La Trobe CEO, Chris Andrews, a legal eagle turned long-term investment manager spoke to Stewart Hawkins sharing a broad-ranging historical look at investment markets, why, in that context he sees alternative, private assets as an innovative, solid place to put money, why middle America could prove a boon for Australian investors, why we shouldn’t bash the banks too hard and outlines his rather pessimistic reason for pragmatic market optimism.

This story appears in Issue 19 of Forbes Australia, out now. Tap here to secure your copy.

As an investor, what have been your long-term fundamental thought processes?

Probably the most important thing is keeping it simple. It’s got to be sustainable. It’s got to be something where you get a really good understanding of what you’re investing in, where you get a good sense of the dispersion of outcomes that are likely to occur on a reasonable basis. Sometimes, the theoretical portfolio optimisation models fail in execution.

We’re thinking about investing in assets that you can deeply understand and have a good sense of how they’re likely to perform across the cycle.

What we’re trying to do here for our investors, and certainly where I put my money, is finding places to invest where I can be really confident about the long-term risk-return potential.

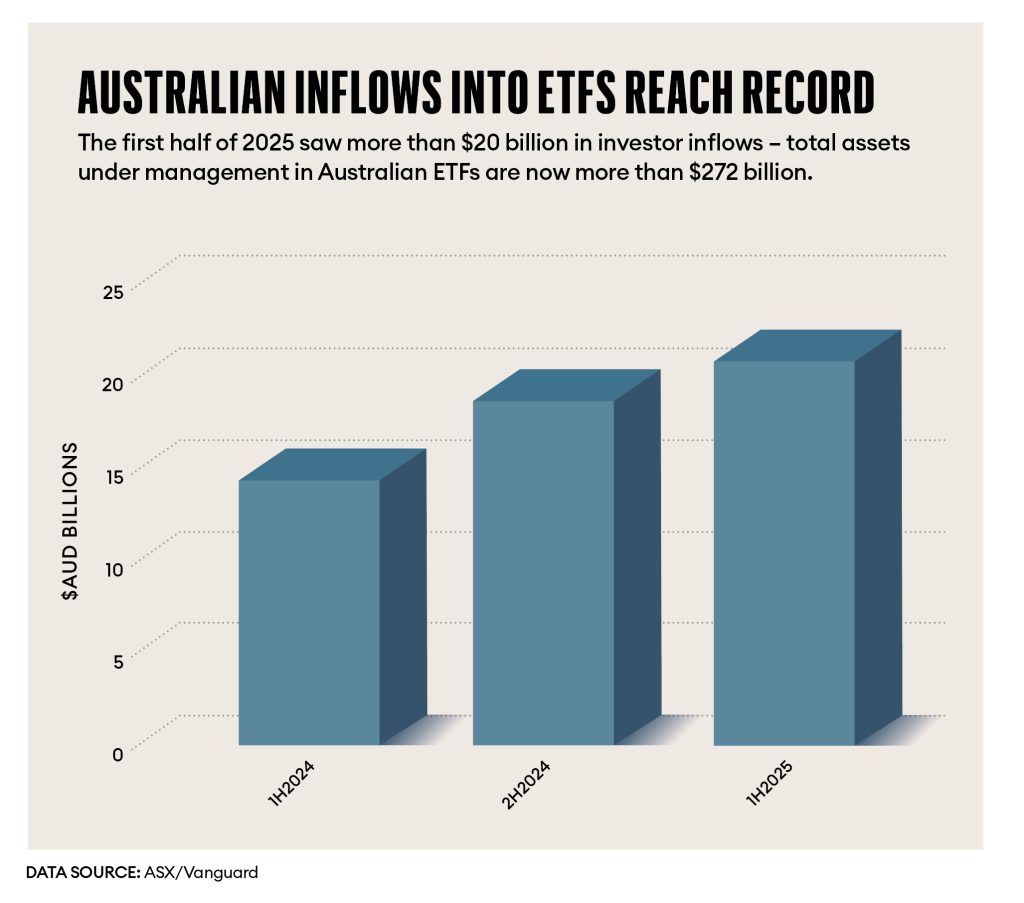

We’ve seen over the past 20 years the really aggressive rise of passive forms of investment. That’s making it very difficult for active managers because passive investing is, on average, outperforming active managers net of fees, now, very consistently. For folks who are interested in the stock market, there are very easy passive vehicles to access, which are low-cost and terrific, and you think of the likes of Vanguard and BlackRock and so on.

