Ken King and Leonard Hall say we’ve entered “the age of the industrial flying robot.” Their company, Freespace Operations, claims to have cracked the code for 100 kg lifts.

We are “entering the age of the industrial flying robot,” say engineers Ken King and Leonard Hall who have cracked what many in the drone industry once called a holy grail: getting multiple autonomous aircraft to share a heavy load in flight.

The Freespace Operations founders’ breakthrough, known as cooperative lift, allows their flagship Callisto 50 drones to interlink and balance a common payload — lifting up to 100 kg.

It means they can take on missions that once needed a helicopter.

“This proves it can be done safely, reliably and at scale,” says CEO King. “We can now multiply the lifting power of a single drone while retaining all the flexibility of smaller systems.”

For Freespace — which began life in 2019 after years of defence-linked R&D — the breakthrough has already paid off, securing a multimillion-dollar contract with an international defence customer in the Asia–Pacific region. The company has delivered 29 Australian Government and Defence contracts worth more than A$9 million, alongside enterprise projects with energy infrastructure leaders such as Infravision and Enerven.

It’s the culmination of years of methodical engineering, solving one problem at a time, King says.

We’ve all seen drone swarms moving in unison to create lightshows. You’d think it would be easy to just hook them up to a heavy load and off they’d fly, like cartoon bluebirds helping Cinderella dress. Not so easy, apparently.

Cooperative lift

Irish-born engineer Ken King moved to Australia about 16 years ago, working on major construction and infrastructure projects for companies like Multiplex, Grocon and Leightons. Around 2013 he became fascinated by the emerging drone scene, and built his first multirotor craft from parts bought online. “It worked,” he says. “A flying robot.”

By 2016 he had earned his operator’s licence and was drawn into the fast-evolving Melbourne drone ecosystem. That’s where he met Leonard Hall, an electronics engineer with a background in defence research.

“The reason drones are so popular in line stringing is because people die every year flying helicopters stringing lines.”

Freespace Operations co-founder and CEO Ken King

A country boy turned radar and antenna specialist, Hall spent years designing radio systems and working on electronic warfare projects with the Defence Science and Technology Group (DST). While completing his PhD, he’d began experimenting with drones in his spare time — “flying robots are fun” — and quickly became one of the world’s leading flight-control developers.

He wrote much of the control software used in autopilots across the global drone industry, he says. “Before COVID, pretty much every industrial multirotor around the world was tuned by me.”

The two met in 2017, at the Avalon Air Show. After collaborating on a previous startup that didn’t take off, they launched Freespace Operations in 2019.

“I got sick of seeing people build aircraft poorly,” Hall tells Forbes Australia. “That’s where Ken and I came together to try and do something we could be proud of rather than trying to cover up other people’s problems.”

They teamed up to tune a large craft Ken was developing and came up with a craft that seemed unusually strong and stable, but it needed too much maintenance for them to take to market.

Back then, the norm in real-world conditions was that payloads above 10 kg were risky.

Their design specification called for 50-plus kilogram take-off weight, which was equivalent to a 26 kg payload.

“I said to Leonard, ‘I think we’ve got something special here,’” says King. “We knew that this was going to turn into what effectively is Industry 4.0 now, and the age of industrial flying robots.”

After having some success with the military, they were approached by Infravision, a Sunshine Coast startup [that would go on to raise $36 million in 2023], taking on the problem of stringing powerlines. King and Hall showed Infravision their craft but the company passed.

“Then they then spent 12 months looking at every aircraft around the world – a lot of them bigger than ours. They even bought a couple, and they had incident after incident. Then they came back and said, ‘We’d like to try yours,’” says Hall.

“We were actually able to do more with a smaller aircraft, without incident, than these seemingly more impressive-on-the-internet companies.”

Asked for comment, Infravision president of aviation Josh Williams said the company had conducted extensive due diligence on heavy-lift drone platforms worldwide. “And Freespace’s Callisto 50 was the first to deliver the reliability and consistent performance we needed at scale. When paired with Infravision’s proprietary aerial robotics and tension stringing system, the Callisto platform enables us to deploy power infrastructure faster, safer, and with greater precision in Australia and around the world.”

King says the Infravision partnership was key for them breaking out of defence and into industry. “Those guys absolutely trashed the aircraft, day after day, working in the Californian bushfires to re-string lines, the Californian Floods, heavy storms in Washington state. The aircraft powered through all of that.”

The next problem was tackling ship-based operations, creating what they describe as a “deck-mounted autopilot” — a beacon system about a metre wide, magnetically fixed to a ship’s deck. The beacon allowed their drones to lock onto the vessel as if it were another member of a formation. Unlike previous optical-tracking approaches, their aircraft could synchronise with the ship’s motion, they say.

