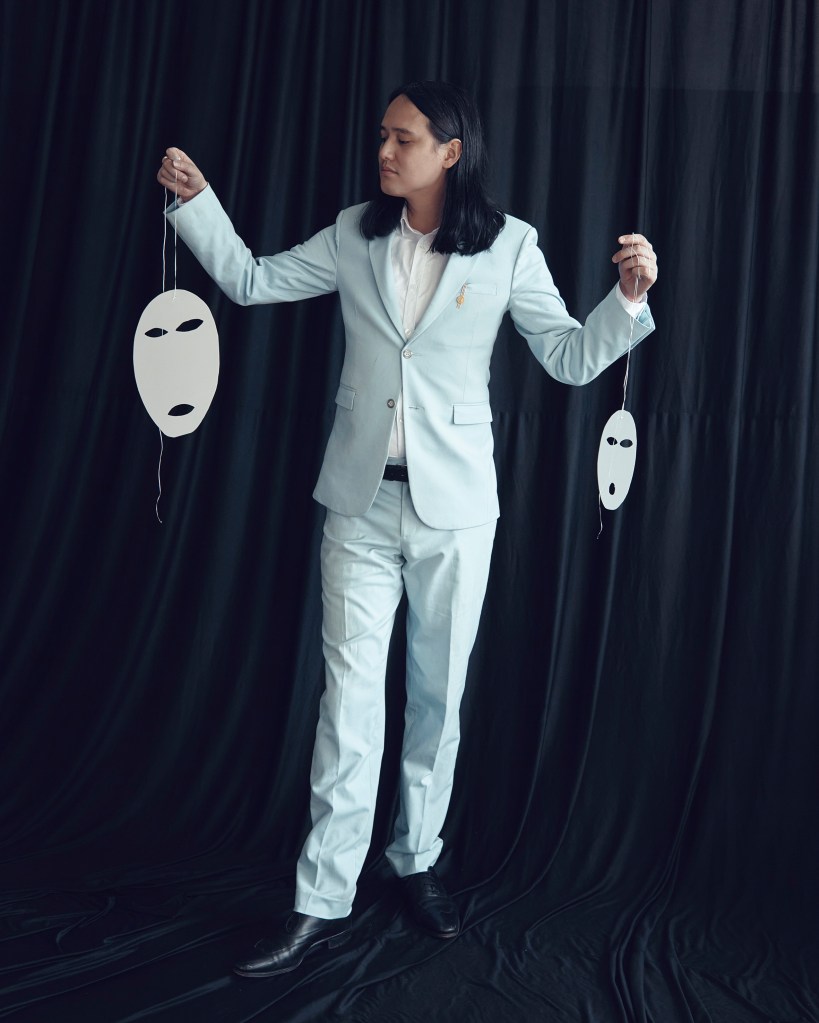

Australian technology entrepreneur Hoan Ton-That is the CEO of one of the world’s most controversial facial recognition companies. His database of 20 billion photos is being used to crack crimes around the world but human rights groups and some regulators – including in Australia – have concerns.

Hoan Ton-That has been accused of many things, not least of which is single-handedly destroying privacy by bringing Big Brother tech to life. His facial recognition company, Clearview AI, has been described as secretive and unethical.

The 34-year-old shot to prominence in early 2020 when Clearview AI’s practice of sourcing billions of ‘face prints’ from the web was revealed by The New York Times. Since then, his New York-based AI company has been hit with hefty fines by some regulators and has received cease-and-desist letters from the likes of Google, YouTube and LinkedIn. Its software has been banned in Australia, the European Union and Canada.

Despite this, Clearview AI presses on. Its database now contains a staggering 20 billion images and based on its capital raising, the company is valued at about US$130 million ($207 million). In 2021, Time magazine named the company one of the world’s most influential, while acknowledging that its innovative technology was causing grave concerns among some civil rights groups.

Ton-That’s demeanor throughout the interview is friendly and relaxed. He sheepishly admits that his Aussie accent has worn off. He offers to give me a demonstration of Clearview AI’s software. Ton-That’s sangfroid is rare in the tech world, where entrepreneurs who have generated negative headlines retreat under a cone of silence or issue hot-headed rebuttals that do their company no favours.

“Early on, a lot of people advised me not to speak to the media,” says Ton-That.

