Anduril, the company that opened a submarine factory in Sydney today, sits somewhere between a sovereign capability saviour and a sci-fi character.

Anduril’s Asia Pacific CEO David Goodrich asked his board to start building a submarine factory in Sydney 18 months before any contract was signed. “I had a lot of sleepless nights,” he says over an enormous conference table in Los Angeles stamped with Anduril’s axe-head logo.

It was a decision borne less of certainty than a need to get things done.

The autonomous submarine factory that opened in Sydney today is just a small part of Anduril’s massive ambitions to entwine artificial intelligence into every aspect of the battlefield, from a soldier’s helmet to the satellites above.

Goodrich swears he had no prior knowledge of where defence would land in awarding the $1.7 billion contract to build an unstated number of bus-sized autonomous submarines. “We had to build it. Otherwise there was no way we could get into full production in the time we said we would.”

So now, just 51 days after the announcement, the 7,400m² factory is up and running and the first Ghost Shark Extra Large Autonomous Underwater Vehicle (XL-AUV) has rolled off the line ahead of planned delivery to the Royal Australian Navy in January 2026.

It’s the move-fast mentality that has seen Anduril go from start-up to junior defence prime in just eight years, valued at US$32 billion.

And for anybody who thinks it strange that a submarine factory could spring up next to a suburban Bunnings, Anduril CEO Brian Schimpf says Tesla CEO Elon Musk is partly to blame – changing people’s notions of what can be built, and where.

“If you end up building unfettered, super-powerful technology with no thought for the safety … you should be in jail.”

Anduril CEO and co-founder Brian Schimpf

“People are always like, ‘Are you doing too many things?’ But it’s a pretty simple formula. We’re not scaling one 6,000-person company. We’re scaling a lot of 300-to 500-person companies.

“You get people space to run and just let them go.”

