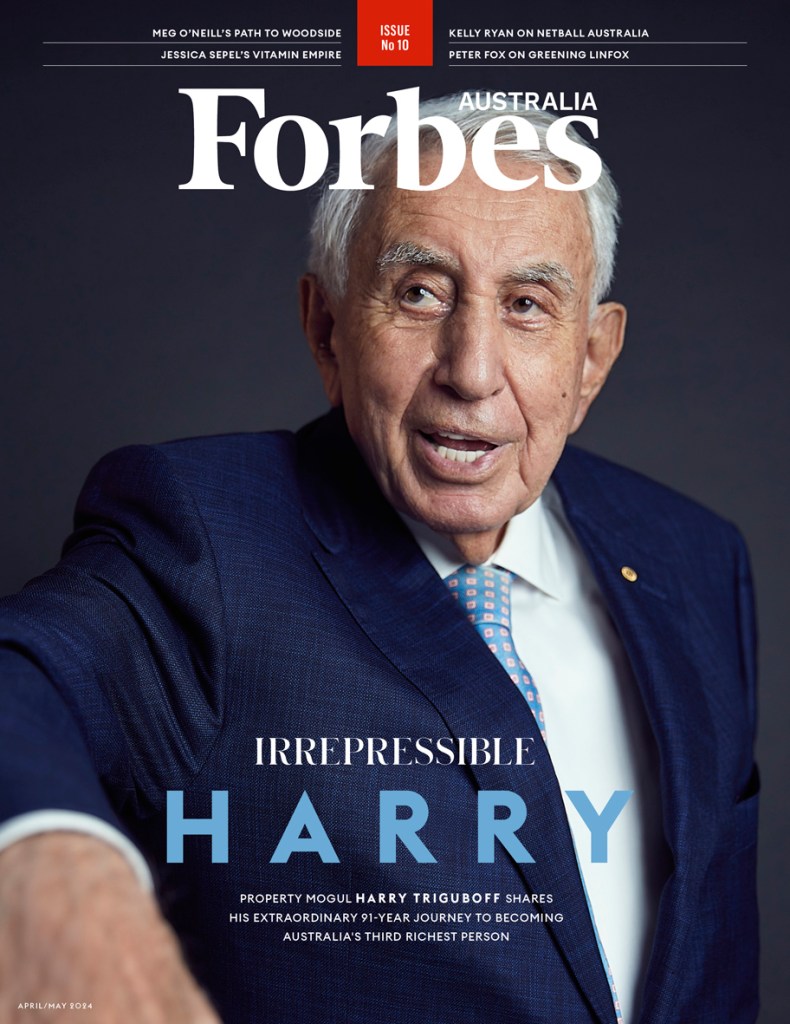

At 91, Australia’s third-richest person Harry Triguboff is still waiting for everyone else to see things his way. He explains how he has left his rivals in the shade, why he just keeps getting better and his secret for a long life.

Join us at the Forbes Australia Icons & Investors Summit to hear directly from Harry and Australia’s top business and wealth experts. Tap here to secure your ticket.

This article was featured in Issue 10 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

Good doctors. Very good doctors. That’s the secret to his longevity, says Harry Triguboff, 91, launching into the story of how just two weeks earlier (in early March this year) he was told he had maybe a day to live. There was no time to call the family bedside.

Water had been welling around the heart of the then 90-year-old who founded Australia’s largest property developer, Meriton Group, and is estimated to be worth $25 billion.

“And my face grew like that,” says Triguboff, motioning a ballooning head with his hands. “And I don’t look at the bloody mirror. Who looks in the mirror at my age? And the woman in the house, she saw it and got frightened. She took me to the hospital quickly, and they looked at me and said ‘50-50’,” he laughs with his thick Russian accent evoking a country in which he has never lived.

“The doctor told me I think we might succeed, we might not. And even if we succeed, you might have to be in a wheelchair, so do you want us to do away with you or keep you alive? I said, ‘Try to keep [me] alive,’” he chuckles. “In two hours, the bastard fixed it. So the doctors today are very important. The problem is the pills can be a great help but also be a great problem. It’s like I talk to the council, and I say, ‘Your rule might have been right when you wrote it, but things change.’ The body changes. The pills are the same.”

The next night, Australia’s third-richest person was back doing “the sheets” in his hospital bed. He motions a pile of paperwork about 15cm high – his weekly ritual of examining the numbers across all aspects of the company he founded 61 years ago – without a computer in sight.

The China-born Russian Australian who did more than any other to reshape the antipodean dream – from owning a house with a backyard into something more like an apartment with a sauna, a decent balcony and a daycare centre – was back to work. Three per cent of Sydneysiders live in one of the 78,000 apartments Triguboff has built since he got his start constructing brick-box walk-ups in the city’s suburbs in 1963.