“There’s no bonus points for degree of difficulty,” an awesome quote from Warren Buffett, which we always remind investors of when they’re talking about complex and convoluted investment strategies, tax optimisation investments. That’s all good, but if you don’t understand it…

How different is today’s market? What dynamics are at play?

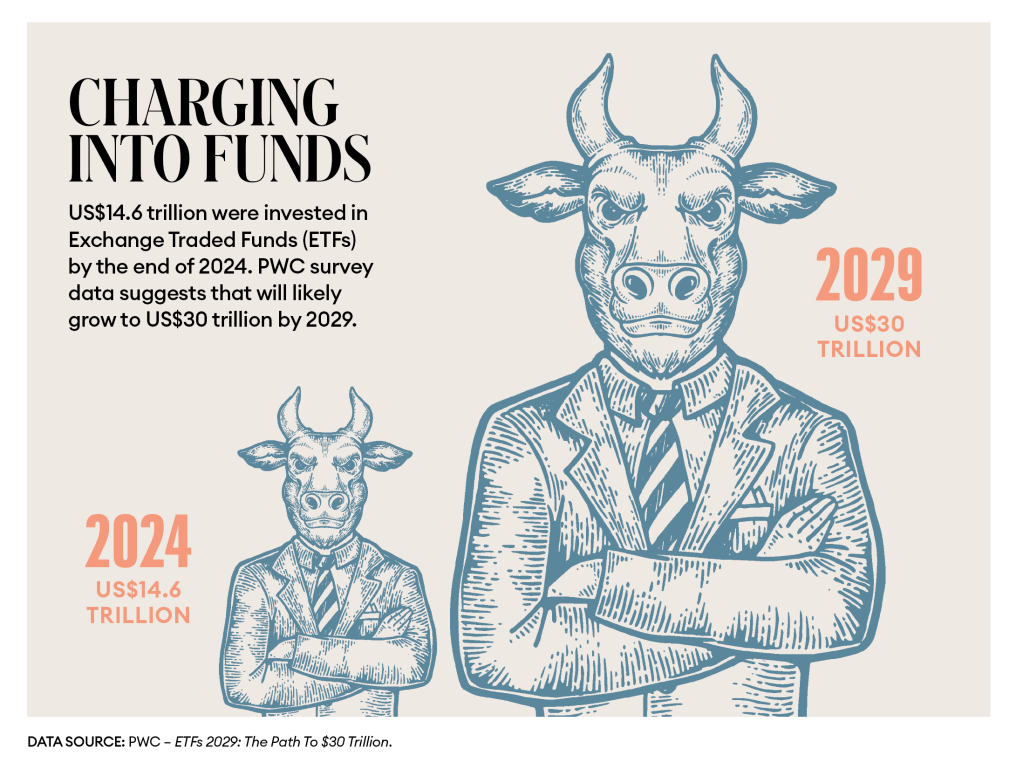

The biggest thing [is] the rise of passive investment. And on the other side of the spectrum is the fact that the world is just really waking up to the power of what are described as alternative investments or private markets.

If you go back to the turn of the century, 2002, say, alternatives were just 5% of global assets under management. It’s now 15% of global assets under management, so it has tripled. As a proportion of overall assets under management [AUM], that’s growth from two trillion [USD] to $US25 trillion.

