Biotech startup eGenesis developed a gene-edited kidney that was successfully transplanted into a living patient last week. Its CEO says the company is just getting started.

Surgeons perform the world’s first genetically modified pig kidney transplant into a living human at Massachusetts General Hospital.

MASSACHUSETTS GENERAL HOSPITAL

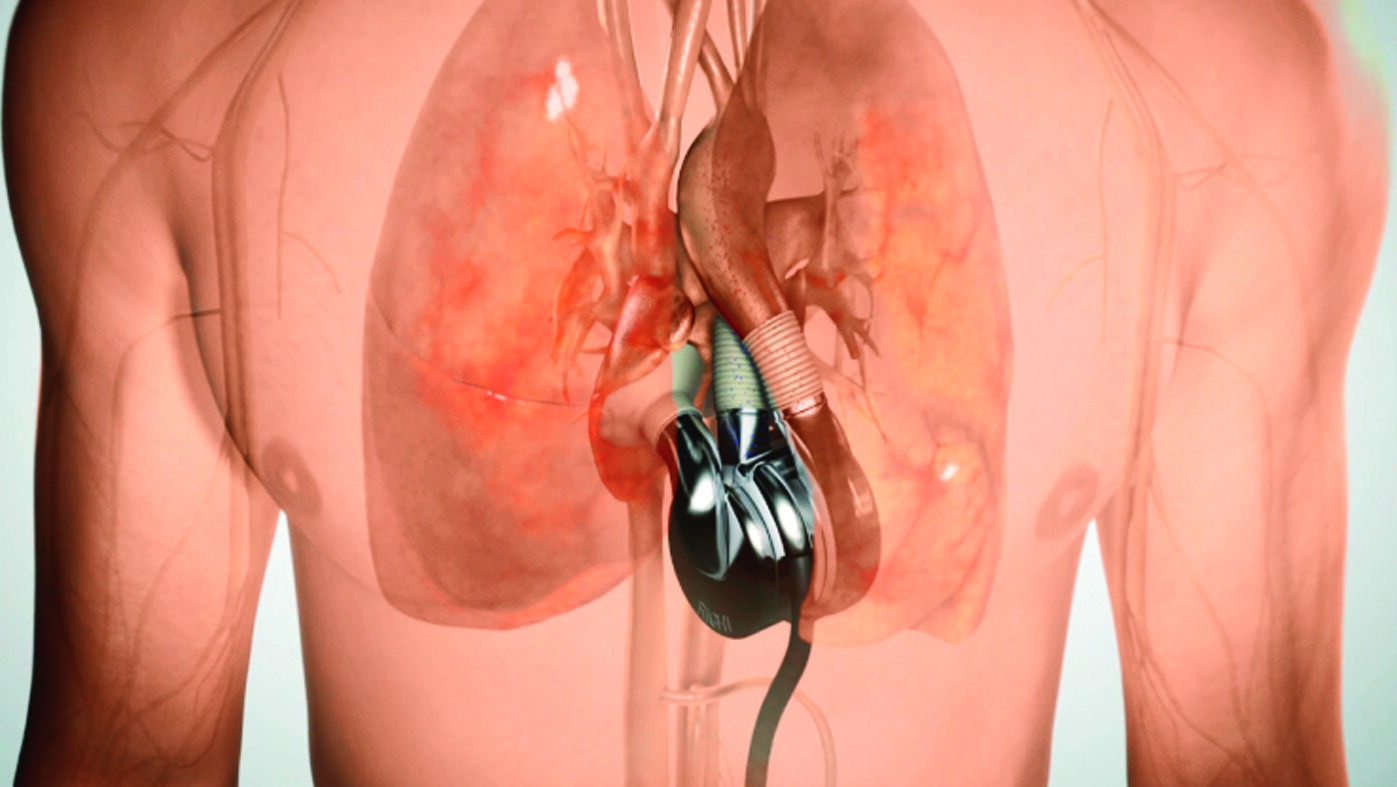

Last Thursday, surgeons at Massachusetts General Hospital announced that for the first time, a living human patient had received a kidney transplant from a pig. This scientific breakthrough represents hope for the dozens of people who die every day waiting on an organ transplant, the hospital’s transplant director Joren Masden said at a press conference following the announcement. “The dream of transplant researchers – the Holy Grail – has been to use pig organs to supplement human organs to solve the problem of organ shortage,” he said.

Of course, it wasn’t as simple as just going down to the farm. The kidney was developed by Massachusetts-based startup eGenesis, which has been working on gene-editing porcine organs so that they can be safely transplanted into humans for nearly a decade. But CEO Mike Curtis told Forbes that this week’s milestone is only the beginning. His company, which has raised $291 million in venture backing to date, aims to bring its gene-editing technology for kidney, liver and heart transplants into clinical trials in the next two years, making it a disruptive player in a market that Grand View Research estimates to be around $15 billion.

Related

“We’ve shown that we actually have something that can help patients,” he said. “To me it’s all about getting into this new era of science and the ability to help people that have very few treatment options.”

There are over 100,000 people in the United States currently on transplant waiting lists, but less than half of those will get a transplant in a given year due to the limited availability of donor organs. For decades, scientists have thought that animal organs might help some patients, even if they’re just a way to keep people alive long enough to receive a human organ. Pigs are an ideal candidate to provide donor organs because they grow up quickly and their organs have similar size and functionality compared to humans.