Lattice not Skynet

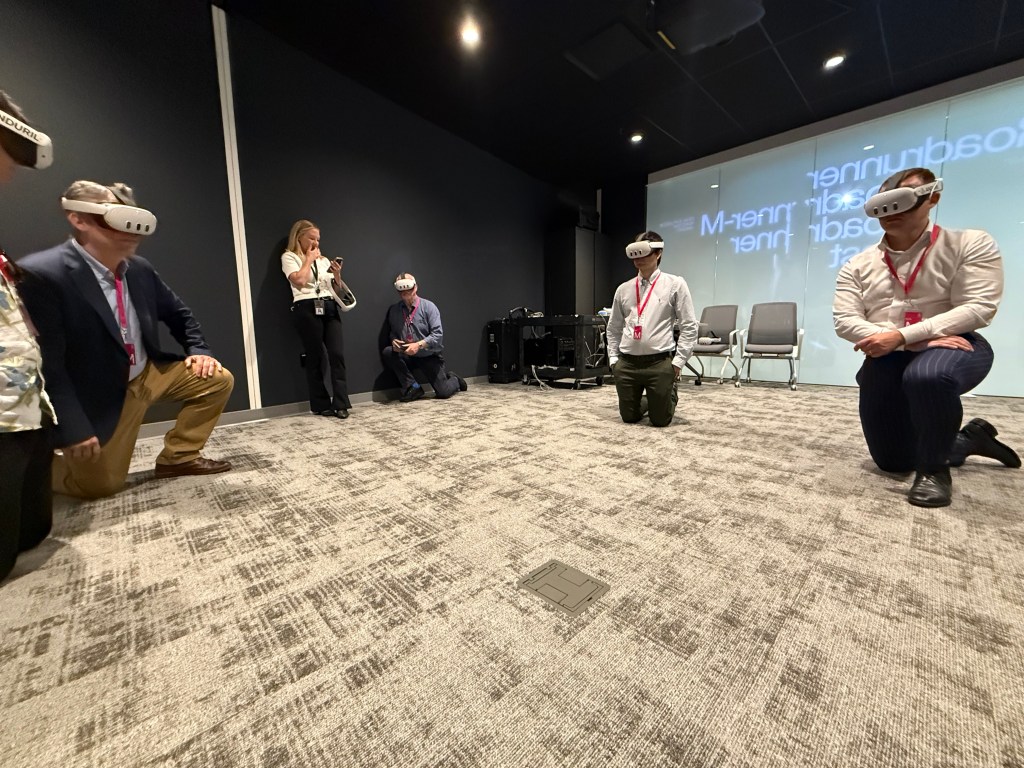

With VR headsets on, the drab room at Anduril HQ in Costa Mesa, California, is transformed into a 3D “sand table” – think World War II movies where they’re pushing planes and ships around big table maps. But this one is brought to life like a virtual reality game.

We’ve been transported to the Baltic, specifically Kaliningrad Oblast, the Russian exclave a quarter the size of Tasmania, carved out by the Soviets between Lithuanian, Poland and the Baltic Sea, and long seen as a possible focus of Russian territorial intent.

We can walk over a green patchwork of paddocks and see the purple footprint of satellites and observational drones above, connected by green lines to each other and down to some F-35 fighters coming in, preceded by unmanned aerial vehicles, a wolf pack of small drones talking to themselves off to the side, hooked up to observation towers connected to tanks and troops, forming a green web of lethality.

We see the enemy forces moving in real time and when the sand table switches to war gaming mode, we see little explosions as the AI plays out scenarios.

The web of green lines between assets represent Anduril’s “AI brain”, called Lattice, designed to co-ordinate multiple defence assets in a web of interoperability, so that if one piece gets taken out, there are other ways for everything to continue talking between themselves and to the wider system.

Our guide in the Sand Table is telling us that the drone wolf pack is “not necessarily” being controlled by humans. “They are enabled through machine learning to understand what’s happening around them and to take actions on their own.”

As are all the elements. We are invited to take a knee and suddenly we’ve gone from 20,000 feet to a 1,000-foot view and the minutiae of the battlefield. “It’s very difficult for the human brain to understand this problem that modern militaries are wrestling with: How do we manage all these assets and defeating masses of traditional military formations with new capabilities like unmanned robotically controlled vehicles.”

The sand table can also go into action mode, depicting a real unfolding battle.

It is telling that Anduril’s first acquisition, in 2019, was Carbon Games whose gaming engine became this visual foundation of Lattice.

“All the other gaming engines had associations with China,” says Allen Ringel, Anduril’s vice president of software platforms who joined the company from Cognizant early this year. “But Palmer could see that for something like Lattice to work you needed to be able to do what gamers do.

“There wouldn’t be too many defence companies thinking about buying a gaming engine as their first acquisition.”

But I can’t help thinking about sci-fi doom scenarios.

Does CEO Brian Schimpf ever wake in a cold sweat wondering if he is creating the real-life equivalent of Terminator 2’s Skynet which takes over the world in an AI apocalypse?

To be sure, Anduril’s Lattice system bears more than a passing resemblance to Skynet in the way it is seeking to integrate every input across a battlefield, from satellites above to an infantryman’s VR headset on the ground.

“No,” says Schimpf, who, like any good tech founder, needs no explanation of the pop-culture reference. In fact, he reminds Forbes Australia that the company that built Skynet was called Cyberdyne. And after umming and ahhing through a few sentences about not becoming Cyberdyne, says he is bothered by the broader AI community.

“They say AI has all these safety risks, and you’re like, ‘Well, what are you doing about it?’ And they’re like, ‘I don’t know what can be done.’ And you’re like, ‘Well, that’s not an acceptable answer.’

“Our view with that is we don’t start with stuff where we’re like, ‘This could be catastrophic for the world, and we’re not going to do anything about it.’ That’s an insane starting position we would never take.

“We’re only going to do things that can be responsibly executed. So that doesn’t put you down the Terminator path. We’re not saying, like, ‘Let’s hook up the super-intelligent AI as soon as it’s available and give it all the keys to the weapons.’ That’s a crazy position.”

