It could be the ultimate cure for ‘range anxiety’. Will the world of electric cars give battery swapping a chance?

A decade ago, just as the Tesla Model S was beginning to upend the automotive world and before Elon Musk was richer than Midas and still looking for ways to keep the nascent company afloat, he demonstrated a novel idea: an automated battery swapping station that could change out a Model S battery pack in less time than it took to fill a comparable gas-powered car with liquid fuel.

At the time, it seemed like such a service would essentially negate the newly coined “range anxiety” for electric vehicles, for Teslas at least. But it was not to be.

At least, not yet.

For a multitude of reasons – primarily Musk’s decision to focus on creating the now vast network of high-speed NACS “Supercharger” facilities – Tesla did not develop the battery swap system.

Legacy automakers, caught napping on electric cars, commonly referred to as EVs (Electric Vehicles), turned their resources to quickly developing new EVs, leaving the charging issue for later or to be handled by partners.

The result is the U.S. public charging infrastructure remains inadequate at this time, and most EV owners (self included) charge their vehicles at home. But that’s not an option for everyone.

After Tesla’s demonstration, the battery swap idea didn’t die, but it did change.

In Asia, where scooters are used by tens of millions of people as a primary form of transportation, battery swap stations by scooter makers like Taiwan’s KYMCO and Gogoro are quickly becoming more common, and are also on the cutting edge of EV tech.

They could also be pointing the way forward for electric cars and other e-vehicles as well.

Why battery swapping works for scooters

While electric motorcycles are high-performance marvels, they have also come in for deserved criticism for their limited range, heavy weight and long charging times. Conversely, its lowly cousin, the urban scooter, has proven to be the better two-wheeler to electrify in the short term.

Scooters weigh much less than motorcycles but essentially accomplish the same task, while also providing superior utility and ease of use. They don’t have the high-performance expectations of full-size motorcycles, trading speed for a lower price and increased practicality.

Electric scooters are not exactly s new idea. Italian scooter/moto maker Piaggio, which owns Vespa, has offered the Vespa Elettrica for several years now and Swiss-owned Lambretta showed an all-electric prototype, the Elettra, at EICMA last November.

Recently, I enjoyed riding BMW’s sci-fi CE 04 electric scooter, which impressed (see review above).

BMW, Vespa and Lambretta are high-profile brands, but in Taiwan and other Asian countries, lesser-known domestic market scooters makers have had all-electric models widely available for several years.

Charging issues seem to dog pretty much any electric vehicle; but battery swapping programs for scooters seem to have caught on – and the idea is expanding to other vehicle types, especially in China.

The start of the swap

In 2015, Taiwan-based e-bike and e-scooter startup Gogoro began building out a network of self-service “GoStation” kiosks where riders of Gogoro’s electric scooters could quickly and cheaply swap out batteries, extending the scooters’ range to basically anywhere there is a swap location.

Gogoro eventually went public in a SPAC merger in 2021, and now, GoStation battery swap locations are used tens of thousands of times each day in multiple countries, including Israel, the Philippines, Singapore, India and China.

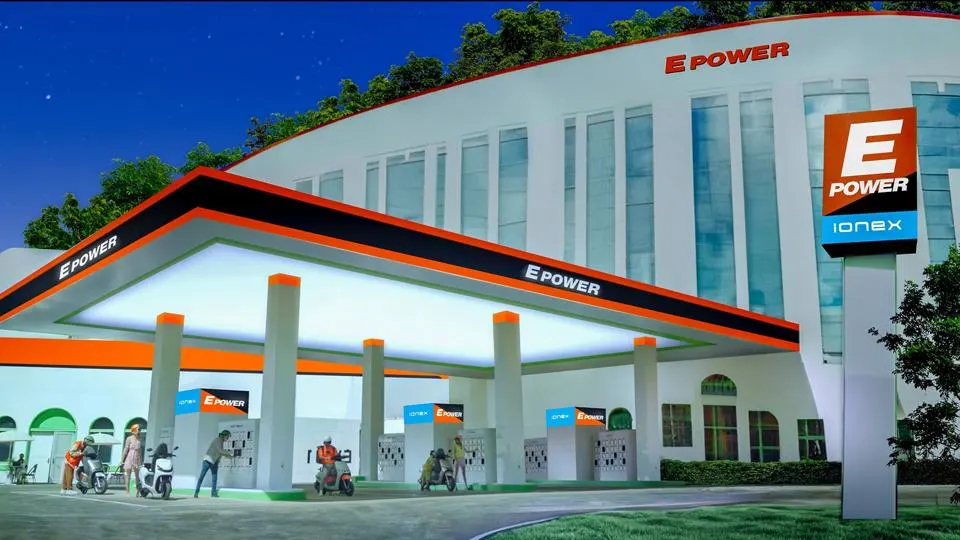

Now, another Taiwan-based scooter maker, KYMCO, a major player in the world-wide scooter market for decades including to the U.S., has updated its strategy around swappable batteries with a new program called iONEX, a venture they initially launched at the 2018 Paris Motor Show.

