Grace Forrest was 18 when she launched the human rights organisation Walk Free. It is at the forefront of the war on modern slavery – which could affect $730 billion worth of G20 imports, according to Walk Free’s estimates. Forrest is aided by start-up FairSupply and its founder, Kim Randle, as they seek to end modern slavery – for good.

This article was featured in Issue 8 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

When Mahendra Pandey turned 18, he left his home, a rural village in Nepal, to find his father, who’d left eight years earlier for a job in Saudi Arabia. Pandey had to pay a steep fee to a recruitment agency to find a job and wait four months for a visa, but eventually, he was on his way.

Minutes after landing, Pandey recalls the company he was sent to work for took his passport to prevent him from leaving the country without their permission. He also realised he wasn’t assigned the job he applied for. The nightmare soon began.

“I faced so many forms of exploitation,” Pandey says from Nepal. “From working 18 hours a day, not being given enough food, being unable to contact my family and sometimes threatened by my supervisors and managers.”

He found his father had faced similar conditions, virtually without pay. “I can’t tell you how heartbreaking it was,” Pandey says. “You know, being a son and seeing your dad and the struggle.” But this is the story of many migrant workers – particularly those in Saudi Arabia, which is one of the top 10 countries in the world when it comes to the prevalence of modern slavery.

Pandey escaped Saudi Arabia 10 years ago by convincing his company to let him return to Nepal for family and health reasons. He never went back. Today, Pandey uses his experience to engage with government leaders for change as the senior manager of forced Labour and Human Trafficking at Humanity United. He’s also the founder of a Nepalese migrant worker network, Shramik Sanjal, that provides pre-departure orientation training and valuable contacts and advice should migrant workers be subject to exploitation.

Pandey is just one of the survivors that Grace Forrest, daughter of Australian billionaires Nicola and Andrew Forrest, works with as the founding director of the human rights organisation Walk Free.

Forrest spoke with this publication a few weeks earlier from London, where she was recently appointed Commissioner for the new Global Commission on Modern Slavery and Human Trafficking, chaired by former UK Prime Minister Theresa May.

The new Commission, crucially, includes the voices of survivors Sophie Otiende and Nasreen Sheikh. Holding Walk Free’s latest Global Slavery Index – a chunky textbook – Forrest says she won’t be part of any organisation that doesn’t champion survivors first.

“It’s just not good enough,” Forrest says. “We can’t rely on the same changemakers in the fields we see. We need people from the communities most impacted and affected because people closest to the issues are also closest to the solutions.”

Forrest was the same age as Pandey when he left for Saudi Arabia when she launched Walk Free. Now 30, she’s been advocating for survivors of modern slavery for more than a decade. Before that, she studied international relations, social justice and political

science at the University of Notre Dame in Western Australia.

“I’ve always been interested in human rights issues,” Forrest says. “I was very much raised with the idea that you do what you can with what you have, and I knew I wanted to work in international human rights, policy and law.”

But the idea to launch Walk Free came to Forrest after working with children who had been rescued from child sex trafficking. After seeing the devastating effects of human trafficking first-hand, she was prompted to look for an organisation to align with.

…There’s a severe lack of transparency in the supply chains of the goods we need for a green transition. You can’t harm people in the name of saving the planet.”

– Grace Forrest, founder, Walk Free

“There wasn’t one,” she says. In 2011, she took it upon herself to start one, launching Walk Free which aims to eradicate modern slavery in our lifetime. Walk Free has published five editions of its Global Slavery Index, the world’s leading data set on modern slavery; engaged with governments, businesses, and faith leaders; and invested in frontline organisations.

According to Walk Free, modern slavery covers a set of specific legal concepts, like forced labour, debt bondage, forced marriage, slavery and slavery-like practices and human trafficking. Essentially, it refers to situations of exploitation that a person cannot refuse or leave because of threats, violence, coercion, deception, and/or abuse of power.

