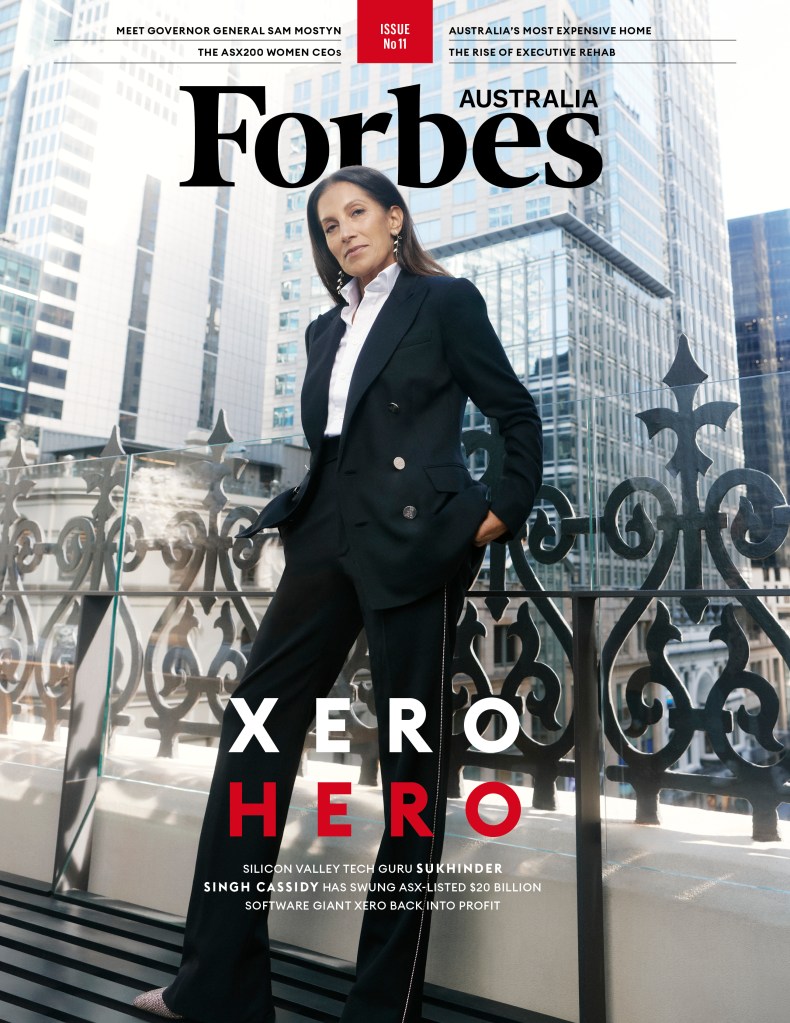

Xero’s Sukhinder Singh Cassidy on the hustle, the big bets and the hard decisions that took her from Tanzania to Silicon Valley, where she still lives while running the fourth-largest tech company on the Australian stock exchange.

This article is featured in Issue 11 of Forbes Australia, on stands Monday, 17th June. Tap here to secure your copy.

The Great Tech Layoff is casting its pall worldwide when Sukhinder Singh Cassidy faces her first all-hands meeting as accounting software giant Xero’s new CEO.

She is in person at the Sydney office in November 2022. The once high-flying firm’s share price has more than halved in the previous 12 months. First question: “Are we going to do layoffs?”

It would be easy to tell the 4,000-odd “Xeros” how great they are and what a wonderful company they’ve built over the previous 16 years to become the fourth most valuable tech company on the ASX. And, how they’ve done it without sacrificing their values.

Or blame outgoing CEO Steve Vamos.

“But I was just like, ‘Wow! How disingenuous would it be for me to arrive here and tell people things are great and then, halfway through my first year, drop a hammer?’” recalls Singh Cassidy in a Zoom conversation. “Some people might say that’s kind. I would say that’s inauthentic and actually not in service of people.”

She has the conversation with Vamos – and Vamos confirms it to Forbes Australia – that if they are going to do it, it will be on her. “It was unfair to put that on the outgoing CEO. ‘If I’m going to drive this decision, I will own it. That shouldn’t be on you.’”

The truth is, she doesn’t know if there will be cuts. The numbers need crunching. She knows from experience that the decision will be easy. The execution is the hard part.

She’d remember the first time she had to make such a call – the tears in letting go some 300 members of her Silicon Valley team at Yodlee in the wake of the 2000 dot-com bust.

It’s been a remarkable journey for the 54-year-old, taking her from her birthplace of Tanzania to Canada, London and on to Silicon Valley to be in start-up land in time to witness the Nasdaq’s remarkable rise and fall of 1999-2000, and to grit it out over the next 20 years of up, down, up. She was at Google and Amazon when they were small. She founded three companies, led two others, and reluctantly weighed in to the women-in-tech conversation before starting a for-profit vehicle to get more females on company boards. She wrote a book about taking bets on yourself before backing herself to stay in San Francisco and run Xero – oceans apart from Xero’s ground zero in Wellington and Sydney.

The Kiwi-founded surprise package has attempted to liberate small businesses from the drudgery of the accounts with a cheeky sensibility and a message of inclusiveness to become the 25th largest company on the ASX with a market cap of $20.4 billion.

But in late 2022, the headwinds are howling. The numbers come back. Revenue is up, but profit is down. They’ve lost NZ$113 million. She knows it’s best to do this hard and fast. They’ll cut 800 of the 4,900 staff – 16%. She announces it at her third all-hands in March 2023. “I started with an apology,” she recalls. “I said, ‘This is going to be a hard conversation.’ I’m pretty sure I cried. Not on purpose – just because that’s who I am. I paused for a moment because I just needed to compose myself. Then I went through all my key messages:” It was the first downsize in Xero’s history.