KYMCO looks to have an ambitious plan in place around both the e-scooters and battery swap stations with the newly updated battery-as-a-service venture.

Indeed, thousands of KYMCO battery swap locations are already in service, but the latest iONEX iteration features new and larger batteries and a simplified swapping system.

Riders use their smartphones to pay a small fee for only the energy used, and it only takes a few seconds to swap out the batteries.

KYMCO has also added plug-in charging points in cooperation with businesses as an added service, as well as the option to remove the battery and charge it at a location that does not have an iONEX kiosk.

The scooters can also charge directly from a wall plug, and KYMCO offers a simple device for charging the removable batteries within the home.

KYMCO also plans to sell the scooters without the “cost” of a battery since the swap system will provide that component, greatly reducing the upfront cost of the scooter for the owner.

Basically, KYMCO has created iONEX to ensure there are multiple ways to keep the batteries charged and scooters moving, even outside of the swapping stations.

And rather than one battery, the sleek new iONEX electric scooters (below) can carry two or more power cells for extended riding range and go up to 60mph. Changing out a spent pack for a fully charged battery or two at an iONEX kiosk typically takes less than a minute.

So far, exact range numbers have not been specified but the swapping strategy essentially renders range concerns moot due to the already large existing network of swap stations in Taiwan, which will continue to grow.

KYMCO also has a financial and technical partnership with American electric motorcycle maker LiveWire, which was hatched by Harley-Davidson in 2019 before it was split off as an umbrella company and went public in a 2021 SPAC deal that involved KYMCO as an investor.

However, at present, LiveWire electric motorcycles do not use swappable batteries, despite a new model, the Del Mar, that uses a smaller battery pack than the original LiveWire model.

KYMCO and Gogoro are also not the only players in the battery swap industry; Japanese motorbike makers Yamaha, Suzuki, Kawasaki and Honda – all of which also produce scooters – have also shown battery swappable prototypes and belong to a consortium looking to implement standardized batteries between brands.

And while they initially indicated the battery swap system would work for motorcycles, the effort appears to now more closely focus on scooters.

Contacted by Forbes.com, KYMCO’s CEO Allen Ko said he was open to working with partners to expand the use of the iONEX battery system, but would not name any specific partners of interest.

With KYMCO already a well-established company, it will be interesting to see how iONEX system fares and how it affects competition with aggressive startup Gogoro and others, or if there will be cooperation between the players.

EV issues: Standardization, execution and monetization

The job of pumping gas into a vehicle has been standardized for so long it’s difficult to imagine it ever had the same issues EV drivers now face, but early in the 1900s, the auto and fuel industry wrested with just that problem.

In the very early days, gasoline – then an almost throwaway byproduct from the creation of the then-do-it-all fuel kerosene – was sold to early motorcar drivers in small containers at stores.

“Filling stations” came along around just before 1910 but it wan’t until 1930 that the dispensing nozzles we are all familiar with were standardized by the government, greatly simplifying fueling.

Comparatively, we are still in the early 1900s of the EV evolution, but hopefully it won’t take decades to come to an agreeable charging standard; Tesla’s NACS standard seems to have the winning hand at this time.

Outside the U.S., despite Tesla’s demonstration, some carmakers are beginning to look more closely at the battery swap idea.

Time will tell how it shakes out since there are a number of issues still to be sorted out in the battery swap market segment, but major Chinese electric carmaker Nio – and Chinese auto giant Geely by extension – is on board and has hundreds if not thousands of swap stations in China for their domestic models.

Information from 2023 indicates that millions of battery swap transactions have taken place in China and the practice is now well established. So why is it not happening elsewhere?

One problem is that most EVs use different battery shapes and sizes, making a simple swap not so simple – a problem echoing the initial fumble on an EV charging standard.

Some battery pack design similarity is occurring with platforms like GM’s Ultium and of course Tesla’s original “skateboard” system, but even within each platform there are big differences from make to make and model to model.

Rapid development of EV battery technology means any standardization is likely many years away, if it is even attainable at all.

