Google Australia announced a $1 billion investment in Australian digital initiatives in 2021. Two years on, Forbes Australia is given exclusive access to the ‘Hearing Hub,’ a recipient of the funds allocated under the Digital Futures Initiative. The Hub – headquartered at Sydney’s Macquarie University – brings together non-profits, the research community, and powerhouses like ASX Cochlear Limited.

This article was featured in Issue 8 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

Dr Kelly Miles was 33 when she completed her PhD in Cognitive Hearing Science. She began a postdoctoral research position at the Macquarie University Hearing Hub soon after. The 36-year-old became a mum for the first time in 2019, and a week later, woke up in a Sydney ICU having suffered a stroke.

“I couldn’t talk, I couldn’t read. I couldn’t write,” Miles says. “I had a one-week-old newborn. And I’m just lying there thinking. Firstly, how can I communicate with my baby? And then, I can’t believe I have been researching hearing this whole time rather than communication.”

It was a week that redirected Miles’ life. While she still works at the Macquarie Hearing Hub, her research now focuses on understanding the physiological responses during communication challenges. She runs the Ecological Hearing Outcomes (ECHO) Lab housed within the Hearing Hub.

“Our lab is dedicated to understanding communication difficulty,” she says. “As soon as there’s noise, it’s hard for people to communicate – and not just people who are deaf or wearing devices, it’s also bilingual people and people with communication disabilities like ADHD and autism.”

The Hearing Hub brings together the National Acoustics Laboratory, Cochlear Limited, Hearing Australia, Next Sense, Macquarie University Hearing, and the Shepherd Center on one campus.

“We look at what signals people are giving off that can index communication difficulty,” says Miles. “So, how are people moving together? How are their autonomic nervous systems aligning? Because we start to sync up. What are their eyes doing? And then, from there, we can extrapolate. Here’s this metric of this person’s difficulty.”

This research aims to assess physiological responses to determine when a person finds hearing challenging. Hearing devices can then be built to adapt to multiple environments and scenarios. One of the challenges is that variables can be measured, and not every person responds to being unable to hear in the same way.

“I might be able to detect communication difficulty for one person, but maybe that’s different for another,” says Miles. “How can we help the hearing device better understand that the person is having difficulty?”

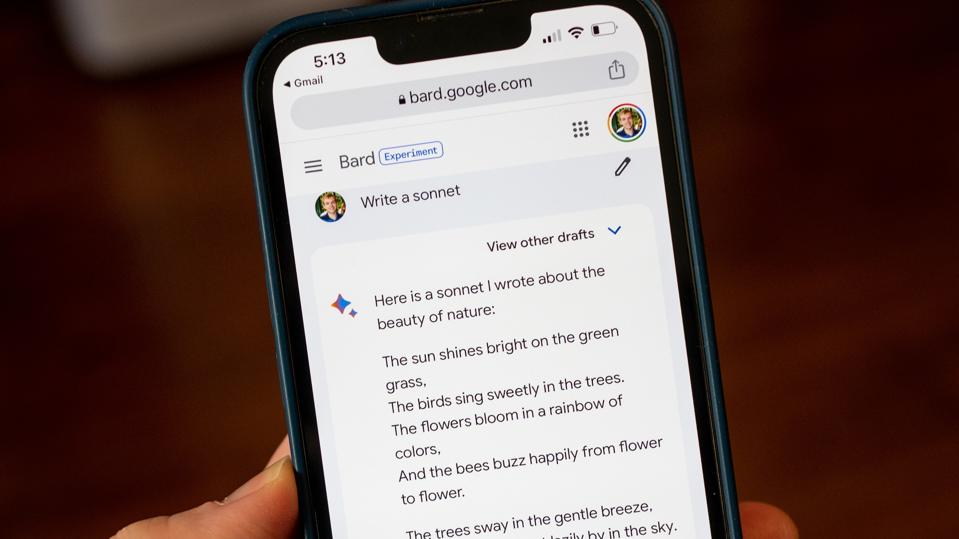

Analysing the data to personalise hearing aids to the specific and fluctuating needs of the user is something that the Hearing Hub’s new partner, Google Australia, is helping with. Miles says the technology in the proof-of-concept ECHO lab pushes the frontier of communication and hearing research, though it is the tip of the iceberg of what can be achieved with a partner like Google.