As his fortunes rose, so did the quality of his product, the size of his buildings, the affluence of his customers and the influence of the man. Banks almost broke him in the 1970s, and he vowed to free himself from them. Meriton pioneered build-to-rent and serviced apartments. So, when other developers stumbled during the global financial crisis, it powered through, and Triguboff only got richer.

He led the way in taking on councils and planning ministers to allow more dense development – usually winning. And with Australia now facing an ever-deepening housing crisis, he’s got 4,500 apartments under construction and 5,000 more in the pipeline. Even if bureaucratic restrictions were to gum up the industry, forcing rents and property prices to skyrocket, as Australia’s largest landlord – with a private rental portfolio of 5,4000 apartments and 4,000 more under management – he’s got himself into a position where he just can’t lose.

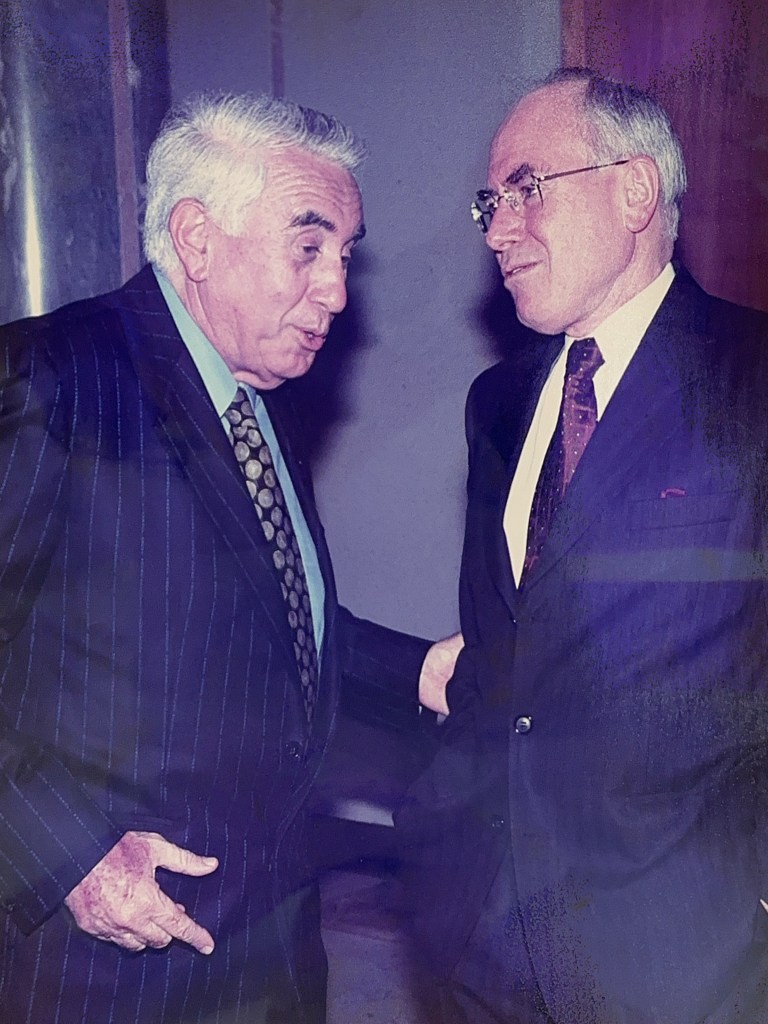

As he approaches, short and hunched, down the corridor of his 12th-floor office in Sydney with unusually warm air-conditioning – “Mr Triguboff feels the cold” – staff attempt to anticipate his requirements. He leads the way into a boardroom with walls filled with pictures of his progeny, his many birthday parties, him with US presidents [Bush snr and Clinton], and prime ministers of Australia and Israel. And it is clear how much Meriton and its 100% owner are one and the same.

Before he begins talking about his astonishing journey from 1930s China to being the world’s 112th richest person, he wants to see the last issue of Forbes Australia to understand what we’re going to do to him. “Wow. Designing a Juggernaut,” he reads of Canva’s Cameron Adams. “It’s an internet company,” a staffer says helpfully.

“That doesn’t mean anything to me,” says Triguboff, who still does all his work on paper but saw the future before anyone else and, with equal measures of charm and obstinance, scaled his fortune one brick at a time.

Rickshaws and tiny feet

Triguboff’s parents, Moshe and Frida, moved to China in 1916, fleeing antisemitism in Russia. Harry was born there in 1933 and grew up in Tianjin, the port gateway to Beijing that was divided into concessions held by the major European powers.

Asked what his strongest memories are of those days as a small child, he cites the poverty; that the rickshaw drivers ate a lot and died young; and that the old women walked strangely. “In the city, many Chinese women had their feet bound. They would walk on their heels. It was very strange.”

Tianjin was invaded by Japan in 1937, a moment considered by some historians to be the actual start of World War II, two years before Hitler invaded Poland. However, the Japanese left foreigners largely unmolested in their various concessions. “First of all, we had to learn Japanese,” recalls Triguboff.

