Research at the University of Sydney is hoping to revolutionise assisted breeding technology in agriculture that could one day make human fertility treatment less costly and more successful.

Key Takeaways

- In agriculture, there is a need for genetic selection, but current applications can be large in scale and expensive

- Australia is a leader in developing tech in agriculture

- Much of the technology used for human reproductive techniques was first developed for agriculture, including embryo transfer and sex-sorting sperm

Australia has been at the forefront of assisted fertility for decades, but the technologies that are being used today haven’t changed much since they were first applied.

Researchers in the Animal Reproduction Group in the School of Life and Environmental Sciences, part of the Faculty of Science at the University of Sydney, are looking to change that.

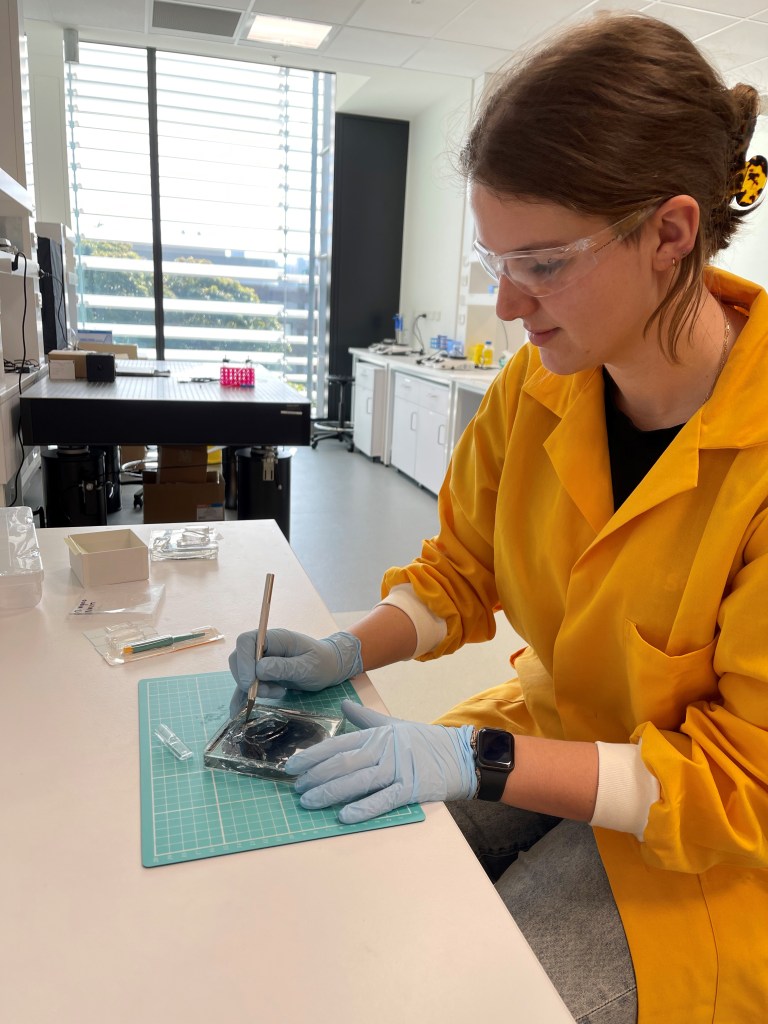

Katherine Seymour is a PhD candidate with the team that is looking at a novel technology using microfluidics and optical trapping for semen assessment and sorting with sheep.

In agriculture, Seymour explains, there is a need for genetic selection. However, current applications can be large in scale and expensive.

“While we’ve developed these reproductive technologies, a lot of people aren’t using them because the cost is so great,” Seymour says.

