Crispr’s ability to cut genetic code like scissors has just started to turn into medicines. Now, gene editing pioneer Jennifer Doudna wants to build an entire ecosystem to bring these treatments mainstream.

Soon after KJ Muldoon was born in August 2024, he was lethargic and wouldn’t eat. His worried doctors realized his ammonia levels were scarily high. Further tests showed the infant had a rare metabolic disorder—the kind of diagnosis that’s often a death sentence.

A team of researchers from Crispr pioneer Jennifer Doudna’s Innovative Genomics Institute and doctors from the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia and Penn Medicine began sprinting to create a custom treatment to fix Baby KJ’s DNA, using Crispr-based gene editing. Within just six months, they designed the therapy, got lightning-fast approval from the FDA and manufactured it. Baby KJ received his first infusion on February 25, 2025, and today is a healthy one and a-half year old.

It was perhaps the most significant milestone yet for the relatively new field of gene editing, which Doudna helped originate more than a decade ago. But even she was floored by how quickly the team of physicians and scientists were able to spin up the life-saving treatment.

“I mean, I’m stunned,” Doudna, 61, told Forbes. “I know the technology well, but I’m still stunned.”

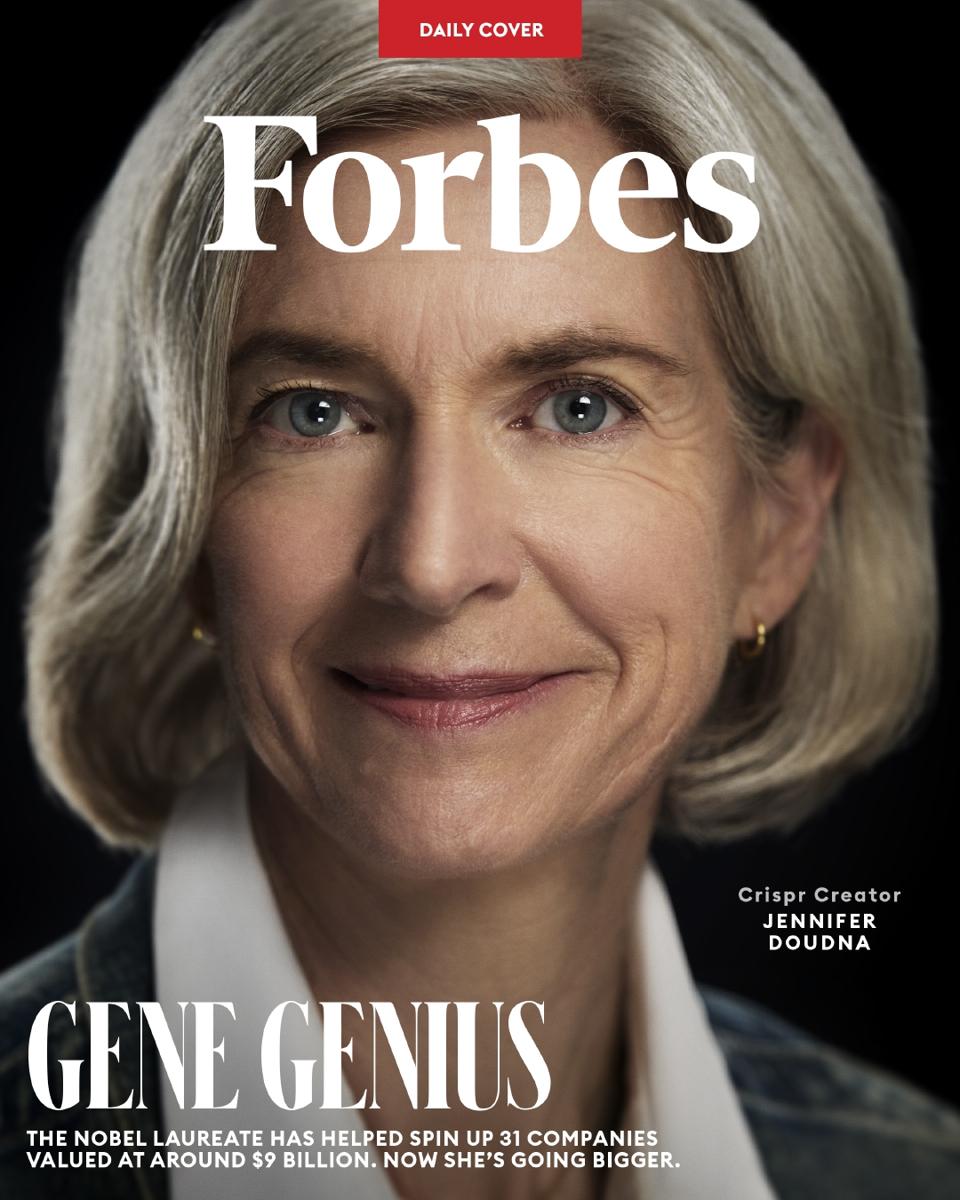

To say Doudna knows the technology is an understatement. Her research laid the scientific foundation for gene editing, using Crispr as programmable molecular scissors to cut and slice up genetic code. She and her collaborator, French biochemist Emmanuelle Charpentier, won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for their work on Crispr. Her lab at the University of California, Berkeley has become a crucible for students starting Crispr-related companies. In 2015, she founded the IGI, a joint effort between UC Berkeley, UCSF and UC Davis to use Crispr in applications across health, agriculture and even climate. Funded largely by philanthropists like the Li Ka Shing Foundation and the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative, it currently has an annual budget of around $40 million.

To date, Doudna and the Institute have helped spin out 31 companies that are now valued at around $9 billion and employ more than 2,500 people. She is a cofounder of seven of them. For these achievements, Forbes has named Doudna to our list of America’s 250 Greatest Innovators.

“Jennifer is calm and focused at all times, and then, when the time is right, Navy Seal Jennifer comes out and that Navy Seal Jennifer, goes, ‘Folks, here’s the mission and here’s why it’s the right one and here’s how we’re going to do this,’” said Fyodor Urnov, a UC Berkeley professor of molecular therapeutics and the IGI’s director for therapeutic R&D.

So far, commercializing Crispr has proven to be really, really hard. Crispr companies across the board have been hit with scientific setbacks, layoffs and sharp stock declines. The first startup to come out of Doudna’s lab, Caribou Biosciences, launched in 2011, went public with big hopes a decade later, and has since seen its stock fall 91%, giving it a market cap near $150 million. Editas, for which Doudna is one of the scientific founders, laid off 65% of its staff and shelved its lead gene-editing program for sickle cell disease in December 2024. And in one of the more spectacular blowups, Tome Biosciences, which spun out of MIT, laid off almost all of its staff in 2024 and is no longer operating after raising more than $200 million.