After the attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941 British, American and French nationals were rounded up, while the Russians were left alone by Japanese masters eager not to antagonise the Soviet bear to the north. It allowed Moshe Triguboff to expand his little business trading in textiles.

Triguboff has previously told of accompanying his father on visits to Japanese leaders to discuss business. He recalls no hardships during that period. “We had a very good [Japanese] general. He said Japan can’t win the war, so he took a long time to lock them [British and Americans] up. I always wanted to find out what happened to the general from Tianjin. He was a lovely guy.”

Bronzed Aussies

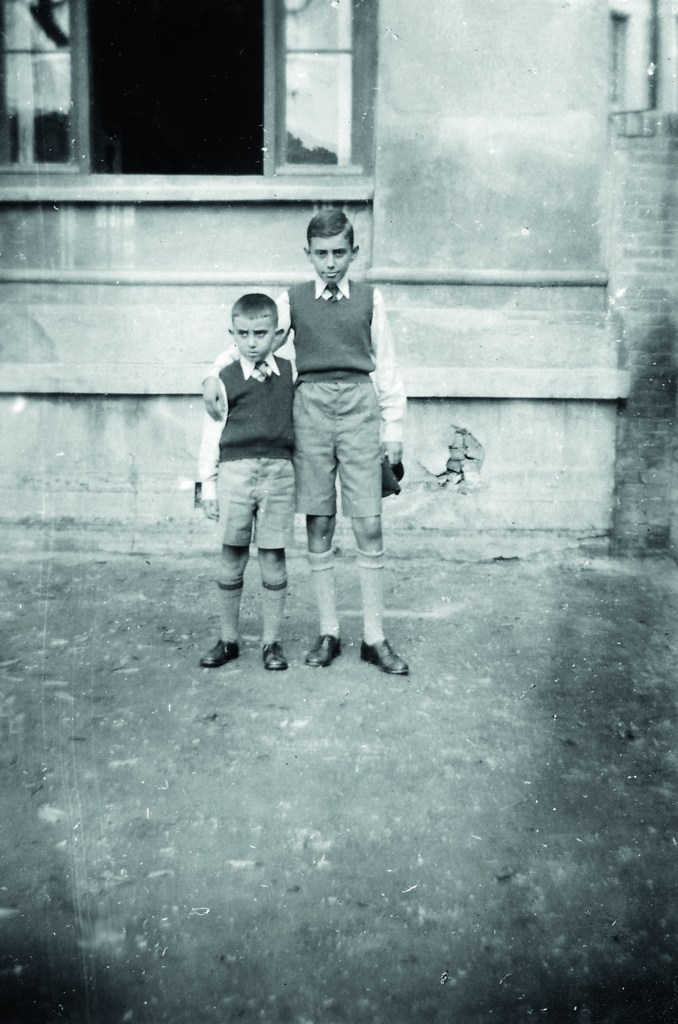

Triguboff attended a Jewish school, spoke a little Chinese and learned to write Chinese script. “The ancient one, the hard one,” he says. After the war, with Mao’s Communist forces advancing, Moshe struggled to liquidate the considerable assets he’d accumulated. Unable to get a visa himself, he sent his two sons to Sydney – the oldest, Joseph, to study law at the University of Sydney, and Harry, 14, to start fourth form (Year 10) at the exclusive Scots College.

Asked what he noticed upon arrival in the southern, sunny land, Triguboff sites the physical landscape. “The people lived in cottages instead of apartments. People had lovely gardens. Thousands of people were on Bondi Beach. No Chinese. All white, but brown.”

Triguboff’s friend Alex Abulafia recalls Triguboff telling him how, when he left his parents, he couldn’t cry. “He was just so excited about the future,” says Abulafia. “He looks forward to what’s next. There’s always a new day. He’s like a kid with his enthusiasm.”

Related

Triguboff says he would never have boarded at Scots. “I didn’t like the food.” Did he taste it? “I smelt it. Dripping!” He stayed with a kosher butcher in nearby Dover Heights. “Now that was good food.” His English was as good then as it is now, he says, with a hearty laugh, and the children of the state’s upper echelons were not unkind to this swarthy kid from the exotic East. “I was friends with the ones who wanted to be my friends … I still meet them now.”

Scots was an enthusiastic rugby school, but he greets a question about whether he played the game with an expression of horror. “Don’t be silly. They suggested I do, but I saw those guys… ” He motions with his arms wide. “…I said, ‘No, no, no. I’ll write history essays instead. I was reasonably big then. Now I’m old, so I’m getting smaller. When you get to my age, you go down.”

His parents were trying to join the boys in Australia, but battling suspicions of collaboration with the Japanese, they were unable to get visas. By the time Harry finished school, they’d found refuge in the new state of Israel, and Moshe had started a textiles factory there. Harry saw his future with his father and so went to study textiles at the University of Leeds in the UK before moving to Israel himself in the mid-1950s.