“‘It’s not worth it,’ they said. But working through the negativity around the technology has been rewarding. Not everyone’s going to agree with it and there’s always different perspectives. That’s just the way life is,” he says.

The first media interview Ton-That agreed to was with The New York Times in 2020, which headlined the subsequent story: ‘The Secretive Company That Might End Privacy as We Know It.’ The young CEO was soon inundated with requests to appear on prime-time American television. He agreed because he believes television is a useful medium for dispelling misperceptions about his software.

“When people see it for the first time, the ‘wow factor’ takes over. They can also see that we have only public photos [in the database],” he says.

Like Google, but for photos

Ton-That’s technology is so powerful it’s easy to understand why some people are worried about it. During the demo, he tells me to cover my mouth with my hand. He takes a screenshot, and within seconds I am looking at 48 photographs of myself returned by the Clearview AI search – including one where I am wearing sunglasses.

Facial recognition technology raises alarm bells for some very good reasons, says Mark Andrejevic, a professor of media studies at Monash University in Melbourne and the co-author of the book Facial Recognition.

“One reason is that it enables passive identification at a distance,” he says. “Another is the mode of data collection: people whose images are online for a range of reasons, such as for their jobs, did not expect that these images would be used to create a commercial app that could identify them without their knowledge or consent.”

Ton-That emphasises that Clearview is not stockpiling photos marked by users as private on social media networks. The database works like Google: it searches for what is publicly available on the internet.

He says the software is used by law enforcement agencies in the US and other nations, and only after a crime has been committed. It is not identifying people in real-time as they go about their daily lives. That kind of application occurs in China, where the government’s ‘social credit’ system tracks individuals and organisations to monitor their ‘trustworthiness’. Ton-That says he would never sell his technology to authoritarian states like China, Russia or Myanmar.

“It’s a cloud-based technology, which means that if a country [that was using it] was overtaken by an enemy, we could turn it off,” he says. “We can do the same if we find an egregious abuse of it.”

However, as Andrejevic notes, strict oversight is need-ed to ensure the technology is not abused by those given the power to use it.

“We know there have been examples in Australia and elsewhere of police abusing their access to personal information, so there needs to be strict controls to ensure there are records of how the technology is used, and [to ensure] that these are subject to supervision – ideally by independent entities that are not connected to the police.”

Clearview AI’s software was being used by law enforcement agencies in Australia until an investigation by the Australian Privacy Commissioner in 2021 found the use of the technology had breached the Australian Privacy Act. Clearview AI was ordered to destroy its database in Australia. It is seeking an administrative review of the decision.

“The decision in Australia [to ban the technology] has been especially heartbreaking because I’m from Australia,” says Ton-That. “I think it is a misunderstanding of intentions. The software is meant to be responsibly used by law enforcement. Australian police were using it and it was super effective, especially for crimes against children.”

Bias is not an issue

One of the biggest criticisms directed at facial recognition technology from groups such as Amnesty International is that it can lead to discrimination because people of colour, women and those with disabilities have been found to be at a higher risk of misidentification.

“Facial recognition technology raises alarm for some very good reasons.”

says Mark Andrejevic

However, Ton-That says that bias is not a risk in a top performing algorithm such as his. He claims the strength of his software lies in the fact that it has vastly more training data than any other.

According to the Washington Post, Clearview AI wants to have 100 billion images in its database by the end of this year, which works out at an average of about 12 photos for every person on the planet, assuming there are publicly available photos for everyone in the world.

“More training data means less bias because the algorithm has more examples to learn from,” he explains. “Many algorithms relied on a training set of celebrities, which didn’t have many South or East Asian faces, or people of mixed race like myself,” he adds. “The concerns about bias in facial recognition come from tests on algorithms that were done quite a long time ago in tech years – back in 2018.”

Clearview AI boasts the highest accuracy rates of any facial recognition algorithm used in the US and it was ranked in the top five of every category out of 650 algorithms globally, according to independent tests by the National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST).

Across every demographic group, Clearview AI’s accuracy was higher than 99%.

Clearview AI’s software was recently responsible for the first judicial exoneration produced as a result of using facial recognition. A man who had spent five years behind bars for a drink-driving related fatality in the US was freed in September. Ton-That was personally invested in the case and rejoiced at the news.