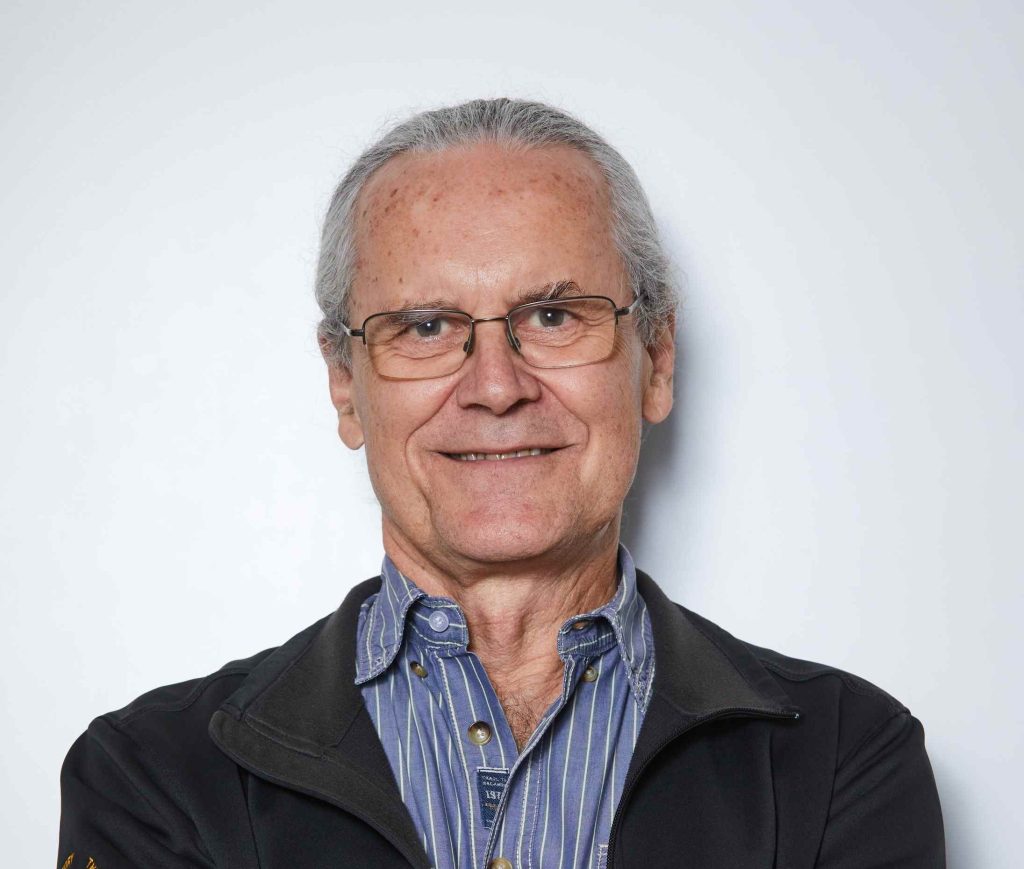

ECHO is not the only thing taking place at the Hearing Hub. Jorg Buchholz is an Associate Professor of Audiology in the Department of Linguistics and oversees the Hub’s anechoic chamber. He, too, says that the Google partnership has been invaluable.

“You have so much complex data coming in that you have to make sense of. Standard tools are not enough; new tools are needed, and that’s Google’s strength.”

Buchholz undertook a master’s and PhD in Electrical Engineering and Information Technology in Germany. He came to Australia because of its reputation as a world leader in hearing research.

“Simon Carlile was a mentor to me for many years, and now he’s a researcher at Google,” says Buchholz. “Google is contributing brain power and ideas. A project of this scope is an enormously expensive endeavour, so funding is also important. The engineers, the audio-visual processing, and the researchers analyse huge data sets.”

Buchholz says that kind of collaboration happens in the anechoic chamber found at the Hearing Hub and in the boardroom.

“It’s bringing people together around one table,” he says, which is no small feat given the intellectual property and varied interests of the Hearing Hub’s academic and commercial members.

“The different parties have different IP agreements. All of these things usually stop when you work with industry. The policy was always that it is public domain.”

Not a uniquely Australian problem, but a uniquely Australian solution

Australia holds a unique position in the global hearing ecosystem. Hearing researchers flock to Australia to be a part of the work pioneered here over 90 years. The Hearing Hub at Macquarie University in Sydney opened in 2013.

It was announced earlier this year that Google Australia is contributing resources and funds to the Hearing Hub as part of its Digital Futures Initiative. The collaboration aims to improve the function of hearing aids and other listening devices.

Australia’s National Acoustics Laboratory, the research division of Hearing Australia, says that those environments are particularly challenging for device users “due to the overlapping sounds, which are strenuous and overwhelming to process. The application of AI to categorise and prioritise certain sounds in such environments presents a chance to improve the lives of countless people facing these situations.”

The ‘cocktail party’ problem – not being able to differentiate between noise in a crowded room – is known, and something Google Australia is collaborating on with the Hearing Hub.