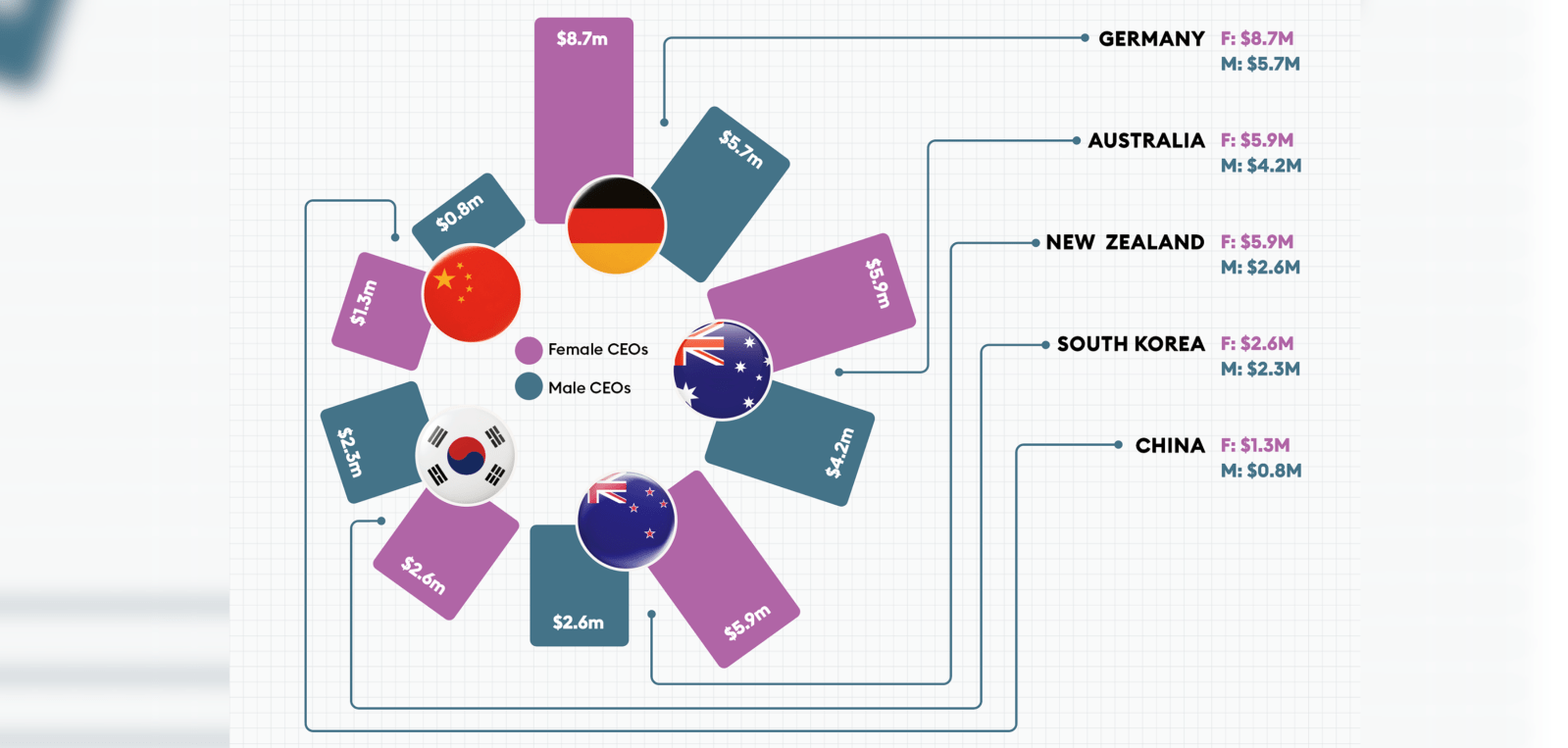

The problem is increasing: the 2023 Global Slavery Index, published in May this year, found more people (50 million) were living in modern slavery in 2021 than in 2018, the last time it was published. Of that 50 million, 28 million were in forced labour, 22 million in forced marriage, and 12 million were children. This marks a 25% increase over the past five years. The research identified that US$468 billion (AU$730 billion) worth of imports from countries that form the G20 could be affected by modern slavery.

“I’ve met and worked with survivor leaders from Australia, the United States, North Korea, Palestine, India. I think what the Global Slavery Index tells us is modern slavery exists in every single country in the world,” Forrest says.

In Australia, about 41,000 people (or 1.6 per 1,000 people) still live in various forms of modern slavery and Walk Free estimates the nation imports US$17.4 billion worth of products at risk of being made with forced labour each year. But, positively, Australia is at the forefront of

action to eradicate it, with the introduction of the Modern Slavery Act in 2018, which came into force in 2019 and is under review in 2023.

“I think modern slavery is, by default, a hidden issue,” Forrest says. “And only since COVID-19 have we been kind of shaken and woken up to the supply chains of where things come from and the implications and living conditions for people at the front of those supply chains.”

To bring modern slavery to light – and the businesses that perpetuate it to account – Forrest works with companies like FairSupply.

“I think that transparency has been viewed as something that is a nice-to-have and not a central component of how we do business,” Forrest says. “And the reality is, if you have forced and exploitative labour in your supply chains, why should you be celebrated as a fair business leader? Our partnership with FairSupply is so important.”

FairSupply, in its first iteration, was founded by ex-commercial-litigator-cum-human-rights-advocate Kim Randle and started operating on the same day the Modern Slavery Act did: 1 January 2019. That was deliberate. In her role as senior director of the International Justice Mission, Randle realised that while Modern Slavery legislation was being driven by academia and NGOs, it would very quickly become a compliance issue for the country’s most sophisticated and luxurious organisations.