In this case, the patient was a 62 year-old man whose previously transplanted kidneys had failed, and the procedure was allowed to move forward under the Food and Drug Administration’s “Expanded Access” program, which allows patients with life threatening conditions to take advantage of experimental medicines or procedures. This operation followed several different experiments using pig kidneys with brain-dead donors, as well as two operations where living patients received transplanted, gene-edited pig hearts.

Jamil Azzi, a transplant surgeon at Brigham and Women’s Hospital who was not involved in Thursday’s surgery, praised the operation. “It’s a great breakthrough that was decades in the making,” he told Forbes. That said, he cautioned that a lot more data will be needed before this type of surgery becomes routine for human patients. A crucial question is how long a donated pig kidney will last in a human patient. “If it fails in two to three months, then we’re far behind,” he said. In 2023, two patients who received pig heart transplants, developed by United Therapeutics subsidiary Revivicor, died a few weeks after their operations, though it’s not yet completely clear why.

As scientists learn more about how pig organs work in humans, it may be possible to genetically engineer them to require fewer immunosuppressive drugs compared to a human organ—or none at all.

MASSACHUSETTS GENERAL HOSPITAL

One of the biggest challenges with an animal-human transplant is ensuring that the body of the person receiving the transplant doesn’t reject the animal organ outright. This is already a problem with human-donated kidneys, and skeptics have said that the number of differences between pigs and humans would make a transplant like this impossible. That’s where gene editing comes in. For last week’s operation, Curtis explained, it was necessary to genetically modify the donor pig’s kidney with seven different human genes, remove three pig genes and 59 additional pieces of DNA. These edits ensure that the kidney won’t be attacked by the patient’s own immune system to the point of rejection, though immunosuppressive drugs are required just as they are with human organs.

These edits were made to a single pig cell, which was then incorporated into an embryo and cloned. The cloned embryos were then implanted in a sow that gave birth to piglets with the genetic changes.

Having so many changes, Curtis explains, increases the risk of other parts of the animal’s genome being unintentionally altered — what’s known as “off-target” edits. But over the past few years, advances in genome sequencing have made it possible to detect if off-target edits occurred. In the case of this particular pig, the company was able to determine that such edits were minimal and wouldn’t have any effect on the outcome.

In a paper published in Nature last fall, the company showed cases where monkeys that had received pig kidney transplants survived for over a year — in one case over two years. Between that data and the successful kidney transplant this year, Curtis said eGenesis is progressing towards being able to formally file an application with the FDA to start a full-fledged clinical trial to implant more pig kidneys in humans as early as 2025. It’s not quite there yet though: Curtis said the agency still wants to see more primate data before giving the company a green light. Though more data is needed, Azzi added that what’s been demonstrated so far is a “good indicator” that the company is on the right track.

One thing the company will need to do in order to scale, Curtis said, is to get to the point where their pigs can be bred with ready-to-donate organs, rather than requiring cloning and implantation. George Church, an eGenesis cofounder and genetics researcher at Harvard Medical school, told Forbes that this might also provide opportunities for a single pig donor to provide multiple organs to patients.

“Ultimately, the vision is to produce organs in the pig that don’t require immunosuppression.”

Mike Curtis, CEO of eGenesis

Closer to fruition, Curtis said, is the company’s programs for editing pig livers and hearts for transplant into humans, which uses a similar process to kidneys. In January, the company announced a successful operation using a gene-edited pig liver with a brain-dead patient where the organ was connected to the body externally. This procedure could help patients with liver failure survive a crucial few days – long enough to receive a full transplant from a human donor.

Thanks to this success, Curtis said that his company intends to file an application with the FDA for its gene-edited livers and aims to begin clinical trials by the end of this year. Eventually, the company aims for its livers to be fully transplanted in living patients.

Permanent transplantation is the goal for eGenesis’s kidneys and livers. But when it comes to its heart program, he said eGenesis is mostly looking at pediatric patients, for whom a pig heart could serve as a viable bridge until they can receive a human organ. Currently, he said, over 50% of children who need a new heart die while waiting for a transplant. The company has currently seen baboons with gene-edited hearts survive over 200 days so far, and Curtis said he hopes that this could “lead to progression towards pediatric heart transplant, either later this year or early next year.”

In the long run, the company has even bigger ambitions. “Ultimately, the vision is to produce organs in the pig that don’t require immunosuppression,” said Curtis. That could mean that transplant patients wouldn’t have to go on a regimen of drugs that slow down the immune system in order to prevent rejection. While this keeps them alive, it also puts them at a higher risk for infections and cancer. “We know that’s going to require additional engineering, but we’re going to need the human data to help inform what the engineering looks like.”

Genetics researcher George Church, an eGenesis cofounder, added that in addition to organs that don’t require transplant patients to take drugs, the power of genetic engineering means that the company might even one day create “enhanced organs.” For example, he said, it might be possible to edit the pig genomes to create “organs that are resistant to multiple pathogens” or even organs that age more slowly. As a proof of concept, he pointed to research in his lab at Harvard Medical School, the peer-reviewed results of which were published in Nature, where a simple genetic change made a bacterial species resistant to all known viruses. “Now we want to do it in pigs,” he said.

For the immediate future, the company will need to scale up, which will also require more capital, Curtis said. The company has enough runway for the end of 2026 and is is already in the process of raising more funds, he said. Curtis hopes the successful operation shows potential investors that the company is on track.

“What this first kidney transplant of a living person does is validate our whole approach,” he said. “And it’s going to allow us to not only bring the kidney forward but also bring forward the liver and heart in parallel.”

This article was first published on forbes.com