“The most amazing thing is that I end the day with a number of Slack messages from people checking to see if I was okay.” She knows she’s found her people.

It doesn’t hurt that the share price will climb back over $130 over the following year to be again nearing its 2021 highs. The March-to-March financials for the year after the cuts showed revenue increasing by 22% to $NZ1.7 billion as subscribers rose 11% to 4.16 million. The losses were turned into a $NZ175 million profit.

“We’re doing what we said we’d do,” she announces to the market. “We have a focused strategy to win on purpose.”

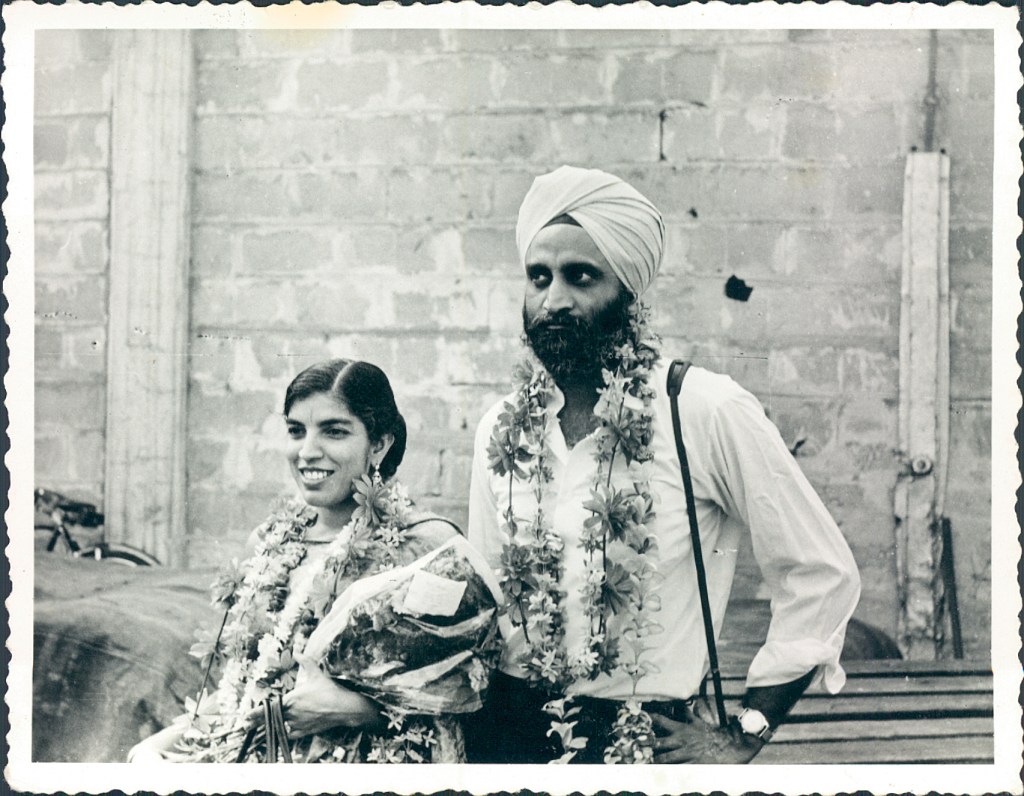

Singh Cassidy talks a lot about purpose. And about her parents. Her mother, Amar Ahuwalia, studied medicine at Lady Hardinge Medical College in New Delhi. While there, Amar was shown a picture of Sukhinder’s future father as a marriage prospect. She rejected him out of hand. He was way too tall.

Her father, Jagmohan Singh, also a doctor, was resisting his own mother’s attempts to marry him off. He was part of the Sikh community in Kenya. He travelled the world and helped put his brother through medical school before, at 40, he caved to his mother’s will and went with her to India to find a bride.

“He met my mum, and she fell in love with him on sight,” says Singh Cassidy. “They married and he moved her to Africa.” They had a medical practice in Nairobi before instability in the newly-independent Kenya saw them move to Tanzania – where Sukhinder was born in 1970 – and apply to migrate to Canada.

