As a teenager, Miranda Wang took a high-school science fair project to the TED stage. Now she is leading Novoloop, a company betting that upcycling polyethylene into new polyurethane products can compete commercially – with Rolex backing her next phase of growth.

Miranda Wang was 16 when she first came face to face with the scale of the plastic problem. On a school trip to Vancouver’s South Waste Transfer Station, she stood over a pit of garbage and realised how little recycling really worked.

“One of the opportunities that we had as youth was to visit the Vancouver South transfer station, which is where garbage is compacted, and is essentially a holding place, before it gets transported at a local landfill,” she said.

“And I was extremely surprised when I visited this facility in 10th grade to see how much plastic was ending up in this waste transfer station and going to the landfill, which this transfer station is only a tiny fraction of.”

That early visit to the transfer station left a mark. Watching mountains of plastic tumble into a pit made clear how little of it was ever recycled. For Wang, the scene was both humbling and confronting – a stark reminder of where the materials we use eventually end up.

That moment stuck. With her best friend Jeanny Yao, co-president of the school environment club, she began testing ideas. “The first idea was, can we find bacteria… that can eventually eat plastics?”

The project caught unexpected attention. “The fact that we were mostly high school students and working on an environmental problem and doing a practical, science project, associated with that, caught the attention of the TED conferences.”

The invitation took them to California.

After their TED Talk, messages started arriving from around the world. “People from Africa, India, places we’d never been, were asking what they could do about plastic waste,” Wang said. “We were blown away by the level of interest and impact.”

It changed the trajectory of her life. “This… was the moment that made us realise we can turn something that we see as a problem that we’re passionate about into an effort that we work on in our careers, in our lives. And it gave us the confidence to pursue that further.”

By 2015, still students, Wang and Yao had met their first investor. “He funded our company before we even graduated.”

Building Novoloop

“What we have built over the last decade is a company called Novoloop,” Wang said. “And the reason we chose to set it up as a for profit was because we fundamentally believe that a financially sustainable organisation is what is going to allow a new technology for circularity, for transforming the plastic supply chain.”

She focused on polyethylene, the cheap, strong plastic used in shopping bags and packaging. “The market price is around $1 a kilogram. It’s very cheap… it’s very hard for recycled plastics… to compete against virgin polyethylene.”

So they went another way. “What we do is we take the polyethylene, we invented a new way to chemically transform it and upgrade its performance into another type of material… If we turn it into a material that’s worth more and has higher durability, the material can be put into longer lasting applications, then the fundamental economics become much more practical and feasible.”