Two years ago, they set to work on the cooperative lift problem. Multiple aircraft sharing a physical payload requires a level of coordination orders of magnitude higher, says Hall.

Each aircraft must mirror the other’s movement in real time, maintaining tight synchronisation without relying on a central ground controller, while the moving load can at times put enormous weight onto one craft while another’s load gets lighter.

Through all that, they need to behave “as much like a single aircraft as a swarm”.

According to Hall, that level of dynamic control wasn’t previously possible outside small indoor labs tethered to a PC. Freespace’s breakthrough came from combining advanced algorithms with aircraft robust enough to handle dynamic loads far exceeding their own weight.

“This is still an emergent technology,” says Hall. “People think drones are done, but we are still very young.”

A survey by the Australian navy found 90% of their helicopter payloads between ships were under 25 kg, and most of those were under 10 kg.

“If you carry these little 25 kg packages between two ships, five kilometres apart, they need to spool up this huge asset with three people in it and all of the maintenance and risk that goes along with that. All for something that the Callisto could handle.

“But then we get to that last 10% [above 25 kg] … If we’re able to employ swarms, we can take out the majority of that last 10% with an aircraft that costs less than the maintenance of a helicopter.”

Not to mention the risk to lives every time a chopper takes off.

“The reason drones are so popular in line stringing is because people die every year flying helicopters stringing lines,” says King. “It’s actually banned in a lot of countries, a lot of states. In South Australia it’s banned unless you get very special permissions. It’s that dull, dirty, dangerous, distant philosophy. You are removing humans from where they don’t need to be in the first place.”

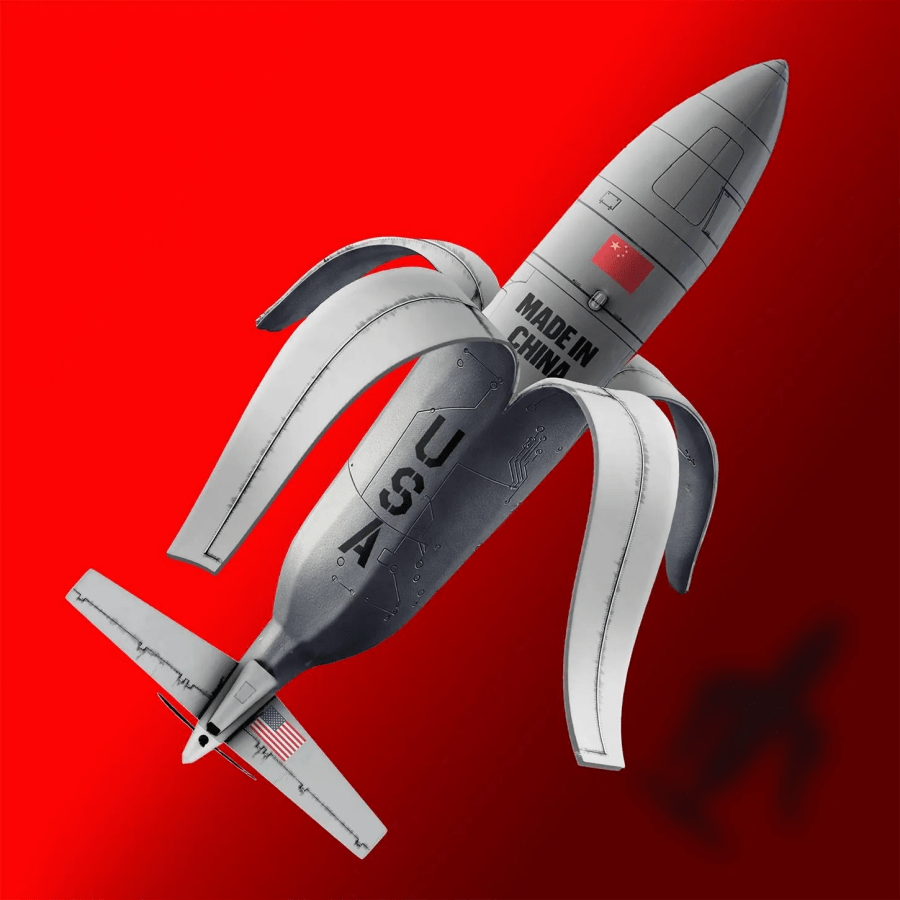

While Freespace has sold to all branches of the Australian military, it does not do weapons systems, but, like other drone companies, does not control what their craft are used for after sale, says King.