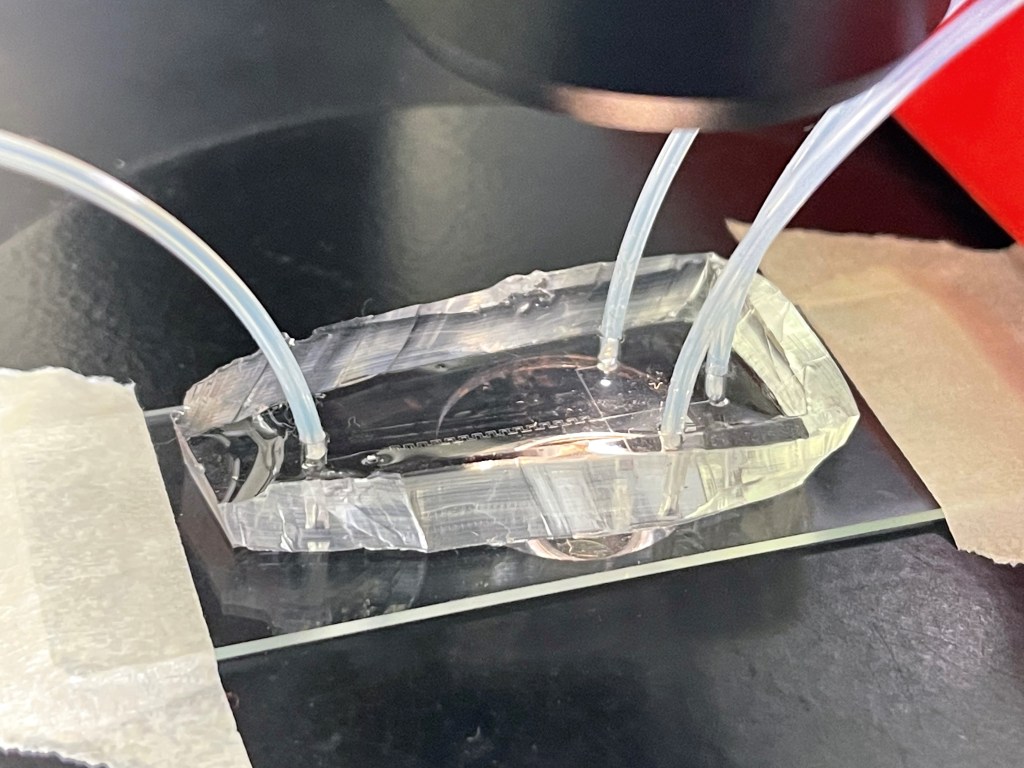

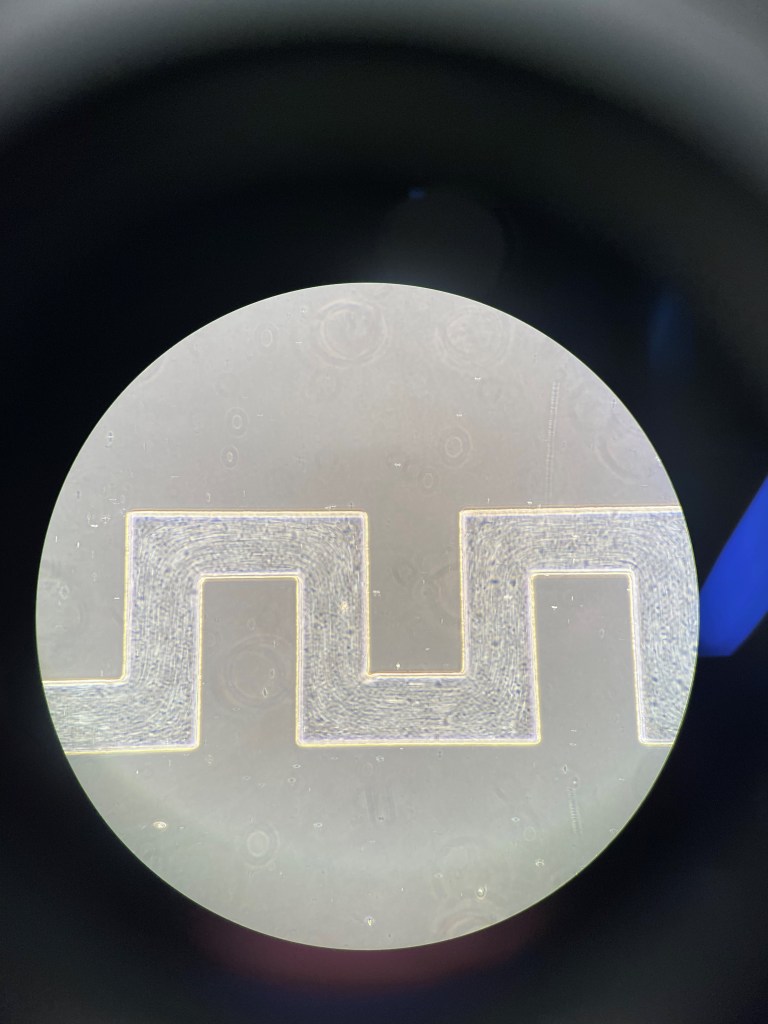

“One of the interesting things about our new technology is that it has the potential to miniaturise really complex equipment. The chips I am using are about the size of a playing card compared with the size of a desktop computer screen, previously. With our technology, you are working with less materials, you are not using the whole sample, less chemical reagents, so it’s cheaper.”

The team believes the technology they are working on, as part of an interdisciplinary project that also involves medical engineers and physicists from the University of Sydney Nano Institute, could potentially make it a lot more accessible and cheaper, but ultimately help to improve fertility results.

“This technology would allow livestock producers to assess the quality of semen from their animals more easily. Further it would facilitate production of sorted semen whether for quality or some other trait to enhance fertility and reproductive management.

“Long-term we are hoping to automate tech like IVF (In Vitro Fertilization) and ICSI (intracytoplasmic sperm injection) and that can be used in humans. It’s a way to make that a much cheaper process for people,” Seymour says.

“IVF and ICSI are very labour intensive. People handle the cells quite a lot, which can damage the cells. What we are looking at is having that completely computer driven, so you wouldn’t need someone physically moving cells, it would be done in a solution that mimics the female reproductive tract.

“We’re hoping the sorting process can help increase fertility. In males, the way the cell looks has a big effect on the fertility success of the embryo. The technology would use machine learning to sort out those normal cells and only inseminate with those cells so you would hopefully be really increasing the fertility from that process. The tech itself is a lot easier to use and manufacture, so the cost should also go down.”

Seymour says the research team has been working on the project for about three years.

“I’m coming in at the stage where we are doing the testing. I’m helping to develop those early checks and making sure the cells can survive. In the next few years, we’re looking at using machine learning to sort the cells and then there would be more time needed to commercialise, as you would need to introduce it into human trials.”

Much of the technology used for human reproductive techniques was first developed for agriculture, including embryo transfer and sex-sorting sperm.

“So if it works in sheep it is not a far jump to hope that it will work in humans,” says Seymour. “Australia is a leader in this area. We are very interested in tech in agriculture and a lot of the reproduction technology in the world has been established first in Australia.”