Dr Simon Carlile, the project lead at Google Research Australia, understands the problem all too well. Not only has the Australian neuroscientist dedicated his career to understanding difficulties brought about by hearing loss, but a personal experience with his father, who wore hearing aids in the 90s, changed the direction of his research toward communication.

“Dad turned up without hearing aids, and I said, ‘Dad, you’re not wearing hearing aids. Why not?’ And he said, ‘They don’t help. I can’t separate anything. It’s all loud and messed up’” says Carlile.

“It occurred to me that I have to do something about this. I had been doing stuff in virtual reality for other perceptual areas in hearing. Over the next 12-18 months, we slowly shifted into more clinically orientated things, particularly trying to solve the cocktail party problem.”

Carlile became a Vice President of Research at Starkey Hearing Technologies and the technology lead and director at Google’s parent company Alphabet’s X Moonshot Factory in the US. He returned to Sydney to get involved with the Hearing Hub and is now the lead conduit between it and Google. He chairs the research committee for the Hearing Hub and helps decide how the $1 billion Digital Futures Initiative will be used.

“We have been able to work on a consensus basis to date, and we haven’t had to vote on anything. There’s enormous goodwill there because of our common purpose. Everyone on that committee has spent most of their professional life trying to solve these sorts of problems.”

In just nine months since the partnership was initiated, the team has finished building and validating ‘baseline’ AI models to determine whether the model works as effectively as current state-of-the-art hearing aids and cochlear implants.

“This model can be used as a benchmark. The next stage will be exploring ways the models can

be tuned to more effectively meet the needs of the individual listener,” Google Australia says.

Nextsense, formerly the Australian Institute for Deaf and Blind Children, announced last year it is building a new $75 million building on the Macquarie Hearing Hub campus. It is partly funded through a $12.5 million federal government grant.

Deloitte Access Economics and the Hearing Care Industry of Australia (HCIA) conducted a report on the economic impact of hearing loss in 2017. That research revealed that the overall cost of hearing loss in Australia is $33 billion.

Australia is one of the only countries worldwide that takes a holistic, preventative approach to hearing loss. Figures from 2008-2009 reveal that the federal government invested $309 million into hearing assessment, hearing aid vouchers, and maintenance in one year alone. Last year, the federal government announced a $7.5 million increase in investment in hearing health.

David McAlpine, Distinguished Professor of Hearing and Academic Director of Macquarie University hearing says, “Hearing loss is the single biggest sensory deficit. One of the things Australia’s done well is dominate the basic research understanding of the inner ear and the brain. There is nothing like [the Hearing Hub] globally, not in cancer, immunology, or any other discipline. It is uniquely Australian.”

The next frontier of hearing research is less focused on fixing the inability to hear sounds – which Australian company Cochlear solved more than 40 years ago – and related to optimising communication for the billions of people worldwide who have partial hearing loss.

“The next step is communication,” says McAlpine. “Understanding how the brain responds to hearing loss or communication issues, how it develops in a language context, and how it copes with listening to noise.”

“Industry captains, government agencies, university leaders, not-for-profit partners, and partners we bring in are making funding decisions and developing policy. That all comes to fruition in one place,” says McAlpine.

While it is the sensory disability that impacts the most people, there are fewer research dollars spent on hearing than on other sensory disabilities, McAlpine says. “If you are going to be born deaf, the best country to do it in is Australia,”

Australia’s expertise in hearing loss extends back to 1947. The federal government set up an organisation called Hearing Australia during the rubella epidemic. Its mandate was to screen children who had rubella for hearing issues and provide support to WWII veterans who had returned from the frontlines with hearing loss.

In 75 years, it has expanded to screen all newborns for hearing loss and provide support for children with hearing loss until the age of 26. It also provides resources to pensioners, Indigenous adults over the age of 50, and veterans.

The international hearing community looks to Australia partly because of its pioneering work developing the cochlear implant. In the early 1960s, Professor Graeme Clark began working as an Ear Nose Throat surgeon at the Royal Victorian Eye and Ear Hospital. Clark was not satisfied with the solutions to treat deafness in his patients, and in the 70s, experimented on animals to see if they could tolerate hearing implants.

In 1978, it was implanted in an adult who had been deaf for two years. While the patient’s hearing was not perfectly restored, the multi-channel cochlear implant effectively produced hearing sounds and sensations.

Cochlear Limited was founded in 1981 and manufactured the first multi-channel implant system that received clearance from the US FDA. One year later, the first Cochlear device was implanted. Today, more than 600,000 Cochlear Limited devices have been implanted in more than 400,000 patients. Having Cochlear’s headquarters on the Macquarie University campus gives the Hearing Hub an advantage enabling collaboration with other entities researching in the hearing space.