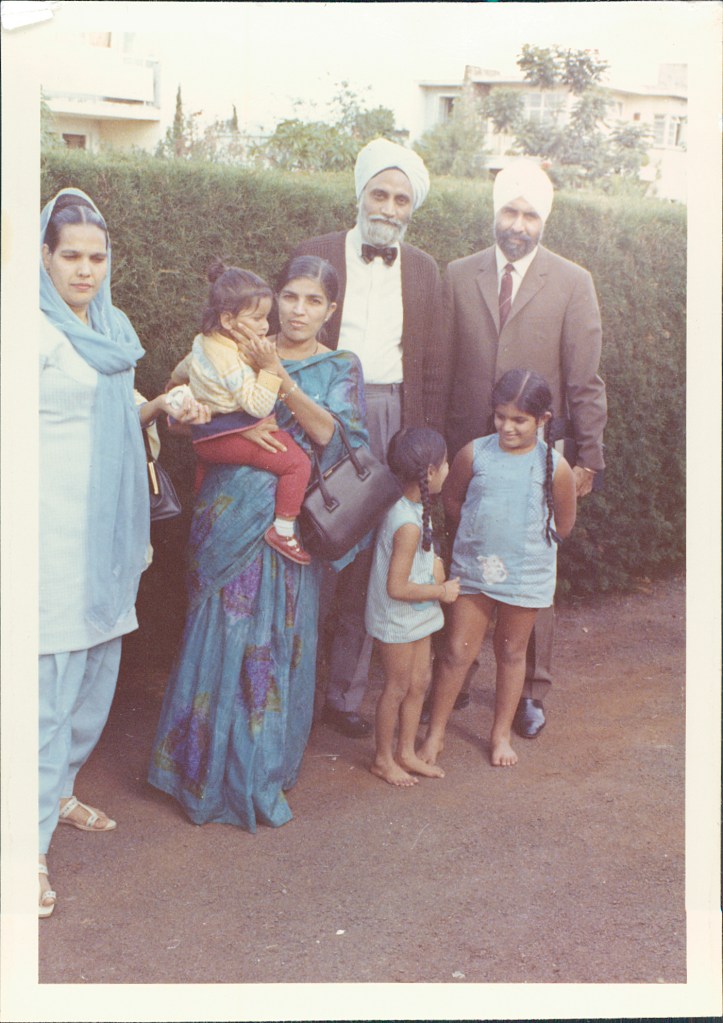

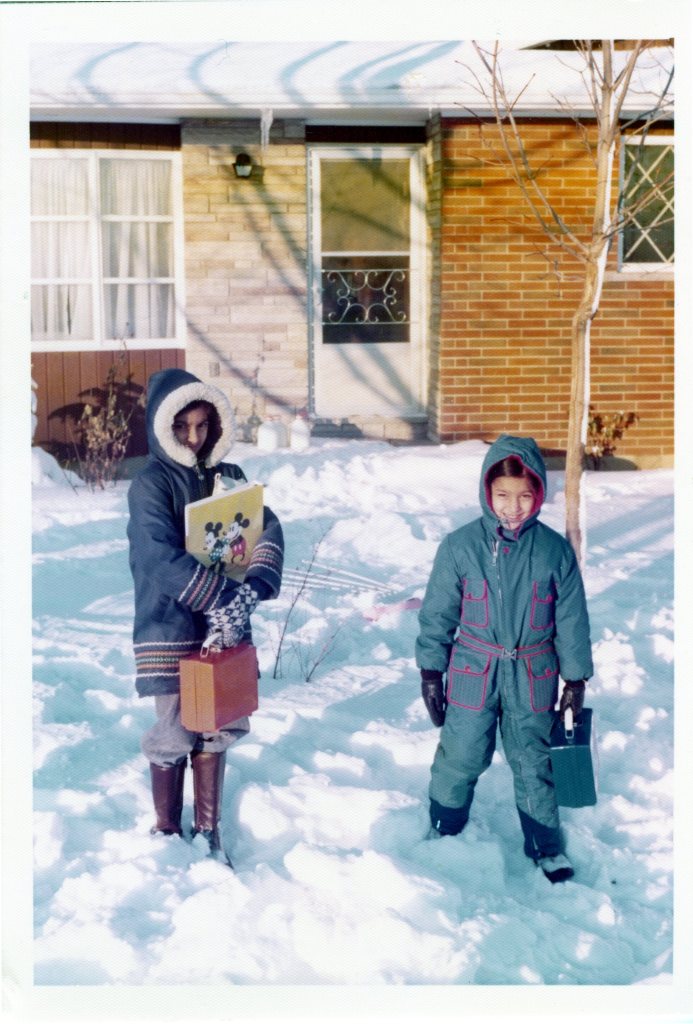

They arrived in St Catharines, Ontario, when she was two. Her earliest memories are from the time her parents were having to requalify as doctors. “My mum is a mother of three, and my dad is late 40s, and they’re starting from scratch. We lived in a really small apartment. My parents did night duty. So, one was watching us while the other was at the emergency. My mum would laugh and tell me about the days my dad braided my hair and sent me to school all askew because she was working.”

She remembers staying overnight at the hospital to be with them. Her parents eventually opened their own practice.

“My dad was the only turbaned person as far as the eye could see,” she recalled. “One of my earliest memories unfortunately – which has really shaped the way I think today about belonging – was being embarrassed to be visibly different. I’m so sad now to think about being embarrassed. But when you’re young, you just want to fit in. We would go to the local shopping mall, and people would call my dad all sorts of terrible names like ‘towel head’ and other things.

“At first, I was embarrassed and then I was mad – my father was my hero. He was an inspiration in all sorts of ways to me. So, that early wanting to conform drifted into wanting to claim my identity. I switched from using my nickname to my real name in college.”

Her father would tell her that her name was given to her by their priest. It meant “princess of happiness”, but she shunned it her entire childhood, preferring her family nickname “Maggu”.

“Who does that?” she wonders now. “Who keeps that strange name over the beautiful, strange name?

“Today, I have a hard time identifying with that person because I’m so proud of my heritage,” she said at this year’s Forbes Australia Women’s Summit. The memory of that feeling informs her values and the types of companies she wants to work with. But more so, her parents informed her ideas about work and service. “I saw two people whose purpose and vocation were the exact same thing. They were both doctors, both very service-oriented, and you could see that they’re living their purpose every day. That is the most seminal thing about my growing up.”

Perhaps the next biggest thing she got from her hero Dad was his love of being a businessman. He was, however, hopelessly disorganised – always running late. He’d spend an hour with a patient on a 15-minute appointment.

