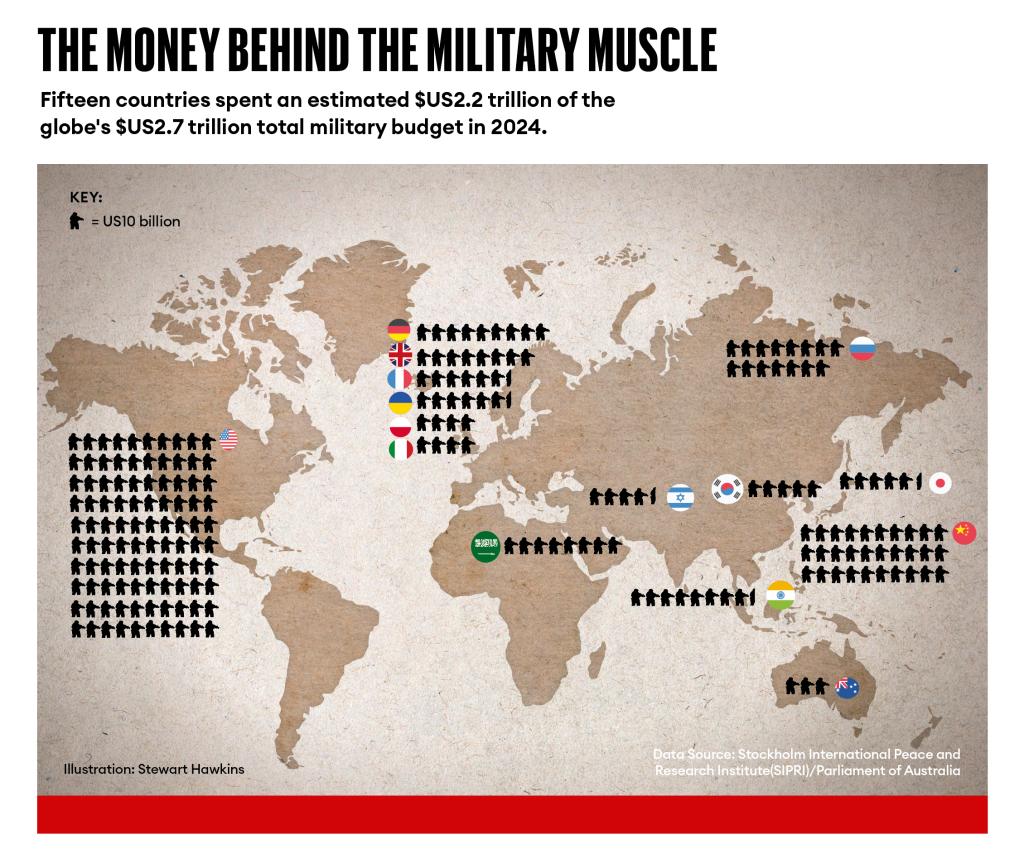

Steve Baxter is betting that weapons are Australia’s most “irrationally unloved” asset class – and that time is running out to lose our ESG fixation … and fix the nation’s lethality gap.

As befits a former Shark, Steve Baxter doesn’t shy away from deadly things. On Zoom calls, an Owen submachine gun and a Black Sky missile sit on the bookshelf behind him – fitting symbols for his latest bet: that lethal defence technology is an overlooked goldmine.

A former soldier, internet entrepreneur, and venture capitalist who has made millions backing companies like ed-tech unicorn Go1, Baxter believes weapons makers are being overlooked for all the wrong reasons, especially the ethical ones.

In a climate where ESG concerns keep big funds at bay, he launched Beaten Zone, which, as Vu Tran, co-founder of Go1 and now missile-maker Black Sky Industries says, is the only venture fund in Australia that will openly touch things that go bang.

“There are a lot of funds that will invest in defence-tech, but he’s the only one to invest in lethality,” Tran told Blackbird’s Wild Hearts podcast in June.

Tran has trodden the same intellectual path as Baxter, leaving the $3.3 billion education platform Go1 to solve the problem of Australia’s lack of sovereign defence capability. He teamed up with missile maker Blake Nicolic to co-found the missile maker Black Sky, which Baxter describes as “Australia’s most lethal company”.

Baxter tried to invest in Black Sky, but they don’t need the money, he says with a mixture of regret and respect, but Tran returned the compliment, investing in Baxter’s Beaten Zone, which has raised $12.3 million.

“We’re an anti-ESG arbitrage fund,” Baxter tells Forbes Australia, explaining the money side of his passion for defence start-ups. “ESG [Environmental, social and governance] scares all the money out of the market: fewer investors equals better price for equity. That’s the essential dynamics.

“As everyone realises that defence companies aren’t evil, that they’re actually necessary, that discount for lethality will lessen over time, which should be good for our portfolio.”

