PHILIP KING co-founded fund management powerhouse Regal in 2004. He is now CIO of the firm, which has offices in Sydney, Singapore and New York, and is recognised as one of the “pioneers of the Australian alternative investment industry”. He explains his surprising outlook for resource stocks, how water became a better investment than land and why the AI sector is currently only a watching brief.

‘Philip King: Where I’m putting the money’ featured in Issue 9 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

What are the fundamentals for you as an investor in this uncertain world?

The most crucial factor driving asset returns over the last 15 years has been interest rates, and that continues. Rising interest rates affect asset valuations and make many assets look more expensive. Earnings have held up a lot better than most people expected.

I’m more focused on long-term rates.

I think it’s long-term rates that drive equity valuations, for example. I know short-term rates get a lot of attention and a lot of press, but I think it’s long-term rates that [are the] drivers.

So, what are you seeing with equity valuations at the moment?

The US market looks expensive at a headline level, but I think there’s lots of value under the surface. We’ve probably had the greatest divergence in individual stock returns for a long time. We’ve seen many stocks do incredibly well, such as the Magnificent Seven [Apple, Alphabet, Microsoft, Amazon, Meta Platforms, Tesla, and Nvidia], but many other stocks are left behind. I think there are great opportunities to pick up many unloved stocks at the moment. And that’s where we are really focusing our portfolios.

Where are those unloved stocks? Where are those opportunities?

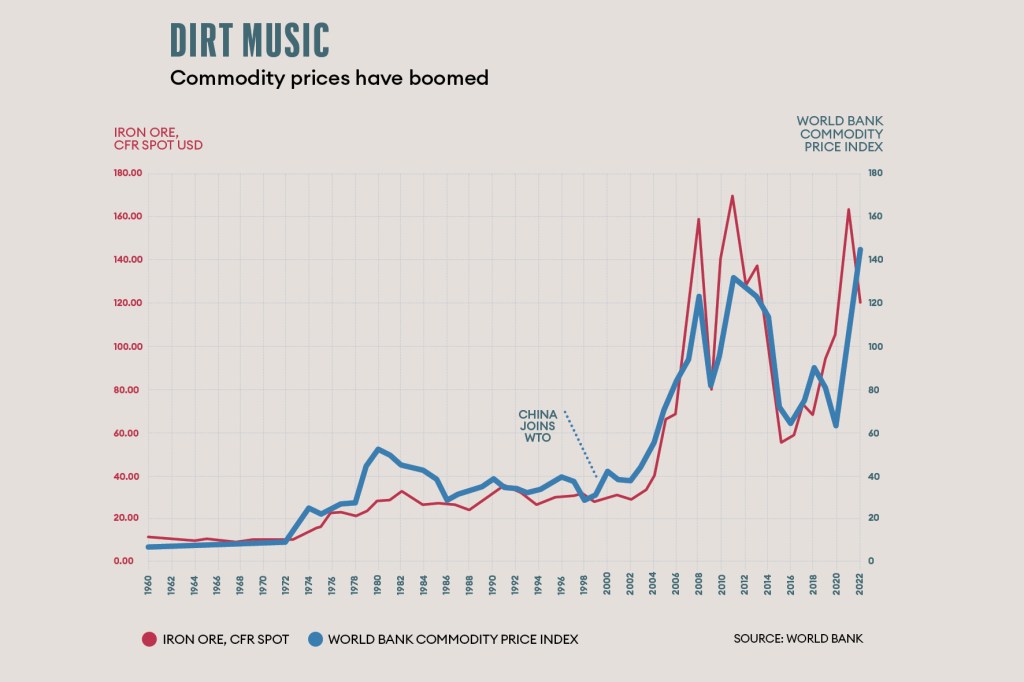

One area that we like at the moment is resources. We think resources are trading at cheaper valuations than historically they have. Part of that is that there are some people selling mining companies because they don’t want to own them. Still, we’re seeing some very powerful factors on both the demand and the supply side that we think will cause commodity prices to increase significantly over the next five to 10 years. Those factors on the supply side are things like that, and it’s getting so hard to get mining approvals in mining-friendly countries like Australia.

The number of new mines that we’re seeing outside one or two commodities like lithium is very, very few. Not only that, but it’s getting harder and harder to find new deposits of economic significance. Even for existing mines, operating costs are going up a lot. So, there’s a lot of supply-side pressure. On the other hand, we’re seeing that some of the factors that work on the demand side, such as de-carbonisation, will mean that demand for things like copper is expected to double over the next 10 years. When these supply constraints and demand increases collide, we think it will have a powerful impact on commodity prices.

