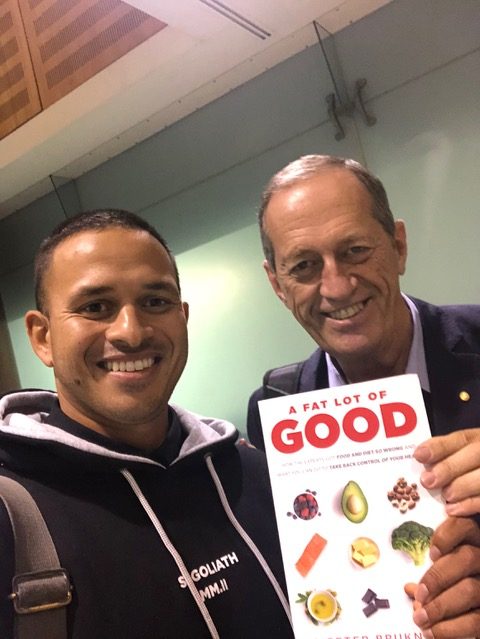

When young batsman, Usman Khawaja, came to sports doctoring legend Peter Brukner asking for weight-loss advice, neither man could foresee that it would change the way the doctor viewed health and lead to him forking out millions of his own money to launch a new approach to reversing diabetes.

The cricketer had come to the Australian team doctor hoping to lose a few kilos while they were on tour in India in 2013. Brukner, perhaps Australia’s most renowned sports medico, had recently lost 13 kilos, so he told Khawaja about the then somewhat controversial method that had worked for him – cutting carbohydrates and embracing fat.

“India’s not the easiest place to go low carb,” recalls Brukner. “But the good thing about sportsmen is they’re pretty disciplined.” A few weeks later, Khawaja reported back to the doctor that he’d forgotten to have his fortnightly injection for a severely arthritic knee that was endangering his career.

Usually, the pain would remind the batsman the shot was due. “I haven’t had any pain, so I didn’t get that reminder,” Brukner recalls Khawaja telling him. Khawaja – who’d lost his spot in the starting XI partly because of the knee problem – wanted to know if he still needed the injection. “No, no. Let’s just see what happens.”

What would happen was that Brukner would be forced to rethink everything he thought he knew about health and medicine. “Usman was able to throw away his $15,000 dollar-a-year drug. He was back in full training and within a year he was in the top ten batsmen in the world. That just blew me away. I’d never heard of that. That really opened my eyes to a lot of things and the fact that inflammation is the key to so much disease – from heart disease to depression.”

Khawaja wasn’t the only one to benefit. Batsman Dave Warner and all-rounder Shane Watson – whose early promise had been undercut by constant injury and weight battles – had also thrived after Brukner put them on the diet. Brukner watched with more than a little interest as Watson went on to achieve his greatest success in the long twilight of his career.

Brukner had done just about all there was to do in sports medicine. He’d written the international textbook. He’d founded Australia’s largest sports medicine clinic and then the Australasian College of Sports and Exercise Physicians. He’d been team doctor at numerous Summer and Winter Olympics, football and cricket world cups, for Essendon and Collingwood AFL teams, and, to top it off, he was running a family property business, The Brukner Group, which owns more than a dozen shopping centres across Australia and would be on the verge of troubling the scorers in the various published rich lists if it wasn’t so private.

He could have retired long ago, wealthy and fulfilled. At the age of 70, however, he is working harder than ever on a business venture attempting to disrupt the way we treat a disease implicated in the death of about 17,000 Australians each year, one in every ten deaths, and costing the health system $3 billion a year, according to the Australian Institute of Health and Welfare.

“He’s trying to create another legacy,” says his business partner and sports medicine disciple, Dr Paul Mason. “This is what he’d rather be remembered for.”