The battery in a Chevy Bolt is not the same size, shape, voltage or weight as the battery in a Tesla, Hummer EV or Hyundai Ionic (just to name a few), and as EVs continue to evolve, that is unlikely to change, at least in the U.S. and EU markets where competition rages.

Another obstacle is infrastructure. In China, where public works and tech standardization can be mandated without recourse, battery swap tech has a better chance at flourishing, especially with the already massive and rapidly growing EV user base.

Given the number of people on scooters in China (and Asia by extension), a path to profitability for swapping systems and companies is possible.

In the U.S. and EU, battery swap stations would require huge investments in real estate, robotics, personnel, safety protocols, energy storage and other expensive aspects, and all that for a user base that is only now closing in on a double digital percentage for all electric vehicles on the road combined.

While several automakers have signaled they intend to stop production of gas-powered cars by 2030, 2035 or beyond, those are goals, not mandates, and carmakers will continue to respond to marketplace demand.

If enough people want gas-powered cars in 2030 – just six short years away – carmakers will continue to make them.

Make no mistake, electric vehicles, with their superior performance and rapid development, will continue to gain market share, but Ford, GM, Stellantis, BMW and the Japanese carmakers producing only electric vehicles a decade from now seems unlikely and financially unrealistic, let alone sinking possible billions into robotic battery swap technology and standards.

It could happen, but as long as the price of liquid fuels continues to be tolerable, the changeover to EVs will ramp slowly rather than at revolutionary speeds.

Additionally, electric vehicle owners in the U.S. and EU already have a robust electrical infrastructure in place at home that makes vehicle charging as simple as plugging in a toaster, with an option to speed things up by installing a relatively affordable Level 2 charger.

Would battery swapping have a positive ROI in the U.S. that eventually makes it a profitable after a fairly large initial investment? At this time, it seems unlikely.

Again, China and Asia’s heavy prevalence of scooters makes such systems seem workable, and the Chinese government can mandate or just work with carmakers on battery specifications to support the swapping tech.

In the U.S. and to a lesser degree in the EU, scooters and motorcycles are still used mainly as pleasure craft, and are sold in vanishingly small numbers relative to Asia. Ko said that for now, the U.S. market is not a primary target for iONEX expansion due to those and other factors.

Additionally, no mass-market full-size electric motorcycles can currently utilize a swap system since the power packs are far too heavy for a single person to move.

Most likely, an automated system would have to be devised to enable a swapping strategy for motorcycles, but the problem of standardization again makes such a plan unlikely, given the investment required around both the batteries and the swapping system, which would again most likely not be standardized, limiting its earning potential.

But with the smaller battery requirements of a scooter, it’s a good fit, as KYMCO and Gogoro have shown.

One place where a battery swap system might have a chance in the U.S. is with electric bicycle (e-bikes), but again, some form of standardization within the industry would be needed, and that will require cooperation among rivals within the e-bike space, which is certainly possible, at least much more so than with cars.

But it would require a large change in how Americans view “recharging” or use ebikes, which are admittedly gaining favor in the last-mile delivery and commuting spaces. It’s a space worth watching closely.

Welcome to the swap-n-sip

Time will tell which EV “recharging” scheme wins out, but it would seem at some point market forces could coalesce around swappable batteries somewhere and drive them to a usable standard, perhaps with several battery size options.

Bottom line: It’s tricky when it comes to batteries, charging, swapping and standards, since the tech can quickly change. However, a battery swap system would be very convenient for EV drivers, who would pay for such a convenience, opening the door to monetizing such a service.

No one wants to wait hours – or even 15 minutes – for a vehicle to refuel. For scooterists and Nio EV drivers in China, a battery swap happens in less time than it takes to fill up with liquid fuel, just as Tesla demonstrated over a decade ago.

For them, the battery swap future has arrived. Will other companies duplicate the technology, or contract with vendors who can provide it?

The future is wide open.

No system is perfect and mistakes have taken place.

But on balance, the Chinese, Taiwan’s KYMCO and rival Gogoro have demonstrated that such a system is workable, especially for EVs that see a lot of road miles (or kilometers) such as scooters, small taxis, delivery vehicles of all types and the nascent crop of self-driving robotic vehicles – even full-size cars.

Elsewhere in the world, multiple technologies including hydrogen vehicles, plug-in hybrids, and competition make such standardization unlikely, and if a battery materials breakthrough takes place that gives EVs greatly expanded range with quick-charging capability, it could be a moot point in the end.

Stay tuned.

This article was first published on forbes.com and all figures are in USD.