It didn’t work out. “We had a problem in the family, see. We all loved each other very much. Very big friends. But my brother never really absorbed Israel. He lived there for three years, four years and couldn’t speak Hebrew. Israel didn’t suit him.

“I thought I would go and do a bit of real estate. I sold a bit here and there. I wasn’t much of a salesman, but I knew value.”

“I thought that I know everything, and that was a very bad thing because father was my big hero, and suddenly, when I finish university, I know everything. We used to argue about what to do. So the mother had enough of this bullshit, and she said to my brother and I that we were in Australia before, so we should go back. She sent us both back.”

Harry spent a year working in textiles in South Africa before coming again to Australia, still in textiles. “I was completely confident, but I didn’t know what to do. The textile industry here was dying. I thought it was dying then. It died later, but I saw it then. Our wages are high, our machinery is rubbish, and they produce textiles in China for a fraction of the price.

“I thought I would go and do a bit of real estate. I sold a bit here and there. I wasn’t much of a salesman, but I knew value. If a guy came, I would know what he could afford. So I wouldn’t waste time – I had no patience. A poor woman comes here, it’s the biggest decision she has to make in her life, and I have to listen to all that crap. That’s not me. That’s my fault, not hers.”

When the builder is drunk

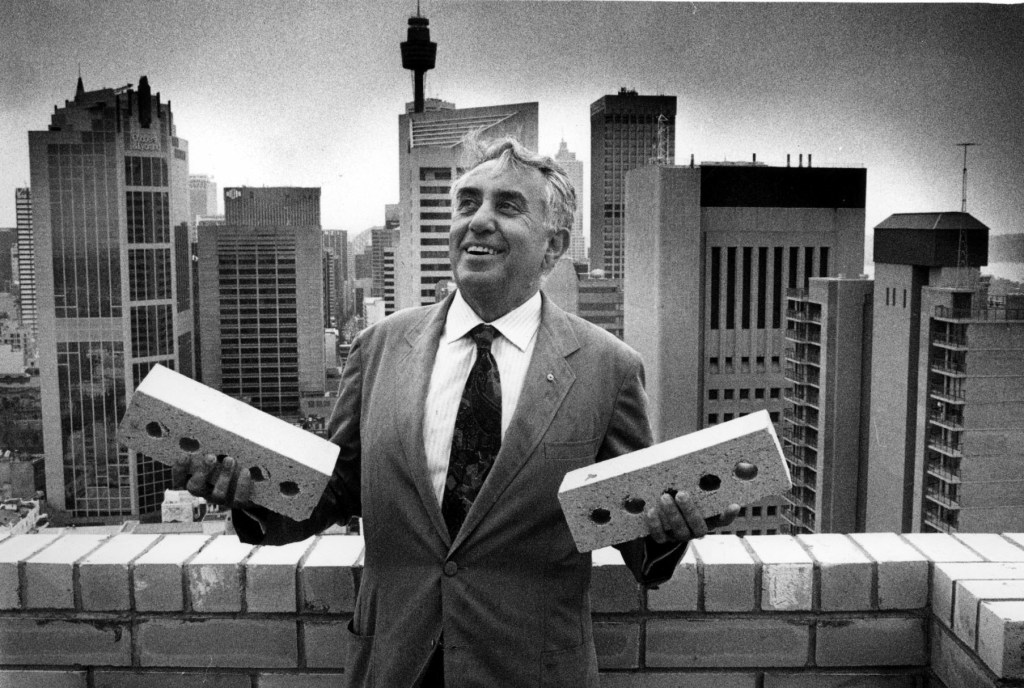

He took a job as a university lecturer. “But I wasn’t much good at that either. I’m not an academic. I had a friend [Thomas Gluck]. He said we should build apartments.” They bought a block of land in the inner southern Sydney suburb of Tempe for £3400.

“I found a builder, but he was a drunk.” With the block half-built, he sacked the builder and replaced him with the bricklayer, Ken McDonald. “He stayed with me 40 years. His children are still with me and his grandchildren.”

The Tempe units sold for £25,500. So Triguboff built another block. But he had bigger plans, and McDonald, still laying bricks, couldn’t be on more than one site at a time. “I realised that a sub-contractor has knowledge of economy. So, the guy with the tiles and the guy with the timber, they should also understand money. So I took every one of my sub-contractors and said, ‘You will build this block. You will build that block, and you will build this block.’ And they all understood money. That’s the important part. That’s how I grew.”

It’s not that he was entrusting his fate to their hands. “I was on the job every day. Every day. I used to also make sure they got supplies. I sourced all the bricks, cement.”

Was he ever on tools himself?