Tax day was March 31, and on March 1, every year, he would bring out the shoe box of chequebooks and receipts, spread them on the dining table and recruit his daughters. Every night for the next month, they would grind it out, handwriting the cheque name, number, category and totals into the ledger till they raced to the post office on the night of March 31. It did not instil a love of small business. She studied business at the University of Western Ontario, thinking she wanted to be an executive, whatever that was.

“She’s a pretty intense person. She can be very intimidating to a lot of people.”

Dave Huff, director of strategic partnerships, UPshow

What the annual tax grind did achieve, she says, is take away any illusion of glamour in entrepreneurship. She knew it was a slog, knew it was a numbers game – money in, money out.

“It taught me that my parents just worked really hard. Like, that’s it. Life for them was church, children and vocation.”

Scaring the secretaries

Singh Cassidy went to Wall St to work for Merrill Lynch, which sent her to London where she worked as an analyst before leaving for the British pay-tv operation BSkyB, also as an analyst.

Her London flatmates were American, two of whom were moving back to California, so she went to visit and fell in love with the Stanford vibe and the weather. And the whole executive thing was starting to leave her cold. She found a “craving” to pursue that entrepreneurial thing her father had imprinted on her psyche. So, she moved to California and did a couple of job interviews in the television industry in LA, but felt the pull of this dot.com boom going on in San Francisco. She drove north and slept on the couch of her friend’s parents.

She was hired by Open TV to do something called business development, but all she seemed to get was menial work. On her second day, she was walking to the parking lot with her boss, a middle-aged guy. “And he’s like, ‘Sukhinder, you’re like the rookie on the football field that we just need to coach.’”

She didn’t know what to say. “Coached on what?”

“You scare the secretaries.”

She never got an explanation. She knew she was intense, but she’d watch her boss reward “pretty volatile behaviour” by the men around her. She was miserable and would cry every day. She knew she wasn’t going to get on at Open TV and began to think she wasn’t cut out for Silicon Valley. Maybe it was time to go home.

Then a recruiter called about a job at a company called Junglee which had been started by a couple of Stanford PhDs. Their tagline was “the internet is the database”, which sounded like jibberish to her.

“So I went into an interview with the founders of Junglee, who, to this day, are some of my dearest friends and mentors. They’re all Indian.” They had just brought on a new president, Ram Shriram, who was already somewhat famous as a vice president of Netscape (and who went on to be one of the first investors in Google and remains on their board. Forbes now values him at US$2.8 billion).

At the interview, they explained that they’d built technology to scrape content off the web and repackage it so the user could, say, compare the price of a book at different bookshops.

“I’m not that excited about the internet being the database,” Singh Cassidy recalls, “but I am like, these people are smart, they’re super straight shooters, and I am miserable. So I said yes.”

They hired her as a product manager, but on day two, she got pulled in and told Yahoo had just signed a deal with them to do comparison shopping. “Now we need deals with retailers. So, while we hired you to be a product manager, will you please become a business development manager? And I’m like, ’Okay. So what does that entail?’” And they say, ’Well, you need to get on the phone and call retailers and convince them to pay us if we send them any leads that turn into sales. That’s the business model.’”

It seemed strange to her that anyone would pay to have their own data lifted and compared to a competitor, but she got on the phone and did it.

“Six months later, Amazon says Jeff Bezos has this idea that he wants a marketplace on Amazon where different retailers can present their goods,” says Singh Cassidy. “And he thinks he needs technology for that marketplace. And Junglee’s looks pretty good. And he loves the fact that we have deals with retailers.” Amazon buys Junglee for a reported US$180 million. It’s late 1998, and Singh Cassidy suddenly finds that she’s an executive at Amazon, an online bookshop boom stock that is long on promise and short on profit.

The “negative-to-positive experience” [from Open TV to Amazon] is ingrained in her psyche. “I learned that following smart people who are transparent is great. I learned I could do ‘bizdev’. I learned what I’ve always learned in my career: go where your values fit, go where your strengths are valued.”

‘She blew us all away’

