb named Lucy (still happily living in a field in NSW). The cells were turned into induced pluripotent stem (iPS) cells, which can enable the development of an unlimited source of any type of human cell, and can be made into muscle and fat.

“The structure of the product, molecularly, is identical to traditional lamb products, because that’s exactly what it is,” Bevan explains. It’s the first time this technology has been used to create a cultivated lamb product. Magic Valley’s major competitor is Australian alternative protein company Vow, which is back by Blackbird and Square Peg.

However, Magic Valley claims that, unlike its competitors, it does not use fetal bovine serum – a by-product of a pregnant cow being slaughtered – to create its products. “The $5 million that we are raising is going to help us with the development of our products and for further development of our lamb prototypes,” Bevan says. “We’re also looking at other species, and meat products, like pork and beef, and the capital will help us scale.”

Bevan estimates the company will have its range of products on dinner tables by 2024, with no animal involvement outside of Lucy’s skin scraping. By 2040, it’s forecast that cultivated meat will contribute to more than a third of the $1.8 trillion global meat market. It could also reduce global greenhouse gas emissions by 92%, Bevan says.

There could also be health benefits from this sci-fi like food source. “Because we’re in a lab setting, we’re able to add additional nutrients. For example, it might be vitamins, or it might be Omega-3. Anything that people see is beneficial to a nutritional profile,” he says. “We have control over the components that go in from the muscle cells, the fat cells, so we can remove saturated fats, or add in additional protein content – or whatever people might desire.”