Part of the challenge has been the downside cost of all the Crispr hype. “Crispr was the AI of 2018,” said Janice Chen, cofounder and chief science officer of Mammoth Biosciences. The company spun out of Doudna’s lab, where Chen was a student, in 2017. “Jennifer had warned us about the hype cycle,” she added. “There’s huge expectations. Then it takes longer and costs more money.”

Venture funding for U.S. gene editing companies rose steadily from $2.4 billion in 2016 to a peak of $12.2 billion in 2021, according to data from VC database PitchBook. By last year, investment in the sector had fallen back to $5.2 billion, according to PitchBook data.

There has also been a years-long patent dispute over the early Crispr discoveries between the University of California and the Broad Institute, whose scientists published on Crispr around the same time as Doudna. She said that the dispute, which still hasn’t been fully settled, has “zero” impact on the work she’s doing now.

And yet, as the Baby KJ case shows, the potential for the technology to have dramatic impact on our lives remains. In late 2023, the FDA approved the first Crispr-based therapy, for sickle cell disease, from a partnership of Vertex and Crispr Therapeutics, a company cofounded by Charpentier—at a list price of $2.2 million per patient. Big pharma is starting to pay attention. Last summer, Eli Lilly acquired Verve Therapeutics, which is working on developing gene editing medicines for cardiovascular disease, for $1.3 billion. And while none of the companies in Doudna’s ecosystem has gotten a drug through FDA approvals and to market yet, Mammoth signed a deal in 2024 with biotech giant Regeneron for which it received $100 million upfront, including equity investment. Mammoth was last valued at $1.4 billion.

Doudna’s next act is trying to make sure that Crispr’s potential finally pays off. “I don’t want it to be a curio, a topic of academic interest that maybe impacts a few people on the planet, but for the most part doesn’t intersect with the real world,” she said.

Core to her plan is the IGI: Doudna plans to raise $1 billion for the institute to support a budget of $100 million a year for the next 10 years to set up the next generation of scientists. With that funding, she hopes to start making personalized gene editing a more widely available treatment, to use Crispr to create therapies for common diseases like cancer and even to find applications in agriculture and the environment — all in a way that’s cost-effective.

“My biggest ethical concern is actually access and inequality,” she said. “We really want to make sure that the work we’re doing ultimately benefits everybody, not just a few wealthy individuals.”

Doudna, who grew up in Hawaii, realized she wanted to be a scientist in sixth grade after reading James Watson’s book about how he and Francis Crick discovered the double helix structure of the DNA molecule. She first made her name in science as a preeminent researcher of RNA after getting her Ph.D. at Harvard. She joined UC Berkeley in 2002.