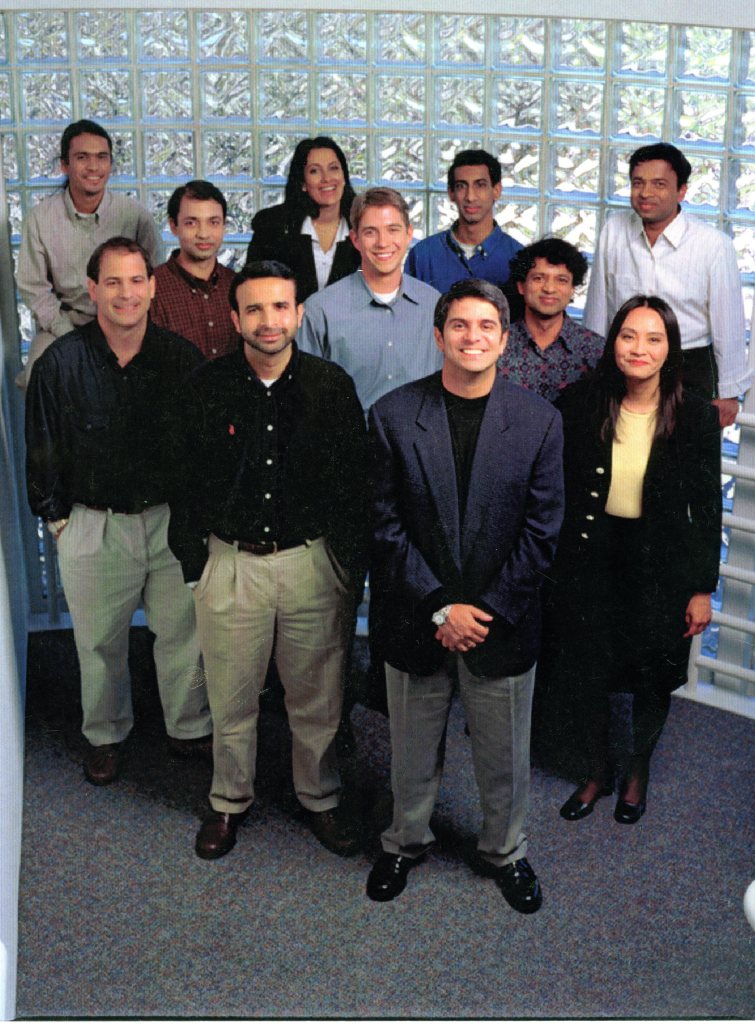

Schwark Satyavolu was a 21-year-old engineer in the process of co-founding a company, Yodlee, to build his idea of taking data from customers’ various favourite websites and aggregating it into one spot. It was 1999. The internet’s bucket of promise was being filled with exuberance and cash.

He and his co-founders, an IT professor and a fellow engineer, needed a business lead. The Junglee founders, fresh from their Amazon exit, were among Yodlee’s first angel investors – and when Ram Shriram was asked for advice on a business lead, one of his first suggestions was Singh Cassidy, who reported to him at Amazon.

“We talked to her, and she kind of blew all of us away,” recalls Satyavolu. “What was most striking was she knew what she thought the company needed. And she had a tremendous level of confidence that she could get it done. She said, ‘Look, I’m the best at what I do, and I should be compensated appropriately.’”

She was prepared to back herself – offering to take a lower salary for more equity and co-founder status. “There was a certain amount of confidence that she could do what it took to make us valuable,” says Satyvolu. It helped seal the deal.

She soon got to work. “Hustle is her middle name,” says Satyavolu. “Everything she does is hustle.” And he means that in the nicest possible way. She put together a PR team, and soon articles on dot-com up-and-comers were talking about Yodlee and Google in the same breath. “That visibility was all generated by what Sukhinder put in place,” says Satyvolu. “We got almost a million users within the first year with zero marketing.”

Singh Cassidy, 29, was one of the oldest in the company. She felt the euphoria. “You’re doing all these things for the first time, and everybody’s courting you, and money’s coming easy. Yodlee raised $15 million in its first round, which today would be considered tiny, but in our day, it was a lot of money. It’s flush with cash.”

The board wanted an older head to come in as CEO and chose Anil Arora, 40. “On his first day at work, he came into the office and literally tripped over me,” says Satyavolu. “I was sleeping in my cube, and my sleeping bag went across the doorway.”

Arora recalls that about a third of the 50-odd employees listed the office as their permanent residence. “The highest energy point of the day was typically midnight when we’d bring in pizza as fuel to keep people going,” Arora says.

Singh Cassidy had an apartment in San Francisco’s Mission District. She got a letter from the postman saying they were going to stop delivering because she didn’t empty the box. “I was never home. I was travelling. I had this biz-dev team that grew from one to 30 – it’s just like everything is yesterday. Everything is possible. You’re innovating. We’re not sure if we’re going to be consumer or B2B. We’re hiring like crazy. We’re spending money at a pretty fast clip and we’re doing deals. We buy a competitor. It’s just go, go, go – until the crash.

“The only things that saved us is we had a lot of customers and a lot of money in the bank.” But not enough to last. “Within a month, you’re laying off, like, 300 people. I cried when I laid off my team, I’m about 30 years old. All these people I hired, I bring them in a room, and they trusted me, so the whole thing was very personal. I’m an owner for the first time, and it feels amazing. And then it feels just incredibly dark. It was everything you might expect.”

Lessons learned from that: “Number one, be an authentic leader, tell people like it is. Yodlee taught me that. It’s okay to show up and be upset. It’s okay to show up and say something bothers you. It’s okay to show up, and if you have to cry then cry, like, none of that gives me shame anymore. People value authenticity. Luckily for me, stylistically, I find it hard to be anything but authentic. Number two, what Yodlee really taught me is to act like an owner. Treat everything like it’s yours. I mean like ‘yours’ in the best possible way and the worst possible way.”

When the bubble burst, Yodlee flipped to a business-to-business model, and Singh Cassidy was suddenly doing deals with the behemoths of Silicon Valley – the largest website, AOL; the largest search engine, Alta Vista; the “next big thing”, Excite. She got them all. “We punched maybe 10 levels above our weight class,” says Satyavolu. “All because of her hustle.”

Arora would remember about a year after he joined, the bubble was still deflating, but interest in where this internet thing was going remained high. They were invited to address a conference of 5,000 bankers and financial industry types in New Orleans. He couldn’t make it because he was closing an acquisition so Singh Cassidy presented for the mostly older men who didn’t have much idea about technology. “The next day, I caught up with a bunch of bank executives, and every second person I met said, ‘Wow! Who is that running development for you? She was awesome.’ Even today, I’ll run into folks who’ll remember it.

“No matter what role she had, it was the most important role in the company in her mind – even though it wasn’t. She was like fight, fight, fight for resources, for the attention necessary for her division to succeed.”

Daniel Alegre, former CEO of Yuga Labs

“She had a dramatic flare that could communicate in such an effective way … Being able to share a vision of how digital experiences were going to change the industry was not common, but it was something people were interested in hearing.”