But for Baxter, having made millions backing almost 100 start-ups over the last decade, this moral and financial crusade is taking him back to his military roots.

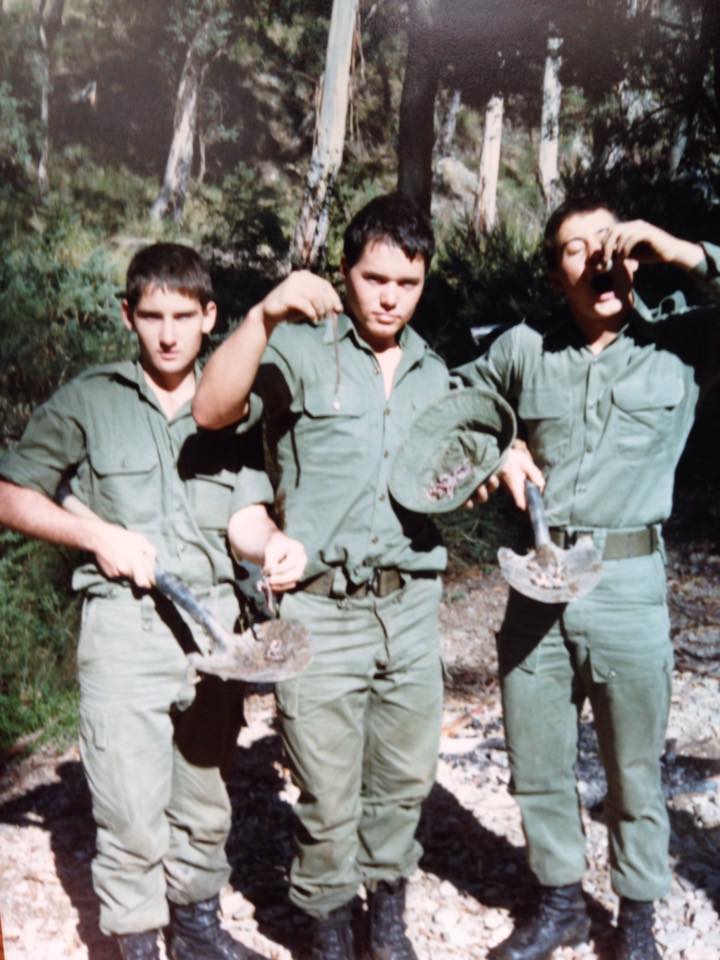

Boy soldier

Baxter joined the Australian Army when he was just 15, in 1986 – a time of relative peace and stability. He might never have left the military had the world been a little more dangerous. “If I’d been able to deploy overseas, my career would be a lot different,” he says. “Because that’s what I joined up to do.”

The army trained him in electronics. While his CV can say he was a guided-weapons technician, he was doing everything else, too, from tank turret hydraulics to telecoms.

“We didn’t have as much stuff as they do now, and we had nowhere near the budget. If something broke, you had to wait 11 to 12 months to get the part. It was a boring army.”

He started his first business installing dial-up internet services while still serving in Adelaide.

“I had a really good boss, and my business was going well, so he let me discharge four months early. I’d signed up for nine years and didn’t quite get there.”

That business, SE Net, grew to 70 staff and 37,000 customers in five years, before he sold to OzEmail.

Moving home to Brisbane in 2001, he started another business, PIPE Networks, with an old school friend, Bevan Slattery. They floated it on the ASX in 2005, and a few years later, Baxter left the company for a job at Google, building high-capacity networks across North America.

“I don’t understand how defence isn’t carved into ESG, but ESG don’t like us, we don’t like them, so we sort of call it a draw.”

Steve Baxter

Baxter still had a stake in PIPE when it was taken over by TPG Telecom Ltd in a $373.09 million deal. “I would have liked to have stayed in California longer, but it had quite a punitive taxation regime, so it was best I wasn’t there.”

He told his wife, Emily, he wanted to take a quarter of what they’d earned in their various exits to invest in start-ups. “Oh yeah, we can afford to lose that,” she said.

Thanking her for the vote of confidence – and her correct attitude to angel investing – he got on with it.

He doesn’t like the word “angel” with its implicit superpowers, but he managed to soothsay some winners out of the “96 or 97″ companies he’s backed since returning to Australia. Their venture company, TEN13, has made a 29% internal rate of return, he says.

Tran’s Go1, now sitting on a $3.3 billion valuation, was an early investment that Baxter is still in. His best exit, he says, was DoseMe, a Brisbane-based software platform for the dosing of potentially dangerous drugs. “We ended up exiting that business for about 24 times our money.”

“You cannot get insurance. You cannot get finance. There are huge barriers to having an actual defence company.”

CEO DefendTex

Other notables include Clipchamp [sold to Microsoft], Car Next Door [sold to Uber] and Atomo Diagnostics [listed during the COVID-19 share spike].