“Don’t be silly,” he says with a look similar to when asked if he’d ever played rugby. “If you can give them constant work, it’s very important. What they don’t like is to finish a job and then go look for another job. With me, they came, and they stayed. Ken’s family, now third generation.”

It’s often mentioned by those familiar with Meriton’s business model that the sub-contractors are kept in work, get invited to his birthday parties, hobnobbing with prime ministers and celebrities, and give loyalty in return. “And you overpay them. But you overwork them too,” he guffaws an uproarious, guttural Russian laugh.

It’s more important to be on good terms with the contractors than the prime minister, he says. “One hundred times more important. Because he has to deliver the job and the people. The prime minister can’t.”

By 1969, Triguboff was big enough to float his company on the Sydney Stock Exchange, with Meriton Properties Ltd taking its name from a Gladesville street where he’d just completed his largest development – 18 units. After a few years of an acrimonious relationship with the exchange, Triguboff bought back all Meriton stock in 1973 and he’s held 100% ever since.

Triguboff Timeline

- 1933 March 3, born in Darien, China (now Dalian), the son of Russian Jewish parents Moshe and Frida.

- 1937 Is in Tianjin, China, when the Japanese invade.

- 1948 Harry, 14, arrives in Sydney from China to attend Scots College while brother Joseph starts a law degree at Sydney Uni.

- 1949 Moshe and Frida get to Israel, the only country that will take them.

- 1951 Studies textile engineering at the University of Leeds, UK.

- 1950s Moves to Israel to work in his father’s textile factory.

- 1959 Leaves Israel for South Africa, then back to Sydney.

- 1963 Builds first apartment block – 8 units – in Tempe, Sydney.

- 1968 Undertakes his largest development to date; 18 apartments in Meriton Street, Gladesville. It succeeds, and he names his company after the street.

- 1969 Meriton floats on the Sydney Stock Exchange.

- 1973 After a volatile relationship with the exchange, Triguboff buys Meriton back at $3.00 a share – $0.70 above the listed value.

- 1974 Difficulties in selling units means he starts renting them out.

- 1979 The sales team shrinks from 18 to one.

- 1980 Marries second wife, Rhonda, having divorced first wife Hana.

- 1984 Meriton expands into Queensland starting in Surfers Paradise.

- 1989 Opens Property Finance division, lending buyers up to 90% of the purchase price.

- 1990 Launches Property Management division, guaranteeing tenants for investors.

- 2003 Meriton Serviced Apartments debuts with 20 serviced apartments in Bondi Junction.

- 2004 World Tower opens. At 84 storeys and 230m, it is Australia’s then tallest residential building.

- 2008 Receives an honorary doctorate from the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

- 2009 Launches Strata Management division.

- 2010 Launches Resales division, a real estate agency for on-selling apartments.

- 2012 Opens 68-storey Soleil in Brisbane. The city’s tallest residential tower at 243m.

- 2013 Meriton’s Infinity passes Soleil as Queensland’s tallest at 81 levels, 262m.

- 2017 Meriton Serviced Apartments rebranded Meriton Suites.

- 2019 Buys first land in Melbourne CBD for $29 million.

- 2019 Buys his first block in Canberra CBD to build serviced apartments.

- 2022 Rebrands the 4,860-strong rental-unit portfolio as Meriton Build for Rent.

- 2023 Opens first Meriton Suites property outside NSW or Queensland, with a 57-storey building on King St, Melbourne.

Why Harry?

Triguboff faced an existential threat in 1974 when an American lender got into trouble, he says, and demanded all loans be repaid immediately. “That bastard comes to me, and he tells me I’m broke. I said, ‘Yesterday you couldn’t give me enough money. Today, I’m broke! I promise you that I’m not broke and piss off.’ I had these half-finished buildings. I said, ‘You’re so fucking smart, you go finish them.’ ‘Ooh, not fair, not fair.’

“So, I said, ‘Sit down, and I’ll finish the blocks, and I’ll pay you off, but don’t tell me payment on demand. And I changed all the bloody mortgage [laws] in this country – that there is No. Payment. On. Demand.” He slaps the table with each word.

“I had these half-finished buildings. I said, ‘You’re so fucking smart, you go finish them.’”

Triguboff wasn’t the only developer throwing up red and cream brick boxes in the 1970s and 80s. Why did he get so much bigger? “Because I’m different.”

In what way?

“If I look at something and it doesn’t make sense, I go and change it. And if the council is stupid, I take them on. You think I yell? I don’t yell much at them ’cause I don’t have time for them. I wish I could. But many people that work in councils are very good friends of mine. They’re happy to work with my organisation because we know what we’re doing. These other poor bastards [developers] come there half illiterate, half crooked. It’s a big advantage to work with me. I’m literate, and I’m not crooked.”

He surpassed his rivals, he says, because his ambitions were more modest than theirs. “They want to grow too fast. My blocks were very small. Others were building bigger ones. Then I caught up. Then I left them behind. I just grew naturally, you understand. Made another $10,000, another $20,000, another $100,000, a million, $10 million. I had more money, so I grew.”