Around the same time, Arora was in Paris, about to go on stage to deliver a keynote to a similar conference, when he got a call from Singh Cassidy who told him that one of the largest banks in the world wanted to sign a deal with them, but they wanted to do breakfast in New York tomorrow before they’d ink it.

It was early evening in Paris, and Arora assured her they could do it when he returned: “Let me give the speech, and we’ll chat and see if we can reschedule.” But Singh Cassidy was insistent.

“I need you to find a way to get back here by 8 am.”

Arora didn’t want to come, but … “She had a lot of hustle – a lot of belief in herself. We were a small company with limited funding. The only way I could make breakfast was to fly the Concorde. We made an executive decision that it was worth the US$4,000. I got in just in time for breakfast, and we ended up signing a company-making deal. That’s who she is – aggressive. She has a clear vision of what it takes to succeed and has the energy and passion for making it happen. I don’t know we would have had a fraction of the success without somebody like Sukhinder.”

Banging the table

Yodlee survived but faced a long, hard grind (Arora stuck it out and eventually negotiated a US$590 million sale to Envestnet in 2015, a deal in which Singh Cassidy had equity).] In 2003, Ram Shriram – who was on the board of both Yodlee and Google – rang Singh Cassidy and tried to convince her to come to Google, she says. “And I’m like, ‘Google’s too big. It’s 1,000 people.’”

It took months, but she left to join the growing search institution. One of her colleagues there, Daniel Alegre, joined Google soon after. He was running partnerships for Asia and Latin America. In contrast, she ran “Local” – the as yet un-launched feature that would take you to nearby businesses with opening hours, phone numbers and website [Launched March 2005].

“Within a few months of joining Google, she was already an up-and-comer,” recalls Alegre in a phone call from New York. “No matter what role she had, it was the most important role in the company in her mind – even though it wasn’t. She was like fight, fight, fight for resources, for the attention necessary for her division to succeed.”

She raised her hand to lead Asia and Latin America and got the job, so Alegre suddenly found himself reporting to her. “To be honest, I was nervous when I heard. She came across as rough and abrasive. But my concerns were very quickly dispelled, and I realised, no, she was actually just a vocal woman. It was easy for men to interpret that as abrasive … but in reality, she was just a very driven and obviously a very smart individual.

“She ended up being one of the best people I’ve ever worked with in terms of interpersonal relationships and building trust and a cohesive team environment,” says Alegre.

When Google floated on the Nasdaq in August 2004, it only had 12 staff in Asia, most of them in Sydney. Europe was getting all the attention, says Alegre, but Singh Cassidy made a point of getting the founders to pay attention to “Rest of World”.

“You’ll be sitting with her in a meeting, and she’ll have three scenarios in her head before going in. She’s playing three-dimensional chess.”

Ido Leffler, former Joyus board member

“She and I worked closely together to get [Google founders] Larry [Page] and Sergey [Brin] to visit the region and invest in establishing a presence in China.” Alegre opened operations in China. “That was just her grit. She made sure that the leadership understood what the opportunity was – she kept banging the table, till it happened.”

Google was still small enough that you could get time with the leaders. “She had a pretty good working relationship with them,” says Alegre, “they trusted her insights and intuition.”

And she was successful at getting strong personalities to become team players, says Alegre. “When you have all type-A personalities, it’s easy to get into a disgree-and-don’t-commit environment, but she was adamant in forcing a disagree-and-commit ethos for our leadership team. As a result, there wasn’t much backstabbing. People who were on her team went on to have strong careers.” Alegre became president and chief operating officer of Activision Blizzard, then CEO until this March of Yuga Labs, famed for its Bored Ape Yacht Club NFT.

The pipeline of possibilities

Google, though, began to wear Singh Cassidy down. “It’s gone from 1,000 people to 40,000, and all I’m doing is keeping my elbows out,” she says. “That’s not a happy place for me. Politics is a fine thing to deal with if it’s 10% of your job. If it’s 80%, that really drains me. It doesn’t fill my bucket.”

One thing she learned from the Google founders was the notion of creating a “pipeline of possibilities”. So when she felt it was time to leave she made one for herself. She’d been fielding calls for years with job offers. She knew she wanted to be a CEO, she wanted to be an entrepreneur, and she wanted to be in e-commerce.

“When I’m ready to leave, I go to a venture capital firm, and I look at a bunch of e-commerce deals. I take time talking to people about being CEO so I can generate a lot of possibilities. Ultimately, I pick a company called Polyvore which was an early, early version of Pinterest.

“It had a lot of pattern recognition and a lot of brilliant engineers. I knew how to work with brilliant engineers. They needed someone who could generate revenue and a strategy. I knew how to do that. They had been approaching me when I was at Google. I’d studied the landscape, and they came calling for a third time, and I was like, man, I’ve now looked at 20, 30 e-commerce companies. This is the one.”

She took the job and six months later was unemployed.

“This was my first CEO job, and I failed,” Singh Cassidy told the Forbes Australia Women’s Summit in March. “I failed because the founder and I saw the world differently, and although we are very matched IQ-wise, I don’t think we were very matched emotionally.

“It was years before I could talk about it without crying. It was my first CEO job, and I failed. At the time, I thought no one would ever want to hire me again.”

At Polyvore, she’d seen the value of content in e-commerce. “Content that’s shoppable.” She could see girls on YouTube pulling out their shopping bags and showing them to people. “I have a conversation with a VC, and we’re talking about shoppable commerce, and I’m like, ‘Why is nobody doing video?’” Why was nobody taking on Home Shopping Network online? Why wasn’t YouTube adding a shopping cart?