That trend is continuing. Most actuarial projections now have it hitting around $US60 trillion by 2032, so 20% of global AUM. Put that in context, that’s more than the entire global market in 2002.

But why is that going on? These asset classes are offering what traditional asset classes often aren’t now: diversification, lower volatility, predictable cash flow, and a more consistent return profile. You think about private credit, it’s having its moment. It’s maturing, and it’s still, here in Australia, got some maturation to go. It’s attracting capital, and it’s getting all of the appropriate attention from the big institutional investors, increasingly from retail investors and now, appropriately, from regulators, as well.

How do you define an alternative investment?

One of the frustrating things I found when I moved from the world of the law [is that] you can always get the definition of the term in question. There will be a section of the act which will have the definitions, and that’s very helpful and handy. Unfortunately, investment markets don’t come so neatly labelled, but broadly speaking, alternatives are those forms of investments outside things like stocks, bonds, and cash. Now you can debate whether, for example, property, which people would say, “Well, hang on, that’s a very traditional asset class.” Yeah, okay, but it’s not in traditional portfolio theory as an asset class.

Property is generally treated as an alternative investment infrastructure, private credit, or private equity; all of these sorts of things are regarded as alternative investments. There will come a day when we probably look at that word, alternative, and say, ‘alternative to what?’

I prefer private markets, suggesting unlisted or private market-type investments. That probably points to one of the fundamental characteristics of these asset classes, which is that you expect to see, across the cycle, less of the greed/fear factor playing through. It’s a steadier return profile over time.

If you look at the gyrations in the US stock market, I think it lost, I’m speaking in rough numbers, but between the start of the year and the peak of the Liberation Day panic, I think it lost 10%. And I think, since then, it has regained all that ground and grown another 10%. Now, does anyone think the investment fundamentals of the world actually gyrated by 25% in that period?

If you were a private market investor, you probably experienced little to no volatility through that period. I think that’s one of their great attributes.

But there is a potential for volatility and risk in alternative assets.

Investment markets are trade-offs. It is true that the risk of poorly executed private market strategies is that folks aren’t disciplined in their valuation of assets. There’s potential for abuse in every form of investment, and if there’s not proper discipline around those processes, then that is an issue, but the abuse of something by certain operators doesn’t mean that the fundamentals are wrong. It just means you’ve got a bad actor there in the market that you’ve got to be cognisant of.

What’s the cure to that as an investor? How do you separate a bad actor from a good actor? You look for transparency. If we look at what’s going on in the Australian market now, there has been a proliferation of corporate private credit operators. These are businesses that are set up. They raise capital from investors, and they invest in loans to corporates, direct loans, or they participate in structured finance transactions, leverage buyouts or RMBS [Residential Mortgage-Backed Securities], mezzanine notes [debt that ranks behind senior debt but superior to equity] and these sorts of things.

There’s nothing wrong with that form of investment, but if you’re not properly disclosing when one of those loans is impaired, if you’re not properly marking an impaired loan to market, if you’re not taking into account that impairment and you’re continuing to hold that at full value at par, then you are doing a disservice to your investors. When you look at the review that ASIC is conducting of that sector at the moment, that is the very issue, among others, that ASIC is honing in on.

It is right to say that what we want is a well-regulated, well-ordered market. We want operators with very clear, transparent approaches to valuation of assets, to dealing with defaulting loans, and to the use of the capital that they raise, as well. All of those things are true, and we are enormous supporters of the need for a significant regulatory review.

What would it take to upset the “investment fundamentals of the world”?

Has there ever been a time in history when folks living in that time of history have felt like everything is okay?

I remember when The Terminator movies came out, and what was sitting behind The Terminator? The fundamental conviction we all had was that eventually the USA and the USSR would end up in a nuclear exchange that would be the apocalypse. And we were all wondering if we’d make it to the year 2000. We’ve had all sorts of ups and downs since. We’ve had the early ’90s recession. We’ve had the tech wreck and boom. We’ve had 911 and the misadventures in the Middle East. We’ve had the global financial crisis. We’ve had the rise of The Magnificent 7. We’ve had a flaming global pandemic.