After two years as a Shark on Network Ten’s Shark Tank, Baxter was invited by the Department of Defence to help with its innovation plans in 2016.

“They opened the tent. I looked inside and it was just fantastic what they were doing,” Baxter says. “There is a lot of capability being created through the private sector with government and defence grants. But it then sort of falls into the valley of death.”

He saw the opportunity and decided to put a portion of TEN13’s money into defence. “But when I stood knee deep in the market, I understood how much deal flow there was and how much opportunity there was. The three or four million bucks a year I was going to put to this wasn’t going to touch the sides.”

In late 2022, Baxter established Beaten Zone as a specialist defence fund, named after the part of the battlefield where bullets are hitting and shells are landing.

He threw in $6 million, with the intention to go to $20 million by the time the fund reached his target of $60 million. It is currently up to $12.3 million raised with a staff of seven. They’ve made three investments totalling $4.5 million.

No mainstream funds have opted into Beaten Zone because, Baxter says, ESG parameters rule it out. He sees ESG as a fluffy, first-world concept.

“I don’t understand how defence isn’t carved into ESG, but ESG don’t like us, we don’t like them, so we sort of call it a draw.”

Outrageous statements

But it does help him in the first part of his role – to buy low. “What I do is I find an irrationally unloved asset and invest in that. Because of the concerns around ESG in Australia, there’s nothing more irrationally unloved than a defence asset.

“At the end of the day, you don’t defend democracy with harsh language. You need a robust man carrying something heavy. And we back firms that make heavy things. We don’t like it, but I think we’re about to need a lot of these heavy things.”

In contrast to, say, DroneShield CEO Oleg Vornik, who often feels the need to point out that his systems don’t hurt anybody – that they don’t even hurt the drones they bring down – Baxter has chosen to stand up in the beaten zone of public discourse.

“Many of the people I’ve met in the early days of this journey couldn’t even bank in their business name. They had to bank in their private names. These are people making things for the Australian Defence Force, but they couldn’t open a bank account. Insurance is exceptionally difficult, and credit cards are often impossible to get from these organisations because of the connection to defence.

“So, we’re not going to stand behind these people and hide. We’re going to stand beside them, and hence the name.”

One of Beaten Zone’s first investments was in Sydney-based HEO Robotics. Its co-founder, Will Crowe, met Baxter at a conference in 2022. “I was liking some of the outrageous things he was saying,” says Crowe. “And hopefully I impressed him back with some of the outrageous things I was saying.”

It was soon after Russia invaded Ukraine. Baxter was confronting Australia’s defensive vulnerabilities. “Steve’s seen that before others have. His coming out and talking about that was really important. And also really brave at the time. It has since become more obvious.”

No one at Beaten Zone is entitled to handle classified information, which creates a problem for a business wanting to invest in these opaque spaces, but Baxter will not seek such clearances. “It would double or triple the cost of my business,” he says. “It would make my staff a target, so we don’t get into the secret stuff. We speak to people with classifications and ask them, ‘Would you buy this and fight with it?’”

Baxter is critical of how defence has previously been funded. “I call it funding by Hunger Games – the government had this pot of gold, and everyone tries to kill each other to get to the pot of gold. The guy who builds the miniature submarine thinks he’s competing against the guy who builds the missiles. As a result, there’s very little co-operation and there’s a lot of hatred.”

Beaten Zone’s deal scout, Jake Bostock, has identified 387 companies in Australia that fit their investment profile. They were following 13 closely, until Canberra-based drone-motor company Rotor Lab sold to US-based Unusual Machines in June for US$7 million.

The best businesses are the ones that don’t need the money, says Baxter. “We had 13, now 12, that we really love. Black Sky is one of those. My task is to go to the 12 businesses in our high-opportunity pipeline and understand them. For the most part, these businesses don’t need capital; they’re somewhat cash-flow generative. They’re profitable businesses.

“My job is to – at the risk of sounding cynical – be their best friend, so I can be there with a cheque, ready, waiting to go and warmed up. That day may never come. That’d be great. I love seeing success. I’ll grind my teeth and complain about it, but I’m still pretty happy about it.”

Beaten Zone’s logo features an Owen gun like the one that sits behind Baxter’s desk. He explains that in 1938, the Australian army rejected the ideas of the gun’s 23-year-old inventor, Evelyn Owen.

“He was told to go away. Only gangsters used submachine guns. Then Hitler rampaged through Europe with submachine guns.” The Owen gun was taken on. Tens of thousands were made in Newcastle and Port Kembla, just in time for their use in New Guinea against the advancing Japanese. “That’s innovation done too late. We look at that symbol and say, we have to support innovators. We can’t have something that late ever again.”