“It seems so obvious that it’s a billion-dollar idea because I had the data points from Polyvore. And I see what’s happening on YouTube. I put those two heads together, and I start working on the idea.” She was still feeling scarred by the Polyvore experience, but she couldn’t leave the idea.

So, she started Joyus with the aim of adding short videos to shopping carts. Instagram video didn’t exist. Pinterest had only launched a few months earlier. “We built a business to US$20 million in revenue – which is good for a start-up. But it took US$50 million in capital to do it. In 2016, people still didn’t believe in video commerce, which is shocking, because maybe circa 2018-19, Instagram starts to boom on video and shoppable content really does come to the internet. It’s just many years too late for me.”

She brought Australian Ido Leffler onto her board, and he remembers her tactical thinking. “You’ll be sitting with her in a meeting, and she’ll have three scenarios in her head before going in. She’s playing three-dimensional chess in terms of the selling side to make sure that she gets the outcome the company needs and that it makes sense for the people she’s selling to. She’s a win-win type of CEO, not win-at-all-costs. She’s a fun person to hang out with, too.”

Singh Cassidy sold Joyus to StackCommerce in 2017 for what TechCrunch reported to be “less than US$50 million”.

America’s top ticketing marketplace, StubHub, offered her the CEO role. Dave Huff had worked for Singh Cassidy in media partnerships at Joyus, and she asked him to join her at StubHub. “She’s a pretty intense person,” Huff says of his old boss. “She can be very intimidating to a lot of people.”

He always got on well with her, he says, but “I could tell that some people were nervous about screwing up in front of her”.

“I felt she was a better big-company CEO than a start-up CEO. She’s more like a battlefield general than a special-forces platoon commander. She’s really good at seeing the big picture and inspiring big groups of people with a brilliant vision.”

An example, Huff says, is the way she made sure everyone was “rowing their boats in the same direction”. “She never wanted people to be able to say that they didn’t know what the company plan was or what the leaders were thinking. So, once a quarter, everyone would get a flyer on their desk – a one-pager that was beautifully printed out – ‘This is what we’re doing this quarter’. It would be the same message at the all-hands meetings, and the same thing would come via email.” He on y realised how effective it had been after she left, and the new leadership were not as transparent. “The difference made her stand out.”

Singh Cassidy took the eBay-owned StubHub through to a $US4.05-billion sale to Swiss ticket seller Viagogo in early 2020, a month before COVID-19 shut down every single gig on their books. “The proudest thing about StubHub for me was just navigating that crisis,” she says. “We restructured and took the burden of the company down 70%. Then I turned the company over to my successor.”

She started writing the book she’d been itching to pen for years, Choose Possibility: Take Risks and Thrive, Even When You Fail, about the notion of creating that pipeline of possibilities and how to weigh them up against each other.

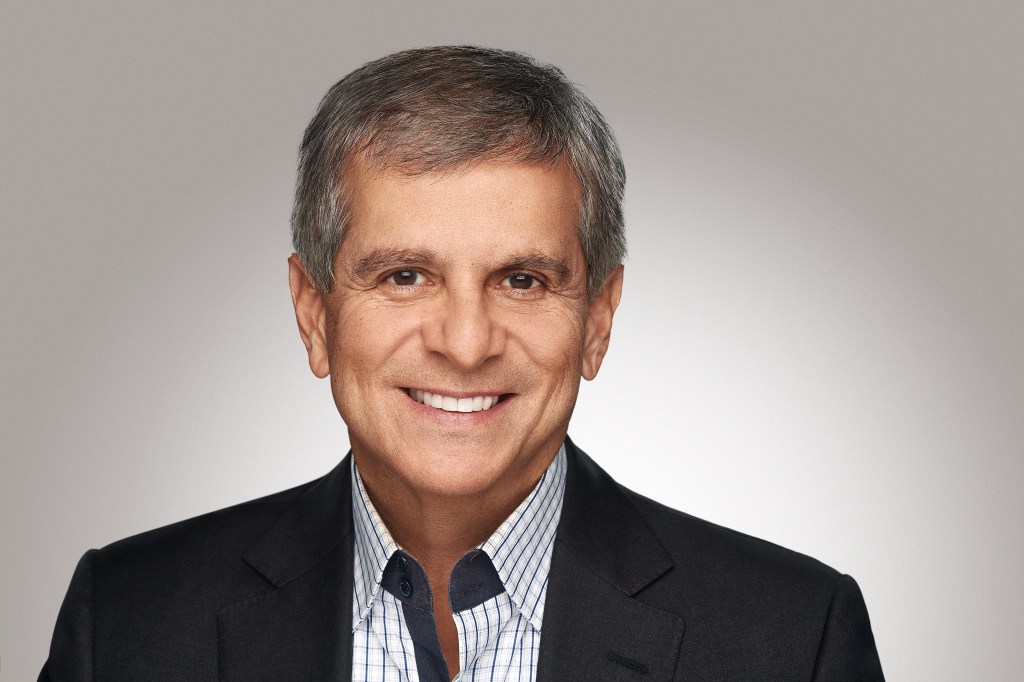

After launching the book, she “parked herself” at a venture firm, started investing, helped raise a fund that had a diversity element to it with Acrew Capital, and job searched. “And then I found Xero, or Xero found me”.