Along the way came some key insights. In 1974, he couldn’t get a satisfactory price for some units, so he held onto them and created another income stream long before the term “build to rent” came into use. Around the turn of the century, he saw that hotel rooms seemed mostly designed for two people and didn’t work for families or long-term visitors who needed a kitchen, so, in 2003, he started building serviced apartments [now Meriton Suites] but with residential approvals in place so that if the market turned, they could be sold as strata units.

It diversified the cash flow, and by the early part of this century, he’d largely freed himself from the banks. When the global financial crisis hit in 2007, he was in a better position than most. He kept building and kept his people in work. When the market rebounded after 2009, he had the team and the stock ready. In 2005, Forbes estimated his fortune at US$1.3 billion. Five years later, after the biggest squeeze in a generation, it had grown to US$3 billion.

Tyrant or charmer?

Property developers were banned from making political donations in NSW in 2009. But it hasn’t stopped those opposing development accusing them of still having sway in the political realm.

Among the 12,800 signatures on the Save Little Bay petition opposed to a recent Meriton rezoning proposal was that of former NSW premier and Maroubra local Bob Carr. Carr says he opposed the development because of its scale. Carr says Triguboff never came across as the bully he’s often portrayed as in their many personal encounters. “He’s great. He’s got a mischievous sense of humour. He’s got no pretensions. He doesn’t behave like a swaggering billionaire might.”

Triguboff once told an interviewer that Carr had told him he “saw me more than he saw cabinet ministers. That doesn’t mean he did what I told him, but he knew [my] story very well.”

Carr says he had no idea if Triguboff donated to his Labor Party when he was in office. “I dealt with him and his company because they were major investors in the state and deserved to be listened to.”

In 2016, when there were fears that too many apartments were being built and rents might fall, Triguboff told an interviewer, “Then I will bring in more migrants.” On the other hand, Carr, the state’s longest-serving premier, had put up a metaphorical “Sydney is full” sign. “Harry and I had some good-natured fun when I was premier. I argued Australia shouldn’t rely on force-fed population growth as the basis of economic strategy. Harry, by contrast, loves high immigration. But any government has got to make sure that he keeps building because you don’t solve housing crises without the private sector making a profit from building affordable apartments.”

Tom Forrest saw Triguboff operate when he was chief of staff to Sydney Lord Mayor Frank Sartor in the 90s, then later to Carr’s successor, the more development-friendly Morris Iemma. Forrest, now head of the property developers’ peak body, Urban Taskforce, says not all government people got the charm that Carr received.

“People go, how does he get away with what he gets away with; with his – how do I put it politely – dominant personality style?” says Forrest. “But the reason he gets away with some fairly hostile conversations and confrontations is that he’s two things. He’s incredibly charming and he’s incredibly loyal to his workforce and his contractors. When other companies are having highs and lows and letting their workers go and then bringing them back on, he feels an obligation to ensure that his pipeline continues to keep his contractors engaged. Harry’s always relied on good people who are 100% loyal. Despite the fact he comes across as a tyrant sometimes, if you get past the first week, then often you’ll stay 20 years.”

Forrest adds a third reason for Triguboff “getting away with it”: that he’s usually right. He cites the example of how, when the 1990-91 recession had left an enormous hole in the Sydney CBD, Triguboff had come in with a plan to make viable the abandoned remnants of a planned four-tower office complex called World Square. “Frank Sartor, the lord mayor, allowed for there to be an amendment to the zoning from ‘commercial-only’ to allow ‘mixed-use’ development, which enabled Harry to build World Tower, which was serviced apartments, a hotel and private dwellings. That helped make the other towers more feasible.

“That’s what Harry’s done all his working life, saying: ‘This will only work if you allow me to do this.’” Sometimes, politicians agree and give him what he wants. Sometimes they don’t. But more often than not, his analysis of what’s wrong is 100% correct. You don’t go from nothing to $25 billion without being fundamentally correct most of the time.”

Schmucks and crying babies

Australia is in the grip of a housing crisis, with capital city rental vacancy rates of 1%. A federal/state agreement, the National Housing Accord, has set a target of 240,000 new homes a year, Australia-wide, of which NSW is aiming for 76,000. “We’ve had 42,000 approvals in the last 12 months. How do you build 76,000 homes if you’ve got 42,000 approvals?” asks Forrest.

So there is pressure on councils and planning authorities to allow denser development, which would suit Meriton mightily. However, because Meriton owns 5,400 rental apartments, it also profits mightily from a chronic housing shortage.

“These dumb politicians, they think they’re punishing me by not allowing more supply. All they’re doing is making me richer.”

“I sometimes wish Harry wouldn’t say that quite so assertively,” says Forrest. “But it’s absolutely true. He’s a winner if they don’t provide more supply because it pushes up the value of the properties he’s banked.”