Her work on RNA led her to Crispr. Even before Doudna published her groundbreaking paper in 2012, her student Rachel Haurwitz launched Caribou to turn new gene editing technologies into medicine. It was so early then that when they spoke to investors in Silicon Valley, no one had heard of Crispr, let alone wanted to give them money. “It sounded so big and ridiculous that people didn’t think it was real,” Haurwitz, the company’s CEO, recalled.

Other startups that Doudna founded in conjunction with former students, like Mammoth, followed. Scribe Therapeutics, also started in 2017, is developing new Crispr-based treatments for cardiovascular disease, the leading cause of death globally and a hot area of research for gene editing. Azalea Therapeutics, founded in 2023, focuses on a way to reengineer patients’ cells inside the person’s own body (“in vivo” in the scientific lingo) rather than having to take them out, engineer them and then reinject them—an advancement that could have a big impact on cancer treatment. It launched out of stealth last November with $82 million in funding led by Third Rock Ventures.

“I don’t want it to be a curio, a topic of academic interest that maybe impacts a few people on the planet, but for the most part doesn’t intersect with the real world.”

To launch the company, cofounder and CEO Jenny Hamilton, who had been a researcher in Doudna’s lab, went through IGI’s inaugural Women in Enterprising Science program in 2022. That included $150,000 in support for the first year and the chance to receive up to $1 million in seed funding from a separate foundation after that. She credits Doudna’s belief in her: “She gives people the confidence that they know more than her in their area, that they are the expert and they should own it.”

Now, Doudna has a new idea: a modest-sized fund, starting in the tens of millions of dollars initially, that would combine VC funding, philanthropy and university resources to make early-stage investments in gene-editing companies. She’s talking with financial advisors about the idea now, and thinks that it might be especially useful for more risky projects, like those in the agricultural space.

Doudna is also building off the successful treatment of Baby KJ. Last July the IGI set up a new Center for Pediatric Crispr Cures with $20 million in funding from the Chan Zuckerberg Initiative. Its goal is to develop personalized Crispr treatment for eight children with severe genetic immune disorders and metabolic diseases. IGI executive director Brad Ringeisen would like to expand to 1,000 diseases, including more complex problems in the brain and kidneys, a move that he figures would require $100 million to $200 million.

“The treatment of the child in Philadelphia has made pretty much everyone a believer,” said Urnov, IGI’s director for therapeutic R&D. “We have no excuse to slow down.”

But regulation has been a major hurdle. Genetic diseases are exceptionally complicated because they almost never look the same in everyone. That makes the traditional regulatory approval process complicated because, in theory, each mutation would require separate clinical trials.

Now, the FDA is weighing a new way to assess these kinds of therapies. In November, FDA Commissioner Marty Makary and Vinay Prasad, the FDA’s chief medical and scientific officer, published a New England Journal of Medicine paper that proposed a new way for drugmakers to gain approval. That might allow drugmakers to adapt a gene editing treatment for various mutations of the same gene once they’ve been through a small trial.

“The treatment of the child in Philadelphia has made pretty much everyone a believer. We have no excuse to slow down.”

Already, Doudna and Urnov have helped launch a new company, Aurora Therapeutics, to expand gene editing’s potential to treat rare genetic diseases based on this emerging regulatory framework. Aurora came out of stealth in January with $16 million in funding from Menlo Ventures. “I think we can make this a commercially successful endeavor,” said Aurora CEO Edward Kaye, who spent a decade as an executive at Genzyme, the biopharma company acquired by Sanofi for $20 billion in 2011. “Gene editing is not fulfilling its potential if we cannot get these drugs to patients that need them.”

While medical treatments may take years to be developed, tested and approved, at least there’s a clear path to commercialization. Some of IGI’s programs for targeting climate change seem even more futuristic. Consider its project to reduce methane—one of the most potent greenhouse gases contributing to climate change—by using Crispr to edit the genes of cows’ microbiomes so they don’t burp and fart out as much methane. Based on research from UC Davis and funded by a $70 million grant from TED Audacious, IGI is testing the idea on 24 calves. Ideally, Doudna said, it could be done with a one-time treatment and maintained with very small adjustments to the cows’ diet, keeping it affordable for farmers. It’s not yet clear what the business model would be.

This is all a long game. Reed Jobs, whose VC firm Yosemite focuses on cancer and who sits on IGI’s board of directors, compares Doudna’s potential impact to that of Marie Curie, who won the Nobel Prize for her work in radiation. “There’s no way that Jennifer’s impact is all going to happen in her lifetime—or in my lifetime for that matter,” he said.

Doudna knows her best chance at having that kind of legacy is to foster the next generation of scientists and startups, beginning now. “The best that I can do in terms of making the next breakthrough or discovery is not to do it by myself, but to enable other scientists to do it,” she said.

This article was originally published on forbes.com and all figures are in USD.

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.