“My mission has long been to turn warfighters into technomancers, and the products we are building with Meta do just that,”

Anduril co-founder Palmer Luckey

The guardrails need to be built in from the beginning, he says. “Then what are the safety measures I can put in place to ensure that this mythical super intelligent AI in the future can’t circumvent these policies. Those are achievable engineering problems. This is very solvable in the Event Horizon version of artificial and super-intelligence.

“There’s are all these very pragmatic questions that are quite bland and boring and not exciting Terminator stuff. But that’s where we spend more of our time.

“If you end up building unfettered, super-powerful technology with no thought for the safety … you should be in jail.”

Palmer Luckey, “Professor of Fashion”, is giving a tour of his headquarters’ lobby in Costa Mesa an hours drive south of central Los Angeles. He is apologising not for the Hawaiian shirt and shorts, but for the fact that not every bit of hardware the company makes is on display. There/s not enough room.

There are sentry towers, a seabed sentry, various drones and a sexy scaled down version of an autonomous aircraft called Fury. There’s a torpedo-like thing and part of a bus-sized sub like they’re making in Australia.

Regardless, he cares more for their common denominator, he says. Their “AI brain”, Lattice.

“We have more people working on Lattice than all our hardware systems combined,” he says. “There’s a few reasons for that. One is because there’s just a lot of interesting work to be done on AI capabilities, mission autonomy, but also because in terms of reusability, every dollar I put into Lattice, making that brain smarter, making it better at interpreting sensors, allowing the existing sensors to see further, be more useful, that work generally applies to all my systems.

“So a dollar goes into that, it gets multiplied 30 times across all of our different products.

“We still build good hardware, but it wouldn’t be able to do nearly what it does if it wasn’t for Lattice.”

Luckey had recently returned from a trip to Tawain, into which Anduril has sold multiple products he mostly won’t discuss. But its model of defence has relevance for Australia.

“The problem [for China] is not actually the invasion. It’s that they will then need to have a sustained occupation … where they will have to crush a very tech-savvy, highly intelligent, well-equipped resistance.

“Imagine what Afghanistan would have looked like if Afghanistan was a global tech powerhouse filled with top engineers.”

Unlike Ukraine or Afghanistan, Taiwan won’t be able to import weapons during a fight with China.

“What we’re trying to do is not just build the tools that will allow Taiwan to fight well on day one, you want to build those tools on day 10, day 100, day 1000. That means domestic production. You want to be building things that are so easy to build that they’re building them in little distributed warehouses out in the countryside and then using them to strike Chinese convoys.

“And you want China to know that these things exist .. that we have cruise missile factories that are a dozen people in a shed.”

Asked if he’d toured such facilities in Taiwan’, he says he’s seen “all kinds of things … and China’s gonna have a hell of a time digging out everything that’s everywhere”.

And like the weapons on display in the lobby, showing off this stuff is part of the calculus. “Obviously there’s things you want to keep to yourself, but a lot of it you want to demonstrate … the lower-cost kind of mass-scale systems that Anduril specialises in are the ones that you most want to show off, because you don’t gain anything by hiding the technological capability. The technology is not really what is impressive. It’s the fact that you can manufacture it with this 12-guys-in-a-shed approach.

“Like Barracuda. Every Barracuda cruise missile can be made with 10 simple hand tools, and it’s about 90% fewer parts than competing systems.”

The shortage of exquisite weaponry and ammunition in Ukraine has shown up the shortfalls in much modern military planning. Anduril has tried to build a simplicity into all its manufacturing that Australia could leverage, he said. If it had the will.

“The types of industrial robots and welding machines that can build Ghost Shark are very similar to what you need to build, for example, our cruise missiles and our other technology.

“My belief is that a country can only mass manufacture arms if it designs arms that can be mass manufactured by the industrial base it already has.”

He uses the example of the US in World War II. “We didn’t just say, Hey, look, imagine how cool a plane we could build if we built brand new factories, brand new labour, brand new assembly machines.

