David Carbon went from fixing washing machines in Melbourne to building Amazon’s global drone fleet. Now he’s eyeing Australian skies.

David Carbon, the Australian leading Amazon’s ambitious drone delivery program, wants to see its autonomous aircraft flying across his home country — preferably before he retires.

But when asked for a timeline on that, or perhaps his age, Carbon sidesteps like a drone dodging a Hills Hoist.

“Not immediately, but not in the too distant future … We’ve got no immediate plan in the next 12 months to bring it here,” he tells Forbes Australia, from his hometown of Melbourne which he is visiting from his Seattle base. “But I’d certainly like to think we’ll bring it here — with my accent.”

Carbon is vice president and general manager of Prime Air, Amazon’s drone delivery division. Under his leadership, the program has moved from proof-of-concept to commercial reality, with tens of thousands of autonomous deliveries completed in the U.S. since the launch of its latest drone model, the Mk30, in November 2024.

The Mk30 is capable of flying beyond visual line of sight, autonomously avoiding obstacles — and, crucially, navigating dense urban environments. But it still only delivers in two places – West Valley Phoenix metro area in Arizona and College Station, Texas.

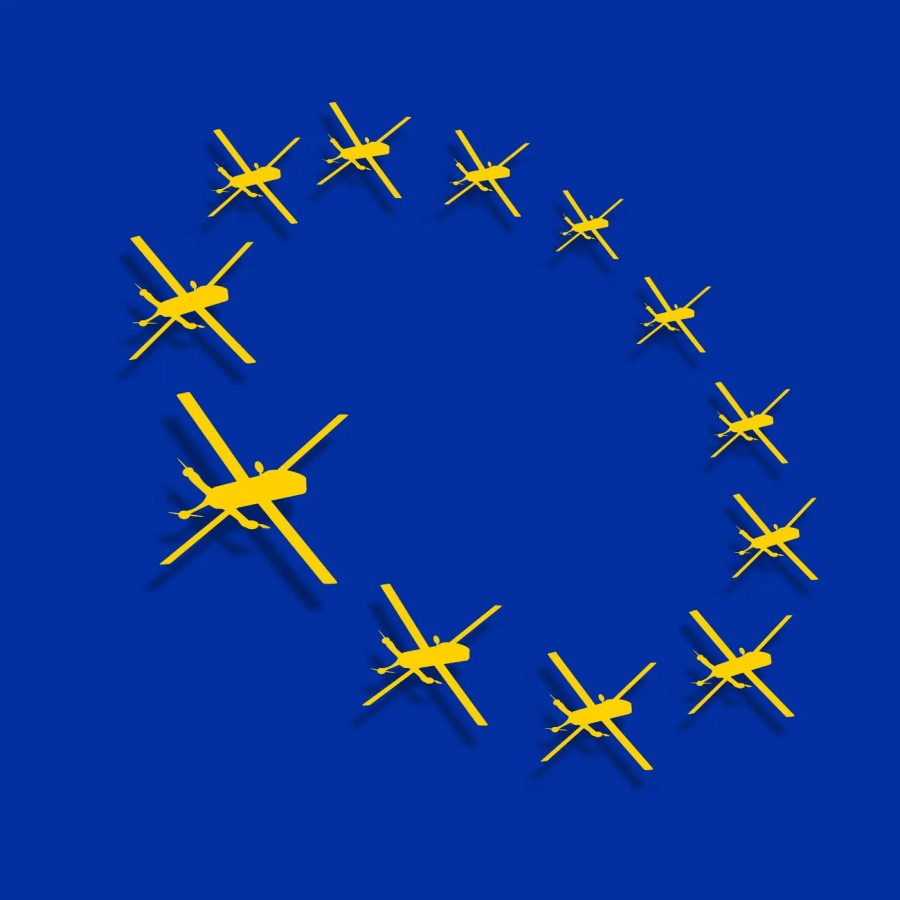

“We’ll scale to at least an additional six by the end of this year in the U.S., and then we’ll launch a site in Italy and in England — maybe by the end of this year, but definitely by February next year,” Carbon says.

While the U.S. and Europe are first in line, Carbon insists Prime Air was designed from day one to go global. “Speed is important everywhere,” he says. “As we build out the fulfillment network in Australia — and, you know, if I understand it correctly, Perth at the start of May got Prime same-day delivery, which is awesome — we’ll be ready.”

Amazon currently operates seven fulfillment centres and 12 delivery stations across Australia. But it’s yet to announce any drone delivery trials or regulatory agreements here — despite growing local activity in the space.