Controversial Weapons

Responsible Investment Association Australasia’s co-CEO, Estelle Parker, said consumer research had shown 55% of Australians want to avoid investments in armaments, but arms investments did not preclude ESG certification by RIAA.

Nuclear and “controversial” weapons such as landmines were not allowed to be certified by the RIAA, but others could be, Parker said in an email to Forbes Australia.

Many RIAA-certified funds do hold stakes in companies involved in the production of conventional weapons.

“In these cases, we examine the claims the product is making about its exposure and assess whether or not they are sticking by these claims,” Parker said. “For example, if an investment product seeking certification told consumers that it did not invest in weapons, but we found that it did, we’d require them to divest.”

Australia’s largest insurer, IAG, said in a statement that the defence industry was “generally outside of IAG’s risk appetite and underwriting guidelines, however, we continue to assess providing cover to businesses on a case-by-case basis in line with our Responsible Underwriting Approach and Reinsurance Treaty”.

Getting the memo

Even the Greens are getting on board the sovereign capability train. The peacenik political party promised at the last election to reallocate a whopping $4 billion to domestic defence industries – paying for it with the $77 billion they’d save scrapping the AUKUS nuclear submarine deal.

One of the great beneficiaries of such a policy would be Travis Reddy, an army veteran and CEO of DefendTex, who says his company still needs to keep a low profile. “A lot of what we do is not on our website,” Reddy tells Forbes Australia.

“Every time we put something up, it gets used against us by insurance companies. There are issues with being in the defence industry in Australia and not being a multinational.

“We’ve never sold anything to Israel, as an example, but it doesn’t matter, you immediately get lumped into this idea that people who make weapons are mercenaries who will sell to the highest bidder. It’s not like that. It’s highly regulated. You cannot do anything without Australian government approval on a contract-by-contract basis.

“You cannot get insurance. You cannot get finance. There are huge barriers to having an actual defence company. Most companies that work in defence here are not making the lethality aspect. They make the landing gear or the radar. But other than Thales, a French-owned company, nobody makes the thing that has the lethal effect – that’s why we have no capability to defend ourselves long term.”

DefendTex makes a range of innovative weapons and has been trying to buy a Brazilian missile manufacturer to bring it to Australia, but has had little support.

But Reddy says the big four banks are starting to come around. “They now seem more willing to look at it [defence] than they did in the past. But, insurance and other finance sources have still not ‘read the memo’.”

One defence start-up founder – making a delivery system, not a warhead – said he’d had plenty of approaches from venture capital but hadn’t needed the money because their customers, primarily the Australian Defence Force, were funding their prototypes. “The problem in Australia is that Defence just aren’t buying anything much from our industry,” the founder, who asked not to be named, said.

“So the success stories that attract capital are not being created. We have been fortunate to have something they seem to want – well, enough to keep funding us at least. But even for us, it’s uncertain when that will translate to ‘let’s start producing big numbers’.”

While US President Donald Trump has demanded that other countries lift their defence spending, Black Sky’s Tran says Australia is looking at it the wrong way. “The debate that is often had across the world right now is, ‘What percentage of GDP should we spend on defence? Is it 2%, 4%, 6%?’

“I want to call bullshit on that question. The questions we should be asking are: ‘What percentage of GDP should the defence industry be contributing [to GDP]?’ and ‘How do we make sure that our defence industry forms 2% to 3% of our GDP?’ Think about the job, technology and industry creation, and the benefits.

“If we create an awesome defence industry in Australia, it makes us incredibly spiky, prickly when it comes to anyone who wants to attack us.”

Who is Steve Baxter backing?

- Arkeus Solutions produces hardware that can see in 19 “non-visible” spectrums, then analyse what it sees with AI, enabling drones to do surveillance and reconnaissance autonomously. “Their main product is a hyperspectral sensor, so it’s a very fancy camera,” says Baxter. “They’ve done some very sexy stuff with the physics of detection, which I’m not cleared to understand, but all the military users love it. It’s got a lot of efficacy in and around what they call the littoral space, the space between the land and the ocean. It’s just prohibitively priced at the moment.”

- Zendir has a software platform that allows space companies to design and rehearse space missions of great complexity. “Space is highly militarised,” says Baxter. “We like space. And it’s very well named. Between 300 km low-earth orbit and 500 km low-earth orbit, there are 185 billion cubic kilometres of space. We think there’s a lot of room up there for business.”

- HEO Robotics – A Sydney-based satellite imaging business with a platform that allows the owners of Earth-imaging spacecraft to turn their cameras around and take pictures of other satellites. The CIA’s investment arm, In-Q-Tel, is a major backer. “It sounds inoffensive, but it’s exceptionally necessary,” says Baxter. “The military has an unfortunate term, a ‘kill chain’, which is from the moment you spot something, to the moment you whack it. This is in that chain.”