Forrest adopts a Russian accent: “These dumb politicians, they think they’re punishing me by not allowing more supply. All they’re doing is making me richer. The reason I came number three in Australia is because of them. I’ll take them to the High Court, and they’ll roll over like crying babies. And then, because of their silly restrictions on everyone else, the value of all my property goes up. They’re idiots. Schmucks.”

Former Randwick mayor Dylan Parker, who opposed the huge Meriton proposal at Sydney’s Little Bay, says he has never seen a developer so unwilling to compromise as Triguboff. “I’ve observed it as a willingness to play the long game and to push for the maximum possible amount, no matter what. And if that means waiting– ‘We’re going to landbank until it makes sense’– they do that. It is quite exceptional – they engage in a level of public attacks on decision-makers few other developers would either find acceptable or dare to do.”

A former staffer to a senior politician says that when he met Triguboff, he was surprised at how well he fitted the stereotype of a “boisterous billionaire”.

“He’s essentially banging the table, saying the government won’t get one additional unit from him, whether it was an affordable housing contribution or whatever, not one more unit. I mean, how many does he have? It left an impression on me as someone who fixated on every minute

detail, with an attitude that government is something to be bullied and pushed around rather than worked with, negotiated with.”

“I don’t compromise when I am sure that I am right.”

Triguboff denies he never bends. “I don’t compromise when I am sure that I am right. The problem with councils is their rules. They stick to the rules, and if I come to him and say, ‘Listen, this rule is stupid.’ He agrees with me but says, ‘I can’t change it, or I won’t get my seat.’ It’s not very difficult to beat him up [in court] because when I come to the judge, what I say makes sense.”

No other developer fights like he does, he says, because they are undercapitalised. The banks have a stopwatch ticking. “He has no time. He has no money. He has to be fast. I build with as much money as I have – no more. I have time. They know that what I say makes sense. I don’t just argue because I want something. I tell them this is silly. Lately they didn’t allow a garage for every two-bedroom unit. A cottage has two garages, a unit no garages. It doesn’t make sense. I fought one [council], and I beat them up on that.”

When it is suggested that such a rule might make more sense in a CBD than in the suburbs, he rises: “No, it doesn’t make any bloody sense. Very simple. You’re a philosopher now? I put the units on the market with a garage and without a garage. They [buyers] want the one with the garage. What the fuck do I care what you think? He buys, not you.” Suddenly calm again: “And that’s the answer.”

Sydney lord mayor Clover Moore – who has long opposed residential parking spaces in the CBD, says Triguboff – has been working well with the council. “As lord mayor, I’ve seen many architects and developers work in our city, but none quite like Harry,” she said in a statement.

“We have not always seen eye-to-eye, but I credit Harry for now working with our Design Excellence requirements to achieve some great developments in the City of Sydney.”

Sunday walks

Businessman and community leader Alex Abulafia first met Triguboff while trying to raise money for the Emanuel School around 2005. Triguboff gave $500,000, and they stayed in touch, with Abulafia keeping the billionaire updated on the Jewish community’s goings-on. “He then asked me to go walking with him on Sunday in a little group with his old mates,” says Abulafia. “They’re all octogenarians or nonagenarians now. A lot have died off over the years.”

Abulafia, 63, declines to say where they go. “We start with coffee and a muffin, and then we have, needless to say, a short walk.” They chat about all manner of subjects. “He lets other people talk. He doesn’t need to be the centre of attention. He’s secure in himself. We talk about politics, the economy, about Israel, about his developments.

“People don’t see that side of him. He likes to joke, and he likes to laugh. He doesn’t take himself seriously. He enjoys people. He’s got no airs and graces. He’s not a snob. But he’s very refined.

“I remember once at the end of COVID when you could start having people over, I said to my wife, ‘What are we doing tonight?’ ‘Nothing.’ “I’ll ring Harry. See if he wants to come over for dinner.’ She said, ‘You forget yourself. You can’t just ring him. He’s a billionaire.’ ‘If he doesn’t want to come, he won’t come,’ I said.”

Abulafia rang, and the billionaire said he’d love to come over for a steak. The one trouble was there was a West Tigers NRL game on. “He loves football even though his team never wins. He came over and watched the Tigers game with my son while we ate dinner. That’s what encapsulates Harry to me – a down-to-earth person. He’s passionate about things. Obviously, he’s extraordinarily bright. If you’re talking about things, you need to do it in nanoseconds to keep his attention. But he is so incisive and knows everything. He cares. I remember once I asked him, ‘What’s it like to be a billionaire? I can’t imagine it.’ ‘It’s no different,’ he said. ‘You’ve got to be a good person and not a snob.’ And he is.”

