A rare look inside the French family business defying the luxury giants – and the momentum pushing Longchamp into its strongest years yet.

Ask Jean Cassegrain if the family has ever considered selling Longchamp and he doesn’t hesitate. “No.” In a luxury market built on consolidation and scale, the 77-year-old French house remains one of the last large brands still fully owned and run by the same family that founded it.

Inside the company today are six Cassegrains – three from Jean’s generation and three from the next – working across markets, events and transformation. So when the question of handing control to someone else comes up, the head of the family responds bluntly and without blinking.

That continuity sits behind a rare streak of momentum. Longchamp posted back-to-back growth years: more than 40 per cent in 2023, followed by another 20 per cent in 2024, the strongest result in its history. The brand is now spread across more than 400 boutiques, supported by 4,245 employees and five French workshops that still handle the bulk of the leather goods work.

So, what are the conversations like over the family dinner table?

Far calmer than the question suggests.

Cassegrain, who is in Sydney for the first time since 2018 to visit Longchamp’s Australian team, says the three younger family members – his two sons and his niece – have slotted in seamlessly, and major decisions land with surprising ease. “It’s pretty consensual,” he says.

The company still behaves like a family operation even as the numbers look more like a mid-sized luxury group. Longchamp added roughly 800 jobs in the last two years. Asia-Pacific now accounts for 33.6 per cent of global revenue, and when you include travel retail, customers from the region drive about half of worldwide sales.

This year, the brand also opened a logistics hub in Hong Kong so Asian-made products can flow directly into Asian markets without being routed back through Europe. It cuts time, emissions and cost. Cassegrain says he believes it will reshape how Longchamp operates across the region.

“Maybe in a few years we’ll look back and see it as a milestone,” he says.

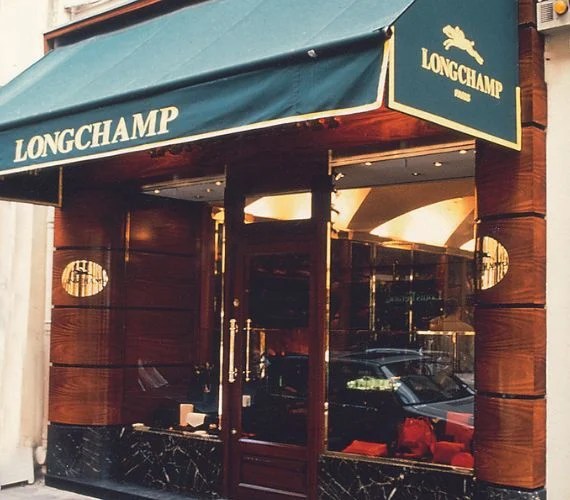

Retail has already hit that point. A decade ago, Longchamp looked like every other handbag brand fighting for attention in crowded malls. Now the stores have been stripped back, rethought and rebuilt. Less product. More space.

“The world doesn’t need more bags… the world needs shopping experiences that are new and exciting and fun and interesting.”

Jean Cassegrain, Longchamp CEO

That approach produced two of the brand’s most distinctive projects: the renovated Spring Street flagship in New York and Shanghai’s Maison de Famille, a 1920s house turned into a Longchamp-branded living space with a library and games room.

Online now accounts for 10–20 per cent of global sales depending on the market, yet the physical stores haven’t lost relevance, Cassegrain says.

In Australia, that mix shows up in the customer base, he says. Longchamp doesn’t skew to one demographic. Teenagers hunt for their first Le Pliage. Long-time buyers still carry pieces purchased decades ago. And the brand is one of the few you’ll spot in every cabin of a plane.

Growth, though, isn’t optional. Cassegrain is clear about that. Customers expect fast delivery, large-scale digital capability, multi-language sites, and stores that feel distinct. He is adamant that competing in that world requires scale, but not the kind of unchecked expansion that “dilutes the brand”.