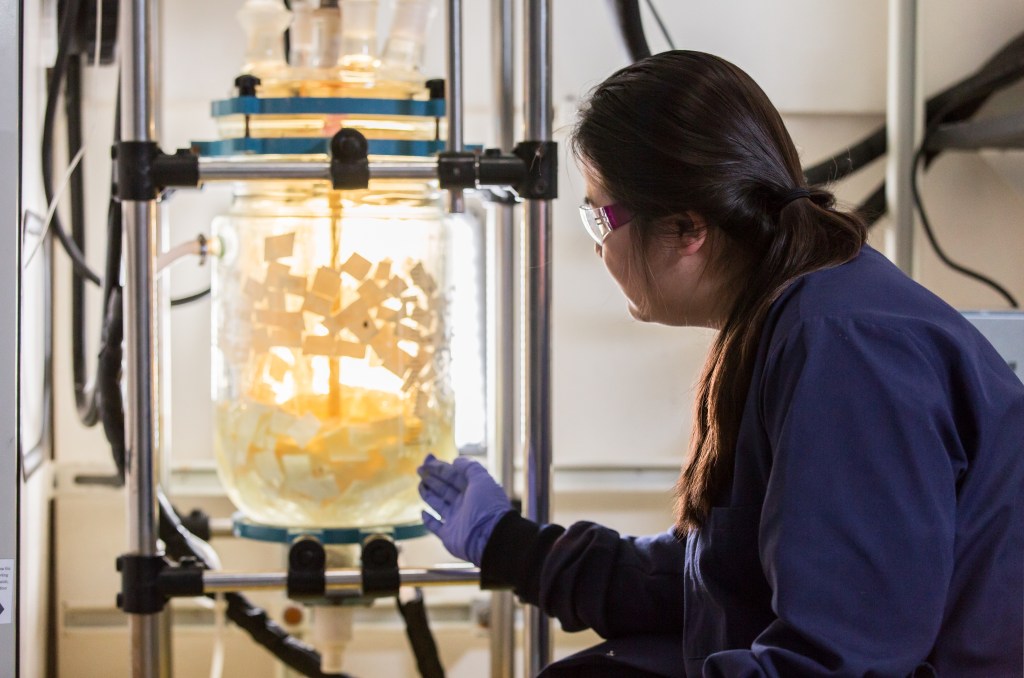

That process, called life-cycling, uses controlled oxidation to break down waste. “In most industrial chemistry, you have continuous processes. Things run 24-7, which means that there’s constantly something reacting.” The output: polyurethane for sneakers, mattresses, foams.

Scaling took years. “We took each of the steps, but we did not, you know, cut corners here because this is a new technology. It’s the first of it’s kind.”

Help came from Washington – and from Rolex. In 2019, Wang was named a Laureate of the Rolex Awards, an accolade that came with funding and international visibility. For her, the award was a turning point, giving Novoloop early capital to refine its chemistry and the credibility to pursue partnerships beyond the lab.

“Eventually, with the help of a U.S. Department of Defence Grants from DARPA, we were able to buy a reactor that we were able to assemble in our own laboratories and make into a continuous operation,” she says

‘What they care about is the impact’

Through the Perpetual Planet Initiative, Rolex doubled down on its support in 2024 to help Wang set up the demo plant in India. It came at a point when Novoloop, needed proof it could work outside the lab. The company had already shown that a single reactor could run continuously, but building a small-scale factory in India required another leap. Support from the Perpetual Planet Initiative gave Wang the chance to demonstrate the system in a real industrial environment, and the credibility that comes with being linked to a broader network of scientists and entrepreneurs through Rolex.

The facility, built with a local partner, ran for 100 hours non-stop in 2024. For Wang, that was the turning point. “Nobody really cares about the technology… What they care about is the impact of it. Are the materials affordable? Do they perform well? Are they easy to purchase?”

She frames the scale of the problem plainly. “We are producing over 400 million tons per year of plastic waste… by 2050, this number is going to more than double to over 1 billion tons of plastic produced per year from fossil fuel resources.”

Novoloop’s target is to intercept that stream. By 2030, the company projects converting 175,000 tonnes of plastic waste a year and cutting 800,000 tonnes of CO₂.

The climb is relentless. “After a while, you just become very expecting that there will be more problems,” Wang said. “We have multiple problems, but we have to decide what are the problems we’re actually best equipped to solve.”

Her discipline is to choose battles. “Over time, as you solve enough problems, you recognise the patterns, you recognise what you’re actually able to do and not.”

Support has mattered. “One of the first, like, aha moments I had in relation to the Rolex Awards was seeing the many decades of history this program has had, the types of things achieved by this community of Laureates, and individuals, there’s nothing more humbling to be told, like, you belong here… as part of this community.”

From a landfill pit in Vancouver to a TED stage, from a lab reactor to a chemical plant in India, Wang has carried the same question: what if plastic didn’t end in landfills?

“In my opinion, this problem is completely a business problem, but you need the right technology to be developed based on the realities that a business needs to be built upon,” she said. “And that’s what we have been doing really well, which is the reason why we still exist.”

This article is part of Forbes Australia’s editorial partnership with Rolex through the Perpetual Planet Initiative, which supports scientists and explorers finding real-world solutions to Earth’s most pressing challenges.

Learn more at https://www.rolex.com/perpetual-initiatives/perpetual-planet

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.