Together with dietitian Nicole Moore they launched an app in 2021, Defeat Diabetes, that directly contradicts the current standard of care for diabetes control. And they’re claiming extraordinary results with remission rates of more than 50% in an early, non-peer-reviewed study. This, for a disease which until recently sufferers were told was irreversible.

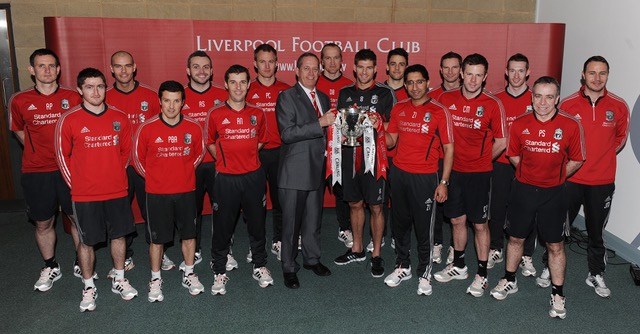

For Brukner, the journey goes back to 2012 when he was team doctor for Liverpool FC in the UK. If you’d asked him then, he would have told you he was healthy. He’d always followed the dietary guidelines, but despite all those healthy wholegrains, salads and low-fat everything, he’d put on half a kilo a year for three decades.

“I was borderline obese. My BMI (body mass index) was 30. I had a fatty liver, and, like a typical doctor, I ignored it … I now know that a fatty liver is a prediabetic state due to too much sugar, but I didn’t know that at the time. I have no doubt I would have been a full diabetic in a short period of time.” His father had been diagnosed with Type 2 diabetes around the same age. “I saw what happened to him. He developed a range of complications. It’s a major risk factor for a whole bunch of different conditions. It’s the main cause of blindness, of kidney failure, of amputations. It’s closely related to Alzheimer’s, heart disease and so on. It’s a silent killer.”

Around the same time, a colleague and friend, Tim Noakes, went public with his story of becoming diabetic despite running marathons and being one of the world’s pre-eminent sports medicine researchers. The South African professor experimented on himself by upping the fat and cutting carbohydrates.

“I remember hearing about Tim and thinking he’d lost the plot,” recalls Brukner. “We couldn’t possibly have had the whole of western society be wrong about fat and carbohydrates for the last 40 years. But Tim’s a super smart guy and he’s been right a couple of other times on theories of sport science, so I looked into it.

“I started reading every paper I could get my hands on, books … it blew me away. The more I read the more I thought, ‘Jeezus! this is incredible. I’m a scientist. I need to do research.’ I knew research with N=1 (a sample size of one) is a waste of time …. except when the one is you.”

He learned that low carb diets were being used to treat a huge range of problems from the neurological to cancer, intestinal disorders, and respiratory compromise. He got his bloods done and he weighed himself. 93kg. He’ll never forget that number. He stopped eating anything with sugar or carbohydrates. He started cooking food like his grandparents ate. More meat, fish, eggs, full-fat dairy and above-ground vegies.

“I ate like that strictly for three months. The first thing that happened was that I stopped being hungry. So instead of having my cereal at 8am and being starving at 10.30, I’d have bacon and eggs and I wouldn’t want to eat again all day. I went from three meals and three snacks a day to two meals. I started to lose weight, I started to have more energy. I didn’t feel sleepy during the day. My concentration was better. I stopped snoring.” He lost 13kg in 13 weeks. He felt guilty. Wasn’t weight loss supposed to be hard? His new blood results came back, and all the numbers were heading in the right direction. And the fatty liver he’d carried for a decade was resolved. The biggest complication, he says, was that he needed a new wardrobe.

He became an advocate for the way of eating, and even while Noakes and an Australian colleague, Dr Gary Fettke had to fight legal battles with medical bodies to be allowed to continue to tell patients to cut carbohydrates, Brukner was at a point in his career where he could welcome such a challenge. “If they want to come after me, I’m happy to debate that point. Medicine has got to be evidence based, and people can’t ignore the evidence.”