“This was the first piece of legislation that required companies to identify modern slavery risks and mitigate them and report them to the government,” Randle says.

From an investment perspective, if a balance sheet is based on labour exploitation, then the whole balance sheet and valuation of the company is wrong. The more regulatory requirements require companies to identify where labour exploitation – it could all come down like the subprime mortgage market.”

– Kim Randle, co-founder, FairSupply

“There wasn’t a commercial solution to the human rights problem in circumstances where it was quickly becoming a commercial issue. I launched FairSupply initially as an incorporated legal practice and assumed I could partner with the technology that maps supply chains and identifies risks, but no technology existed.”

After meeting co-founder Arne Geschke, who had 15 years of global supply chain mapping experience, the pair created a proprietary SaaS product that takes companies’ procurement information, maps their supply chains and quantifies modern slavery risks, carbon emissions and biodiversity impacts, relaunching in October 2019.

The company has analysed more than $750 billion of procurement and investment data for AustralianSuper, Synergy Energy, luxury fashion label AJE, luxury automaker BMW and Lorna Jane (and RM Williams, owned by the Forrest family).

Annett Borg, product and sustainability at Lorna Jane, says that as the fashion industry began to take notice of modern slavery, the activewear company decided to look into its supply chain to ensure the workers making its products were working under safe and fair conditions, enlisting Fair Supply to help.

“We wanted a compliance partner with a human-rights approach, and Kim had the right background and experience,” Borg says. At the time, Lorna Jane had been assured by its supplier that it was meeting living wage standards in its factories but hadn’t conducted its own independent audit to make sure of it.

“FairSupply conducted the audit and confirmed fair compensation at our main factory. We also found that we needed to align paid overtime practices with local standards and discovered minor issues, including missing water test certificates. We then worked on fixing the issues with FairSupply and established a responsible sourcing strategy for our factories.”

But while the fashion industry and its opaque supply chains might be an obvious at-risk industry, agriculture, construction, cleaning, and security are less so. This is because they rely on low-skilled migrant workers.

Even when businesses operate in low-risk industries, like banking or finance, they may inadvertently be contributing to modern slavery by working out of an office building that may have exploited cleaners or security guards.

“Because of the labour and skills shortage in Australia, companies are using labour hire agencies from overseas and employing migrant workers,” Randle says. “So, companies here are very

legitimately employing migrant workers and care deeply about ensuring these workers are paid and treated fairly, but these workers have illegal debts to overseas recruitment agencies. So, all of the money that they’re earning in Australia is going to pay these illegal debts.” Randle says the repercussions of increased modern slavery compliance could be dire – equating it to the subprime mortgage crisis of 2008.

“From an investment perspective, if a balance sheet is based on labour exploitation, then the whole balance sheet and valuation of the company is wrong. The more regulatory requirements require companies to identify where labour exploitation – it could all come down like the subprime mortgage market.”

FairSupply raised seed funding from the Minderoo Foundation, created by the Forrest family in 2001 to drive their philanthropic endeavours, and completed a $6.3 million Series A round in December 2022, again with contributions from Minderoo. The company also received the Invest Tokyo grant in late September and plans to expand internationally in Japan and other markets within the next 12 months to keep up with the regulatory tailwinds in those jurisdictions.

“Think about it like health and safety was 20 years ago when it first came into effect,” Randle says. “I think modern slavery compliance will eventually be BAU.” And Forrest is equally dogged in her commitment to the cause.

I hope that if the next generation goes abroad, they don’t experience trauma like I had to.”

– Mahendra Pandey, survivor and senior manager of forced Labour and Human Trafficking, Humanity United

“While progress is possible, it’s certainly not inevitable,” she says, giving the example that the pandemic rolled back some of the positive change created by Walk Free. Over the next 12 to 18 months, Walk Free remains focused on accountability for the world’s most powerful nations – those in the G20 – particularly as they embark on their clean energy transition.

“I completely support a green transition, but it needs to be a just transition. There needs to be transparency,” she says.

“We know that, from a climate-related disaster, vulnerable populations become more vulnerable to exploitative labour, to distress migration, to various forms of human trafficking. But we also know there’s a severe lack of transparency in the supply chains of the goods we need for a green transition. You can’t harm people in the name of saving the planet.”

Forrest is also steadfast in working with survivors like Pandey to get their stories heard and their hopes realised. Pandey’s is this: “Migrant workers leave for their destination country with health and hope. We come back with trauma. I hope that if the next generation goes abroad, they don’t experience trauma like I had to.”

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.