“We said: ‘What can you make in an automotive plant?’ It was very specific. How thick of metal can we weld? What gauge of steel can we bend? What radiuses can we actually do using equipment that was designed to manufacture automobiles, industrial equipment, farm equipment?

“That’s what Anduril’s trying to do. We’re trying to build submarines that can be built in car factories. We’re trying to build cruise missiles that can be built in farm implement factories. Because if I need to make 100 times more things, I am not going to be able to do it in any facility that I need to make.

“And I think the same is true in Australia … What if you need to make 10 times more? The Sydney facility is not gonna do it. Luckily we’ve designed it in a way where lots of other reasonable industrial capabilities could be pivoted into doing it.

“The compare and contrast here is the current defence industry. You cannot build F-35s in a Ford F-150 factory. So if you need to build 10 times more, it’s just impossible.”

“Zuck is great”

Of Anduril’s four key founders, two are overt Trump supporters – Luckey and former Palantir employee Trae Stephens – while the other two, Schimpf and Matt Grimm, are declared Democrats. For that reason, Stephens and Luckey do most of the schmoozing with Washington.

For his part, Luckey says Silicon Valley no longer hates him. Not since Russia invaded Ukraine.

And even Mark Zuckerberg, whose swing to the right has been noted by observers, has made up with Luckey so the two can work on putting augmented reality headsets on soldiers in battle, which will see individual combatants hooked up to the Lattice AI brain.

Luckey had famously sold to his virtual reality headset company, Occulus, to Facebook for US$2 billion in 2014 when he was just 21. He worked for Facebook on an eight figure salary before being sacked in 2016, reportedly for his support for then presidential candidate Donald Trump.

Luckey told Fortune that Zuckerberg had apologised to him for his sacking from Facebook [now Meta]. “The people that made that happen are all gone. All of the people—the eight people who orchestrated my ouster—don’t work at Meta.”

Now he’s back working with his old colleagues at what is now called Meta, working on putting AI into soldiers’ helmets. “My mission has long been to turn warfighters into technomancers, [A reference to a 2016 video game] and the products we are building with Meta do just that,” Luckey says on the Anduril website.

The partnership stems from the Soldier Borne Mission Command (SBMC) Next program, a $22 billion program originally awarded to Microsoft in 2018 to develop augmented reality glasses for soldiers.

But the US Army stripped management of the program from Microsoft and awarded it to Anduril, early this year. If Meta wanted in on the action, it had to go through Anduril.

The devices will use Meta’s VR hardware which stems from the headsets Luckey sold them back in 2014.

Asked by Forbes Australia how he was getting on with Zuckerberg, he says they were doing “great”. “I teamed up with Meta so that I could get access to all of my old intellectual property, so we’re doing well. Not talking about Mark specifically, in general Silicon Valley people are mostly okay with the Anduril because Russia has been so brutal in Ukraine.”

But he’s prepared for opinion to switch back. “There’s a decent chance that everyone changes their minds again so I’m ready for a rollercoaster ride over the course of my career.”

The Anduril Rocket ship

- Opened autonomous submarine factory in Sydney on Friday 31, October.

- Raised US$2.5 billion in June 2025, valuing the eight-year-old company at US$30.5 billion.

- Invested about US$80 million to build a high-volume solid rocket motor plant in McHenry/Stone County, Mississippi, now in full production.

- Building Arsenal-1, a hyperscale manufacturing campus in Ohio based on Tesla’s giga factory model, set to open in 2026.

- Taken control of the army program to produce virtual and augmented reality headsets for soldiers in battle after Microsoft failed to produce.

- Founder Palmer Luckey announced a strategic collaboration with Meta to co-develop the Eagle Eye headsets. The US$22 billion contract aims to put AI into soldiers’ helmets with augmented reality goggles.

- Employs almost 7,000 people and will add 4,000 more when Arsenal-1 is fully operational.