Swoop Aero, a Melbourne-based drone logistics start-up that gained global attention for its humanitarian delivery missions during COVID-19, was placed in administration late last year, after having received $26 million in backing from investors including the CSIRO’s Main Sequence Ventures.

Meanwhile, logistics giant Toll entered the drone space in 2023, buying Air Support Queensland, joining a wave of players looking to commercialise unmanned aerial operations in Australia.

At Prime Air, we’re Boeing… we’re Qantas… we’re the air traffic authority… and we’re Expedia. We sell the tickets. There’s no job on earth quite like it.

David Carbon, vice president of Amazon’s Prime Air

Still, Carbon draws a line between experimental flights and what he calls “scaled commercial delivery”.

“There’s a difference between doing it to scale and doing it because you can deliver a package,” he says. “People live in cities, not on farms, typically — that’s where our customers are, and that’s the drone we need.”

So how did Carbon – who grew up in Broadmeadow, in Melbourne’s battler north – end up in Seattle working for Amazon?

“What’s the old saying, it’s an overnight success that took 40 years or something.” His Maltese-born father worked for Qantas and had a side hustle fixing washing machines, which Carbon helped him with. An industrial relations graduate, he got work with Ford at Broadmeadow working in operations before a call from Boeing saw him working for them, first in Australia, then at Seattle HQ, eventually running both the 747 and 787 production programs.

He retired from Boeing in 2019, returned to Melbourne to care for his parents, and soon after got another call—this time from Amazon. In 2020, on the first day of COVID lockdowns in Seattle, he started his new job, tasked with turning Amazon’s experimental drone delivery project into a fully operational service. His brief was clear: figure out how to get packages to customers in under 30 minutes, but remain technology agnostic. “If we could deliver packages in 15 minutes with pigeons, we’d do it. We use a drone because it’s the best way to deliver to somebody quickly without interruption.”

The challenge wasn’t just technical—it was systemic. “The drone flies through the air, but regulators had never imagined autonomous vehicles in national airspace,” he explains. But his team did not adopt the start-up practice of moving fast and breaking things, like laws.

“We didn’t say the rules don’t apply to us,” he says. “We asked, which ones do, and how do we meet them?”

That meant, for example, obeying no-fly zones around airports, embedding perception systems that could detect and reroute around hazards—even if communications were jammed—and navigating requirements designed for human pilots, despite being semi-autonomous. They worked within the FAA’s 400-foot ceiling for low-altitude vehicles and engineered fail-safes that mirrored commercial aviation standards.

But the real engineering puzzle lay in the trade-offs. “The drone can’t be too heavy or noisy, but it still has to carry meaningful payloads,” Carbon says. Working backwards from the customer, they asked: where are people located? What do they order? And how fast do they expect it? The answer: most Prime customers live within 12 kilometres of a fulfilment or “sub-same-day” centre. Over 60% of what they order fits into a shoebox and weighs less than five pounds [2.3kg].

That set the design brief: build a drone that could hit those requirements and integrate into Amazon’s logistics system. “It’s not just a drone—it’s a complete ecosystem,” he says. “At Prime Air, we’re Boeing and Airbus. We’re Delta, Qantas and Virgin. We’re the air traffic authority. We manage airspace. And we’re Expedia. We sell the tickets. There’s no job on earth quite like it.”

How it works

When ordering on Amazon in a drone-eligible area—say, Phoenix—you’ll see Prime Air as a delivery option. Like choosing next-day or same-day, you’ll see “delivery in under 60 minutes” alongside your item. If you select it, a screen pops up asking where you’d like the drone to drop the package—front yard, backyard, a shared space in an apartment building. Once you confirm and pay, the drone heads out and delivers it, often within 30 to 52 minutes. You’ll get a notification when it’s dropped.

Wind, dogs and children can be confounders. “If the wind gusts hit 23 miles per hour [37km/h]—our max limit—or your dog runs underneath the landing area, or you’ve put up a new structure in the yard, the drone won’t deliver,” he says. “In those cases, the safest thing is not to deliver.”

The drone can fly in light rain and, eventually, Carbon says, in snow and ice. Amazon has worked closely with regulators like the FAA in the U.S., EASA in Europe, and the CAA in the UK. “Those platforms tend to set the tone globally,” he says. “I met with CASA [Australia’s Civil Aviation Safety Authority] last year, and they were great. Everyone works off treaties, and I’d expect it to be similar here.”

And so when exactly will he retire? “I’m old enough to know better than to answer that and young enough to be around a while yet.”