It did cause a bit of volatility in markets, but if we were having this discussion in April or May of 2020, and I was sitting in Victoria in what was, for a period of time, the most locked-down city in the history of the universe or something, things were looking black. If I said to you that five years later we would be sitting here and the unemployment rate would be 4.2% and inflation would be back within the target range, and we’d be, of course, looking at productivity and wondering about declining birth rates and thinking about some volatility in the Middle East, and, “Gosh, we haven’t quite sorted out China in the South China Sea,” and et cetera, et cetera, you’d go, “Well, that sounds like a pretty benign view of the world five years from now, Chris. Oh, I think you’re on the wacky tobacky.”

I am not saying that bad stuff can’t happen, but I’m saying… spare me the notion that today is the most difficult and concerning and worrying of times because I’ve lived long enough to see there’s never a time when everyone is going, “Things are pretty right, at the moment.”

You’ve got to take a balanced view of these things; otherwise, you’d never do anything. Canned foods and shotguns would be the headline of this article.

With institutional investors dominating the traditional assets. Where are the opportunities now? In Australia, we do have a narrow market. So, where do you look?

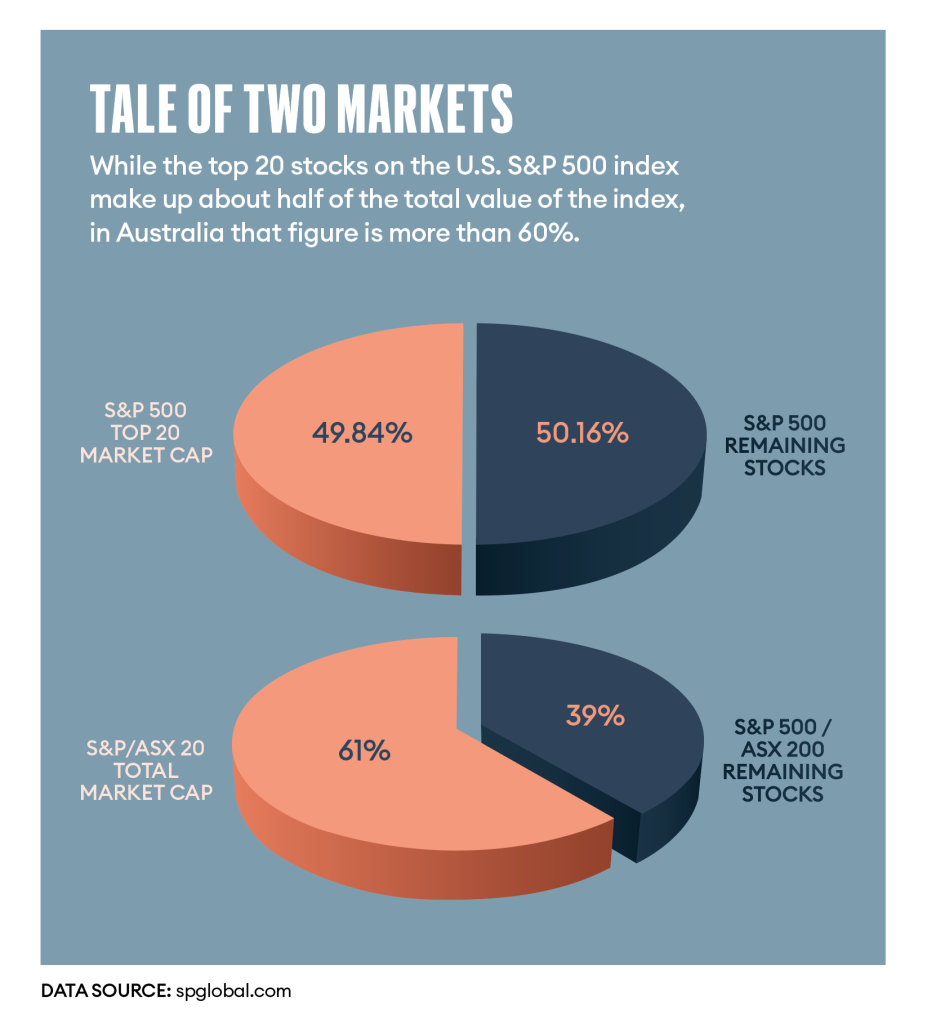

Equities markets are dominated by passive funds, dominated by the big institutional investors. It’s incredibly concentrated. In the US, you’ve got the Magnificent 7. Here in Australia, really, you’ve got the Big Four banks. It’s complex for investors to get diversified exposures.

By contrast, you’ve got private markets, and nothing’s perfect, but what you get in private markets, as a general rule, in the property market and private credit, always, where it’s well run, is you get investors making decisions based on investment fundamentals. They’ll be assessing the cash flows of a borrower. They’ll be assessing the future economic outlook for a borrower. They’ll be making a really sensible credit decision.

There’s a spectrum of risk-return profiles you can attract in that part of the market if you want a diversified portfolio from a yield and risk return perspective, but you are getting folks making proper, consistent investment decisions. What do we do? We’ve got a US private credit strategy, and we’ve got a real estate private credit strategy here in Australia.

Let’s start with real estate private credit. We’ve been doing that since 1952. So that’s putting together what is really the only one of its kind in Australia. It’s a very granular portfolio of residential and commercial mortgage loans. Average loan-to-value ratio is sort of 64%. If we look at our 12-month term account, which is the flagship product, that’s $11 billion in AUM, and we’ve got 11-12,000 individual loans in that portfolio.