“It is the most amazing feeling ever. You can’t put a dollar value on it. Stories like that are what really keeps us going as a company,” he says.

From Canberra to Silicon Valley

Ton-That was born in Melbourne in 1988 and went to primary school in Melbourne’s inner-city suburb of Footscray. His mother is a nurse from Tasmania, which is where she met his father, Quynh-Du Ton-That, who ar-rived in Australia from Vietnam at the age of 18 on a Colombo Plan scholarship. Ton-That senior is a literary translator and taught his children about books and art, but they were never pressured into chasing good grades. The family did not have a television at home and Ton-That still doesn’t have one.

Ton-That has been obsessed with technology for as long as he can remember. At the age of six he started typing commands into an early IBM computer at his father’s office at Monash University where his father was a professor of Vietnamese language studies.

“I remember being happy to go to my dad’s office because he had the internet and we didn’t have it at home,” he says.

Early on, he also displayed an unusual aptitude for pro-longed concentration.

“If he developed an interest in anything, he would remain interested in it for years,” says his father.

When he was two, Ton-That developed an interest in a particular piece of Vietnamese music. Every day without fail, the first thing he did was to listen to the cassette tape.

“He would sit and listen to the classical music until the end, and then he would turn to the other side. Thirty minutes one side, then 30 minutes on the other. He did that for about nine months.”

The family moved to Canberra when Ton-That was 10 after his father secured a position at the Australian National University (ANU). Ton-That was excited that their new home had internet. He completed all his homework on a Wednesday and spent the rest of the week building programming skills or playing sport.

At 18, he started his first company making apps. Unable to find investors, he dropped out of his computer science degree at ANU and moved to San Francisco. The university department head called his father in for a meeting.

“Hoan was doing extremely well in the computer science program when he decided to go to America,” says his father. “The teaching staff wanted to keep him here until he graduated and offered to give him a special program. But Hoan said that things change all the time, and that if he left it for another three years it might be too late. He was determined to go.”

Ton-That immediately felt at home in Silicon Valley.

“For me, it was a really cool place because you could say you were working on a new idea and no one thought it was weird.”

But he also had to grow up quickly: he was still running the app-making business, hiring staff and pitching it to investors. His first investor was Indian entrepreneur Naval Ravikant, an early investor in Twitter and Uber.

Ton-That also did some modelling on the side. When he was 19, a rep from the prestigious modelling agency Ford Models asked him to join its books.

“I had no idea who they were,” he says. “I didn’t follow up with it. Modelling is not my thing. Doing nothing is exhausting,” he says with a laugh.

The iPhone games that Ton-That spent hours developing failed to gain traction, and after eight years, the shine began to wear off Silicon Valley. The budding entrepreneur’s artist and musician friends had been priced out of the real estate market, and the valley was full of techies.

“I crashed on a friend’s couch one night and when I woke up in the morning there was someone standing there asking me, ‘What’s the valuation of your company? How many employees do you have?’ It’s a very singular place.”

Future focused

Is Clearview AI one of the most misunderstood companies in the world? “Absolutely,” says Ton-That.

But he senses the tide is beginning to turn. He says the “tone softened” following the US Capital Riots of 6 January because the FBI used Clearview AI’s database to arrest those involved. Ton-That has faith that, in time, his technology will be widely adopted, and he is willing to ride out the storm until that day comes.

“When people see it for the first time, the ‘wow factor’ takes over”

– Ton-That

“There’s always concerns with new technology. The word processor was controversial because people thought it would put typists out of work,” he says.

“I love creating and building things. When I was making games, I remember thinking ‘Wow, people have played the equivalent of 200 years of my game. But what did that mean? Is that 200 years of their lives gone? But this connects me to something that’s rewarding. I’m glad to have this kind of impact.”

Ton-That timeline

1988: Ton-That is born in Melbourne’s Footscray

2006: Ton-That started his first company

2007: Ton-That dropped out of university in Canberra and moved to San Francisco in California

2016: Ton-That moved to New York

2017: Ton-That founded Clearview AI

2020: The New York Times runs a front-page article on Clearview AI with the headline, ‘The Secretive Company That May End Privacy as We Know It’

2021: Clearview AI is found to have breached Australia’s Privacy Act and is ordered to delete its database.