Xero founder Rod Drury recalls being struck by Singh Cassidy’s blend of urgency and warmth. “The first few times I met Sukhinder, it never felt like an interview,” he says. “It was more sharing ideas and stories with a fellow entrepreneur. One of my favourite moments was watching her quickly get how big the opportunity was and seeing her brain go to work. I think we both knew then she had to come and lead our team at Xero.”

“So, I was, on the one hand, feeling pretty empowered and, on the other hand, pretty disgusted by the stories I was hearing. I’d never used my voice on gender. “

Her former Joyus colleague Ido Leffler is certain Singh Cassidy was recruited for her steady hand and governance skills, “but also somebody who could take their initial vision and actually make it bigger. Sukhinder has a real knack to enthuse a hardened soul, to get the blood running in an organisation.”

Singh Cassidy doesn’t think she scared the secretaries this time around but acknowledges there were some tough moments.

“We made some hard changes, like hard – I’m really proud of Xero and Xeros. I think that they are learning that it’s okay to make hard decisions in pursuit of a bigger ambition – as long as that ambition is not ambition for ambition’s sake. I’m interested in ambition for impact. I believe that’s how Xeros are wired. When you speak to Xeros about our purpose, it resonates. If you want to just speak to Xeros about being king of the hill for being king of the hill’s sake, like, that’s not what drives me, and I don’t think it’s what drives this company.”

Let me show you where the great women are: the origins of theBoardlist

“While I’m running Joyus, one of my board members, Keval Desai, complains to me that not enough people are talking positively about what women can do as CEOs,” says Singh Cassidy. “He says, ‘I have five female CEOs in my portfolio, and all anybody writes about is how terrible it is to be a female CEO.’ I start to get irritated that the only stories about women in tech are negative. So, I surveyed a bunch of female founders I know and write an op-ed called Choose Possibility.

“It gets published on Re/Code. It basically just says, ‘Hey, being a female entrepreneur is still pretty empowering. And by the way, all these women say that these issues with discrimination and harassment, they’re all real.’”

Singh Cassidy thought the bottom-up approach of getting more girls into STEM to even out Silicon Valley’s gender inequality was fine, but a top-down solution was also needed. After trying to get a prominent venture capitalist to install more women onto boards, she decided to start her own side hustle. “I’m gonna crowdsource great names. And I’m just gonna launch a spreadsheet called theBoardlist. And I’m going to show you where all the great women are. At Joyus, I felt what it was like to be a female entrepreneur, and I felt pretty privileged. I had Yodlee under my belt. I had my reputation at Google. It was easy for me to raise money. But I was also an angel investor in other female start-ups.

“I was the first investor in Stitch Fix. And Katrina Lake [founder and CEO] went public with how a male VC sexually harassed her. Other female founders would tell me about how they could not go into a venture pitch without somebody asking them about their intentions to get pregnant.

“So, I was, on the one hand, feeling pretty empowered and, on the other hand, pretty disgusted by the stories I was hearing. I’d never used my voice on gender. I just put my head down and did a good job. It became obvious that not talking about gender was a missed opportunity as a leader. That’s why I started theBoardlist. That’s why I wrote the op-ed.

“TheBoardlist grew organically from 600 names on a spreadsheet. Today, we have 70,000 people in our email database and 40,000 members who are candidates looking for board opportunities. We have all types of representation – including white males – but the database is majority diverse.”

She says it is unknown how many board seats have been filled using theBoardlist because it is a discovery platform, and they don’t know the final outcome. “But it would be in the 100s. Maybe 1,000”.

“We’re there to help people get discovered, up a funnel, and to start the matching process. And get rid of that adage from 10 years ago: ‘Where are all the great women?’ I’m like, ‘Let me show you where they are.’”

It’s a “for-profit but mission-driven” company, and Singh Cassidy remains the largest shareholder.

“There’s a mini backlash right now in the US against diversity. Diverse thought creates better outcomes. So, forget the blip. Despite the headwinds, the category keeps growing. The category of board-governance software keeps growing, too, and we sit at the intersection of those.

“The lessons I learned from being a founder at Joyus and Yodlee are applied at the Boardlist.These are: don’t raise a lot of money; don’t get over your skis; stay focused on the mission. Keep it growing.

“I now know the value of being profitable earlier. I didn’t when gobs of money were being thrown at me in previous start-ups. So this one’s run very differently.”

Forbes Women is live now: A supportive community of driven, entrepreneurial-minded women who are changing the world through business.

Xero facts

Despite international inroads, Australia and New Zealand continue to be Xero’s power base, generating revenues of $NZ970 million compared to $NZ744 million for the rest of the world, according to the company’s recent report.

In Australia, Xero increased subscriptions by 205,000 to reach 1.8 million. New Zealand added 38,000 net subscribers to reach 605,000.

They added the same number – 38,000 – in North America to reach just 422,000 subscribers, indicating the size of the challenge and the opportunity across the Pacific.

And 107,000 subscribers were added in the UK for a total of 1.1 million there.

Jarden analyst Tom Beadle was cynical of Xero’s valuations two years ago when it was worth upwards of $150 a share. “Back then, they hadn’t demonstrated that they could produce meaningful cash flow. This result puts that argument to bed,” Beadle says.

The highlight of the results for Beadle was that it beat its guidance on operating costs – with it being just 68% of revenue in the second half of the financial year compared to a prediction of 75%.

After the results, Jarden upgraded its price target on Xero from $141 a share to $144, based on a presumption of continued modest, 10% growth in the US. “But there is asymmetric upside risk [i.e., the upside is larger than the downside] if they are to execute in the US.”