And as that evidence mounted about the effectiveness of cutting carbohydrates – irrespective of whether the patient lost weight – in reducing diabetes, Brukner kept waiting for a change in the official advice.

“But the diet promoted by all the dieticians and diabetes people was the exact opposite. It was a high-carb diet. They were so obsessed about fat. They thought, there’s a big association between heart disease and type 2 diabetes, so we’ve got to avoid fat. As a result, they’ve been advocating a high-carb diet for a disease of carbohydrate intolerance. It’s absolute madness. You’re sitting back screaming, ‘Someone do something about this!’”

“I could have done nothing, but you feel a little bit obliged to spread the word.”

Peter Brukner

Eventually he realised it was going to have to be him.

The UK and US both have long-running, well-studied apps using a low-carb approach to diabetes. In the US, Virta Health claims extraordinary result after five years. In the UK, an app-based programme claimed 36% remission of diabetes without any drugs and a 40% reduction in drug use for those using drugs. Of the 10 reviews of randomised controlled trials in the scientific literature, all found that low-carb diets were more effective in reducing diabetes than low-fat diets.

Based on those approaches, he invested “a seven-figure sum” of his own money towards developing Defeat Diabetes, a $99-a-year subscription app claiming huge success in its first year.

“We’ve formed a company, so it’s a commercial business, but the aim isn’t to make profit,” says Brukner. “We did our own survey of our initial cohort and the results were incredibly positive. We had more than 50% of people in the programme put their diabetes into remission – 52%. The average weight loss was 6kg in three months, people reduced their medications, and quality of life improved – very similar results to the UK and US. Everyone improved.

“The teaching has always been that you can’t put type 2 diabetes into remission; that it’s a chronic, progressive disease. You’re on medication for life and you’ve just got to avoid some of the complications. It’s what I was taught at medical school, and I think they’re still taught that. And if they eat a high-carbohydrate diet it remains absolutely true. They will stay diabetic for life.”

Dietitians Australia president Tara Diversi says it is a “misconception” that dietitians are opposed to low carbohydrate diets. “Dietitians are evidence-based, so we support anything that has good evidence behind it,” she says.

This might come as a surprise to dietitian Jen Elliott who, after 35 years of practice, was expelled by Dietitians Australia in 2015 and lost her job for advocating such a way of eating. Or orthopaedic surgeon Garry Fettke who was sick of amputating diabetic toes and was taken to the medical board at the behest of Diversi’s predecessors for advocating his patients cut sugar.

Crucially, Dietitians Australia ceased taking corporate sponsorships in 2019, cutting ties with its major “partners” who included Nestle, Coca Cola and Kellogs.

Diversi says Dietitians Australia does not have policies on what diet works for what illnesses, but follows the advice of the specialist groups like Diabetes Australia, which recently changed a key part of its approach, in 2021 recognising for the first time that type 2 diabetes could be put into remission – something low-carb advocates say they have been observing for decades.

For his part, Khawaja, a decade after fixing his knee, aged 36, continues to be one of the world’s pre-eminent batsmen and in January was named the Shane Warne Men’s Test Player of the Year, averaging 78.46 runs during the voting period and continuing his career best form in India earlier this year.

“The older I get I’m very mindful of how I eat and how I train,” he told the Unplayable podcast. “I love carbohydrates. I love bread, rice and pasta, but for me it doesn’t fit right. I don’t get enough out of it. I avoid those and eat fatty foods. Meat, eggs, avocadoes … It sucks at times but it’s worth it. You give yourself the best chance to go out there and bat for 550 minutes whatever I did the last game then go out there and field and bat again and field again.”

Brukner continues to eschew easy retirement and remains chair of the Sugar By Half not-for-profit. He has paid for a PhD student to study the effects of a low-carbohydrate diet on arthritis.

“I could have done nothing, but you feel a little bit obliged to spread the word.”