‘That is my greatest moment’

Asked what the biggest moment of his career was, Triguboff cites the early days of the COVID-19 pandemic. “When the virus came, every one of the workers turned up to work. Nobody asked to stay at home one hour. I never asked. They knew the company needed workers.” He’s slapping the table again. “That is my greatest moment. Because they feel like I do. They have to make sure the company survives, and that’s why I’m successful.”

What’s the best deal he ever made? “I made lots of good deals. In principle, the good deals are the big ones, where I buy a big block of land because nobody else can afford it,” he chuckles. “I have no competition, and the poor seller can’t sell it to anyone else. And if I have patience, the council approves it.”

So why doesn’t he just sail off on a superyacht?

“At 90 years old? I’ll get the women there and what will I do? Nothing! What do you want me to do there? Tour? I missed my chance. I should have done it 50 years ago! If they tell you they enjoy it at 90 on a yacht, I laugh at them. I can take it for lunch. That’s all.”

The office is where he gets his thrills. “Work gives me all the time problems and I have to overcome the problems. I have a lot of people, obviously. We overcome together, but I play an important part. And that’s what I like – the thrill of overcoming the problem.”

A melancholy tone comes over his voice as he talks of his generation fading away. “Of course I am sad. I liked them. What can I do?”

His daughters Orna Triguboff and Sharon Hendler, who never went into the business, will inherit it, but three of his grandchildren are working in Meriton and are being prepared to run it. “I have a grandson. He’s very good. Daniel [Hendler]. I have another grandson [Ariel Hendler]. He’s good too, but a different boy. Then I have a granddaughter – she’s also very good too.” They take home the sheets now as well.

How long can he last?

“I told you. Depends on the doctors. Very good doctors.”

Big fish in a Little Bay

When Olde Lorenzen bought a new apartment at Little Bay, a southern Sydney beach suburb, in 2019, he thought he was buying into a low-rise development, a coastal community, even – that would eventually comprise 450 units.

Six months later, after half the site had been completed, Meriton edged out Chinese giant Country Garden in 2020 to buy the remainder of the site for $245 million. And then it dropped a bomb on Lorenzen’s world: it wanted to put another 1,800 units on the land that had approval for just 224 apartments.

Lorenzen was suddenly facing the prospect of a decade of construction over the road as it rose 18 storeys and shaded his dream.

He describes it as terrifying. “When you do all your due diligence as someone who buys an apartment in a master plan, you shouldn’t be confronted with a new plan that’s 850% more than promised.”

Lorenzen began the Save Little Bay campaign, attempting to do what few have done before, beat Harry Triguboff. He knew he was up against a formidable opponent.

The then Randwick mayor, Dylan Parker, under whose jurisdiction the development fell, says the scale of Meriton’s plan was too “over the top” to support. “But what I found interesting is just a unwillingness to come up with an alternative proposal that decision-makers could actually vote for.”

Parker was riled by perceived misrepresentations in the media of the council’s speed of development approvals during COVID-19. “When council pushed back on that with Meriton’s media office, Triguboff’s the one who’s ringing media back. That is quite remarkable a willingness to get involved in the cut and thrust of a political process.”

Nevertheless, the development has now gone before three planning authorities and failed each time, two under the coalition state government and last July, under Labor.

The landscaping, the lake, the playground, and the streetscape have been growing weeds for years behind a Meriton fence.

“It’s a massive, failed investment,” says Lorenzen. “Looking at the planning controls, he would have paid one million per approved dwelling.”

Asked about it, Triguboff is nonchalant. “I am still patient. So far, no success,” he laughs. “No success at all,” he laughs louder. “Doesn’t matter.”

How long can he wait? “Forever! They need it more than I do.”

On why we’re in a housing crisis

“Our big problem today is the banks, not the councils. But whatever I say about the banks nobody ever prints. Probably you won’t either. They are very bad, I’m telling you. Not to me, I don’t borrow. See, a guy wants to buy a unit, so they say, ‘How much do you earn?’ ‘$1000.’ They say you can’t afford it.

“I say, if the unit is worth more than what the bank gives, whatever he earns is not important because, if necessary, he’ll sell it or they’ll sell it. You have to try to help them. They don’t help them. “And they have the idea [developers] have to pre-sell. How the hell can you pre-sell? Prices are going up. I sell you the unit for $1 million. By the time it’s finished, it cost $1.2 million. I can’t get the $200,000 from you. I signed for $1 million. If I didn’t get you to sign for $1 million, the bank wouldn’t give me the money. That’s bullshit, and he knows it’s bullshit, and that’s why nothing is being built.

“They tell you that we don’t have enough workers. That’s crap. People can’t make a profit.”

Triguboff says he’s largely stopped buying land in Sydney. “I am building more than 2,000 a year and could build 4,000,” he told News.com. “Councils fabricate problems for which I would gladly take them to court, but our present rules don’t allow me to do so. And the planning department is not at all helpful. I have almost stopped buying in Sydney and am just using up my empty land.”