It’s an incredibly diverse portfolio. No one is just investing in a loan because there’s an algorithm saying that this borrower might be a good risk or because we’ve got to rebalance portfolios and tip into this borrower because they’re X% of market cap. It’s a fundamental bottom-up credit decision that’s made with respect to that borrower.

What we found is that sort of portfolio construction performs absolutely beautifully through the cycle.

What about offshore?

The US private credit strategy is leaning into that corporate credit proposition. We looked at the Australian corporate private credit space. It felt a little thin. It’s not a particularly deep market in Australia, and it’s still immature. Conceptually, we like the asset class. Conceptually, we think Australian investors should have access to it, but we were looking for a different way to participate in that market, and we saw the US mid-market as being the part of the world that we wanted to focus on.

Let me unpack that. Really, since Donald Trump, both sides of politics have embraced this notion that, since the 1990s and all of the offshoring and outsourcing, a whole chunk of America was left behind. If both sides of politics hadn’t ignored what we, disparagingly, referred to as the flyover states for 30 years, there wouldn’t be a Donald Trump. Right?

What you reap, you sow. Whatever folks think about Donald Trump, he’s a symptom, not a cause.

What both sides of US politics have realised is that middle America, which is still, despite the fact that it was overlooked for so long in favour of the really big… the Apples, Googles, et cetera, et cetera. This middle American economy, if you were just to excise it and cut it out on its own, is the third-largest economy in the world, after the US as a whole and China. It’s extraordinarily broad and deep.

It’s these businesses which are often still family owned [and] in many cases, staggeringly profitable businesses. They could be generating EBITDAs of three, four, or 500 million US dollars, and there are tens of thousands of these businesses all over the US. And you would never have heard of them here in Australia. And what are they doing? They’re doing everything. They’re providing janitorial services to factories. They’re catering companies. They’re cleaning. They’re small-scale manufacturers of apparel.

If you think of everything, both sides of US politics are focused on now, it’s rebuilding that part of the US economy. There are any number of initiatives designed to pour the fiscal spigot of the US absolutely at that part of the economy. And that includes things like tariffs, which are designed to protect those smaller companies against what they see as unfair competition from China. That’s what the whole US is focused on.