The National Acoustics Lab published research this year studying the hearing and wellness benefits of replacing and upgrading old Cochlear implants – also research on mask wearers. Studies have found 80% of respondents had difficulty understanding others who wore masks.

It found that an inability to lip-read masked faces and the material barrier of a mask softening audible sounds compounded hearing challenges.

The Godfather, the Internet, and accesibility

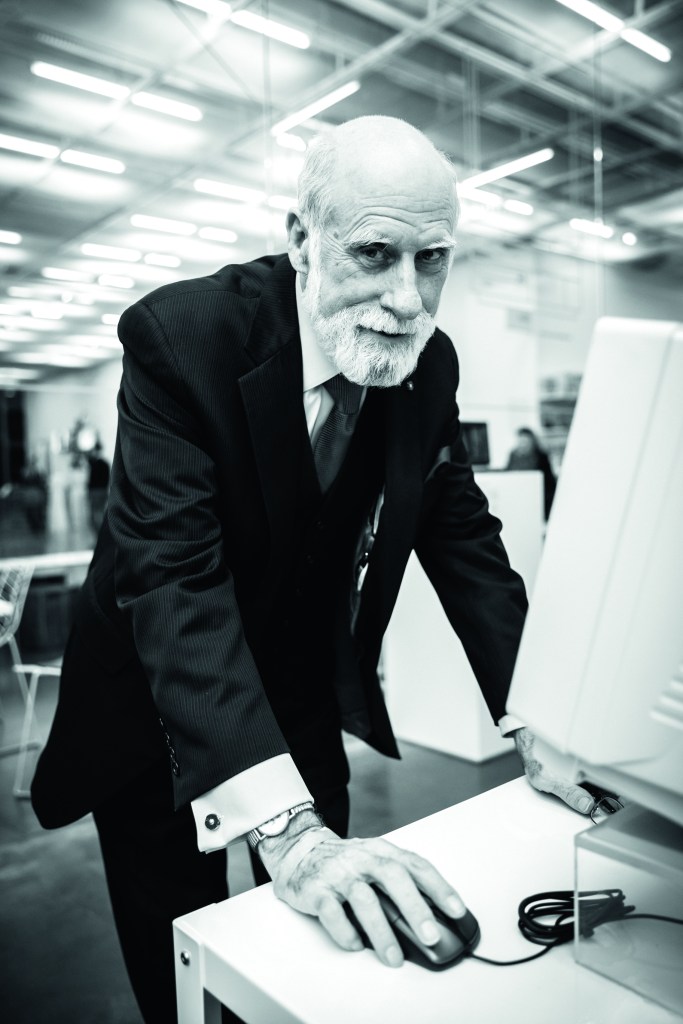

Vint Cerf, known as the Father of the Internet, and Google’s Chief Internet Evangelist has a personal connection to hearing loss.

In 1996, when tech behemoth Google was created, Vint Cerf, who developed the infrastructure that gave rise to the internet, spoke to his wife of three decades on the telephone for the first time.

“She was deaf for 50 years,” Cerf says about his wife Sigrid.

“She had a cochlear implant in 1996. They activated the speech processor, and 20 minutes later, she called me on the phone. We had been married for 30 years and could never use the phone together.”

Sigrid Cerf is one of 1.5 billion people worldwide with hearing loss. That one-in-five statistic is predicted to worsen as the population ages. In Australia, the figures are only marginally better. One in seven suffer from hearing impairments, and that number is expected to climb from 3.6 million people to 7.8 million in 40 years.

“Big rooms full of people all talking at the same time, that’s also really hard for me,” Cerf says. “I will often either opt out or, if possible, find a quieter room.”

The Australian-invented cochlear implant transformed Cerf’s and his wife’s lives. The Cerfs rely on digital innovation to assist with their hearing challenges.

Diagnosed with diminished hearing as a child, Vint Cerf has worn hearing aids since he was 13. “I couldn’t function without the benefit of these technologies,” he says.

Cerf attended Stanford University and went to work at IBM as a systems engineer. Cerf then moved to Los Angeles, where he met Bob Kahn, his co-inventor of the protocols underpinning the World Wide Web.

Empowering people to communicate efficiently and effectively has been a throughline of Cerf’s storied career. He sees creating the internet with Kahn as similar to his work in accessibility. In both scenarios, the focus is enabling people of all shapes and abilities to connect seamlessly – whether in person or from the other side of the world. “I would like our programmers to have an intuitive understanding of what it means to be accessible,” he says. “You need to understand how a disabled user uses assistive technology.”