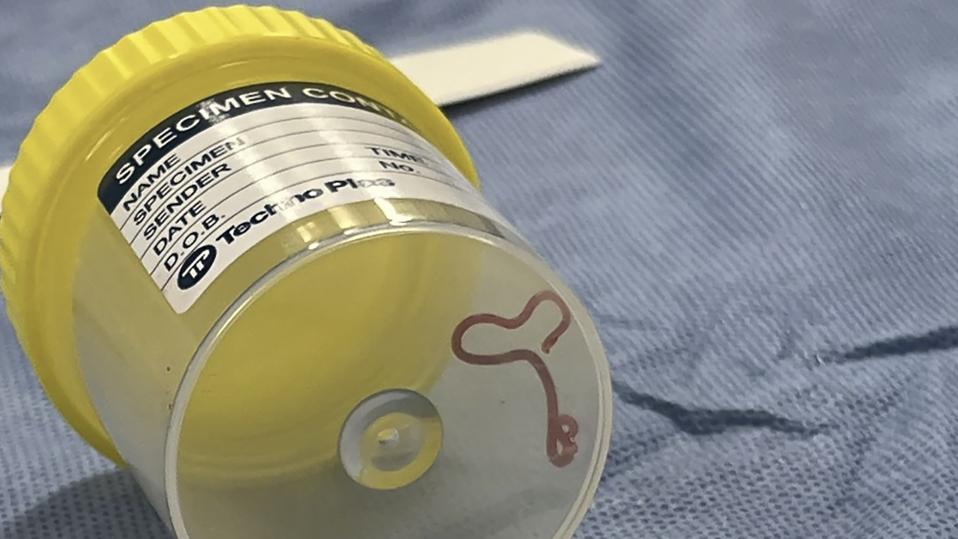

Neurosurgeons in Australia this week reported pulling a live, three-inch worm from a woman’s brain, a shocking, world-first discovery that adds another threat to the catalog of dangerous worms and parasites that already target billions of people around the world.

A 3-inch wriggling worm was pulled from a woman’s brain.

Canberra Health Services

Key Takeaways

- Experts said the woman likely became an “accidental host” for the parasitic worm after inadvertently consuming parasite eggs from grass contaminated with python faeces she had collected near her home.

- The exposure to python faeces needed for infection means future cases are possible but are likely to remain rare and the scientists stressed the worm does not have the same pandemic potential as other pathogens that have crossed from animals into humans like the agents behind Ebola, Covid-19 or SARS, as it does not transmit from person to person.

- However, there are many parasites that do infect people with much greater frequency—some evolved with humans as a crucial part of their life cycle—and parasitic infections are responsible for causing huge death tolls, significant ill health and disability and perpetuating cycles of poverty and inequality in areas affected.

- According to the latest Global Burden of Disease Study, a comprehensive look at the causes of death and disability worldwide, some 2.35 billion people were living with parasitic infections in 2019, with an estimated 678,000 deaths and more than 58 million years of healthy life lost, a metric researchers use to quantify the impact of outcomes other than death.

- Malaria, a serious disease caused by a group of parasites spread by the bites of mosquitoes, was the biggest threat by far, killing more than 643,000 people and causing more than 231 new million infections and the loss of an estimated 46 million years of healthy life.

- More than 900 million people had infections with intestinal nematodes, worms like hookworm that feed on their hosts and impair growth and development, with 140 million living with schistosomiasis, parasitic worms spread by freshwater snails that can cause organ damage, 72 million with lymphatic filariasis, a painful and disfiguring parasitic disease also known as elephantiasis, and 19 million with onchocerciasis, or river blindness, which is one of the most common infectious causes of blindness in the world and spread by the bites of blackflies.

Key Background

There are three main types of parasites that can cause disease in humans: protozoa, helminths and ectoparasites. Protozoa are single-celled organisms like the malaria parasite or Giardia, which causes the diarrheal disease giardiasis, that are often picked up in the environment (such as eating contaminated food) or via a vector like mosquitoes.

Helminths, a group of multicellular worms that can be visible to the naked eye, infect a huge portion of the world’s population and large numbers of animals as well. Ectoparasites are a broad category of external parasites that feed on humans like fleas, mosquitos, lice, ticks and mites.

They can transmit other types of parasites—like the ones that cause malaria, river blindness, Chagas and leishmaniasis—in addition to other viral and bacterial pathogens responsible for a wide array of major health issues including Zika, yellow fever, West Nile, Lyme, Japanese encephalitis, dengue, typhus and Yersinia pestis, the plague bacteria thought to be responsible for the Black Death.

Many parasitic infections are easily treatable with existing medicines and preventable through improved sanitation and interventions like mosquito nets or managing the environment, though prohibitive costs and the lack of global effort to tackle the diseases mean these are out of the reach of the people most affected.

The majority of the burden falls on the world’s poorest, a status in part due to the consequences of prevalent parasitic infections. More than half of the diseases featured on the World Health Organization’s neglected tropical diseases list—11 out of 20—are parasitic. Parasitic diseases are also a problem in wealthier parts of the world. In the U.S., the CDC lists several—including Chagas, cyclosporiasis, cysticercosis, toxocariasis, toxoplasmosis, and trichomoniasis—as public health priorities.

News Peg

Surgeons and researchers in Australia expressed their surprise when they found a living worm inside a 64-year-old woman’s brain, which they said could have been alive inside of her brain for up to two months. The discovery, described in a study published in the journal Emerging Infectious Diseases, came after the woman went to hospital with symptoms of coughing, fever and complaints of depression and forgetfulness, with an MRI scan revealing an abnormal lesion in one of the brain’s frontal lobes. Parasitologists identified the worm as Ophidascaris robertsi, which is common among the carpet pythons found across Australia. The researchers said the patient is still being monitored by a team of infectious disease and brain specialists.

What To Watch For

Sanjaya Senanayake, an associate professor of medicine at the Australian National University involved in the discovery, said the case is a warning about the risks of humans encroaching on animal habitats and the importance of monitoring for new infectious diseases. Around three quarters of the new infections found over the last 30 years have moved into humans from animals, he said. “This is an issue we see again and again, whether it’s Nipah virus that’s gone from wild bats to domestic pigs and then into people, whether it’s a coronavirus like Sars or Mers that has jumped from bats into possibly a secondary animal and then into humans,” he told the BBC. Senanayake stressed the parasite won’t cause a pandemic like Covid-19 but said it “is likely that other cases will be recognised in coming years in other countries.” Senanayake said.

What We Don’t Know

Given the nature of parasitic infections, health experts and agencies say estimates of their prevalence and the health burden imposed by parasites are likely to be significant underestimates.

Crucial Quote

Canberra Hospital’s director of clinical microbiology and associate professor at Australia National University Medical School Karina Kennedy said the take home message from the discovery is about food safety, especially when gardening or foraging in areas where there may be wildlife nearby. “People who garden or forage for food should wash their hands after gardening and touching foraged products,” Kennedy said. “Any food used for salads or cooking should also be thoroughly washed, and kitchen surfaces and cutting boards, wiped down and cleaned after use.”