We see that as being, [for] the next 20, 30 years, a wonderful thematic for Australian investors to participate in, and by investing in loans to those sorts of corporates, really conservative loans. We’ve done this as a partnership with Morgan Stanley because, for us, we think about that and say, “We could set up an office in the States, in the Midwest or somewhere in the US, but we just wouldn’t get access to the right deal flow.” We partner with Morgan Stanley so that we can lean into the deal flow that they get access to and build another really granular portfolio of high-quality assets that will deliver. So, that’s currently delivering a tick over 8%, which is just a wonderful return for investors for such a conservative exposure to US mid-market private credit.

What is the role of the banks in terms of their lending? What’s their influence in this market in Australia?

I have the unfashionable view that our banks in Australia, actually, across time, have done a pretty good job. They are really effective in serving the vast bulk of the market, call it two-thirds of the market in Australia. They serve it really well. And if you’re a vanilla borrower, you’ll get good service from the banks, and that’s appropriately the case.

Where significant space has opened up over the last 30 years or so is in borrowers who are more complex. On the one hand, if you’re thinking very granular, who aren’t easily automated, and if you’re thinking of larger and more structured loans, are difficult for banks to absorb onto their balance sheet given capital requirements that have been imposed post-global financial crisis and imposed for good reasons. That’s sort of, if you like a structural driver that will continue to see the private credit sector grow, but the banks are still wonderful businesses here in Australia.

I know we do like to tear them down, but there’s something worse than having strong, profitable banks, which is having weak, unprofitable banks. The Australian payment system seems to be at the cutting edge of what’s going on around the world, generally, and I think we should be very careful in kicking them too hard.

What keeps you awake at night?

Productivity and house prices. House prices, if I start there, it’s not that we’ve left a whole segment of our population out of jobs or left behind, in that sense, but we’re risking leaving generations of folks, including my four kids, out of the housing market. That is the sort of thing that can rip a hole in the fabric of society. While people will fret and mutter and say how difficult it is, it’s actually not that difficult if we really treat it with the seriousness that it deserves.

Productivity, the topic du jour now. We’ve been talking about it for 10 years because it’s been an issue for 10 years. To think that productivity is now languishing at 2016 levels is embarrassing for us all. It’s fascinating to think about what that means, but we’ve got a productivity summit that the government is chairing now and, amusingly, will the productivity summit actually produce anything? What will be the dividend of the productivity summit?

Based on recent outcomes, one would be excused for being a little bit pessimistic. There’s got to be a hunger in Australia to want to do things better, and there’s got to be a hunger to embrace change. We are spending a lot of time… for example, in our conversations around artificial intelligence, talking about our fears that AI might come in and it might change things and might rule us all. Fair enough to spend a bit of time there, but there are so many really easy implementable use cases for AI that will just make every employee so much more efficient, so much more effective and will open up jobs by dint of doing that.

How about we in Australia just choose three or four really simple use cases in every business and get cracking right now?

Do you know what that boils down to? It’s just one thing. It’s hunger. We are very comfortable here. If you’ve got hunger and drive, you’ll work it out.

What is your best piece of advice for our readers?

Focus on the signal, not the noise. If you think about 2025, it has been a roller coaster for investors. Floods of data – we’ve seen US inflation, GDP growth, job numbers.

For Australian investors, the challenge is clear. You want diversified portfolios of assets that you understand. Think about all the noise. Think about the US in particular – it’s too big and too important to ignore.

This is not the worst of times. It’s probably not the best of times either.

This article represents the views only of the subject and should not be regarded as the provision of advice of any nature from Forbes Australia. The article is intended to provide general information only and does not take into account your individual objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance. You should seek independent financial and tax advice before making any decision based on this information, the views or information expressed in this article.

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.