It’s a global phenomenon. Even in places like Canada, there’s been a lot more focus on environmental issues, rightly so. But it still makes it harder to get new permits. We’re just not seeing the same amount of discoveries that we’ve seen in previous decades.

So, while this is a supply problem, does it mean equity valuations will look pretty good?

One hundred per cent yes. The lack of new mines means the value of existing mines goes up a lot. We’re very bullish on many copper producers and other miners.

What areas are you avoiding?

Some of the most expensive stocks in the market are some of the loss-making tech companies and some of the high-priced tech companies. One thing that’s happened over the past few years is that many technology companies have gone up a lot, regardless of whether they’re making profits or high-quality companies. So, there are some great technology companies out there, but there are also many companies we’re not sure will make profits. We think that many of the loss-making tech stocks are stocks to avoid.

There’s been an enormous amount of chat about AI. Do you see any opportunities there?

We’re focused mainly on Australia, so there are not many opportunities to benefit from AI [here], but it’s certainly a huge, new area, and it’s just a little bit uncertain how it will all play out. So, at the moment, we’re just really watching things.

What are your thoughts on the current economic climate? What do you see as some of the over-the-horizon threats?

Over the horizon threat is just the impact of rising interest rates on the economy. And the big lesson from the COVID-19 crisis is that the fiscal stimulus we experienced during [that time] has had a much more significant and long-lasting effect on the economy than anyone expected. As a result, we think that the economic slowdown could be deeper and longer lasting than many expect. We’re just wary about [that] when it finally comes. That’s probably our main area of focus at the moment.

So it’s a definite when? It’s not an if?

We certainly think that in Australia, things are slowing, and we believe that economic growth will weaken.

What are the factors that will cause that?

It’s simply a response to the significant increase in interest rates we’ve seen over the past year or two. And that’s flowing through to the economy now. Many consumers are on fixed-rate mortgages. Many of those mortgages have rolled off over the course of [2023], and that’s caused many people to tighten their belts. And that belt-tightening has a multiplier effect through the economy, and so we expect things to weaken from here.

Do you think the RBA and the Fed have got more rate rises to go?

From the recent economic data that we’ve seen in Australia, we may have seen the last of the rate rises [here]. Certainly, I think most people expect the US Fed to cut rates [in 2024].

“We certainly think that in Australia, things are slowing, and we believe that economic growth will weaken.”

Given the geopolitical situation at the moment, how is that going to affect the investment landscape?

The direct implications on the investment landscape are a little bit limited. What’s happening in the Middle East is tragic, but I think the read-through for most Western economies is limited. We’ve seen some de-globalisation in recent years, and I think that’s a fact that will continue as many countries seek to become more self-sufficient in many aspects of their supply chains. Also, we’re going to see increased spending on defence globally going forward. That doesn’t have too much significance for the Australian economy.

Is de-globalisation a good or bad thing?

I think it’s disappointing. Undoubtedly, the world can produce more if we all work together.

What do you see as the future of iron ore and coal?

The iron ore price has surprised most people in the short term because most expected it to weaken due to the weakness in the Chinese property sector. But the iron ore price has been incredibly resilient, and that’s because Chinese steel demand has held up better than anyone expected. And so I think the outlook for iron ore over the medium term is quite positive. But in the longer term, there’s going to be a lot more supply from Africa at some stage.

The outlook for coal needs to be differentiated – we need to talk about thermal coal, which will have a limited life as we have new sources of electricity from renewables and as battery technology improves. But on the other hand, we expect that the demand for [coking] coal will continue to be strong, and, with limited new supply coming on, I think the outlook for [that] is very positive.

China, at the moment, has a stumbling economy. What’s happening, and what does that mean for us?

I think it’s fair to say the Chinese economic miracle is over. They had a couple of decades of amazing growth due to factors like urbanisation, rising property prices and increasing debt levels. But many of those factors have slowed, so Chinese growth going forward will be a lot more muted.

But the good news is that the Chinese economy will continue to rebalance, which will be a good thing for the longer term. Still, I think it’s fortunate that, hopefully, other countries like India can pick up the slack and have a more meaningful impact on global demand.

The important thing to say about China is that even though the percentage growth is much lower than it used to be, the Chinese economy is a lot larger now, so it still has a meaningful impact on global demand.

What about the US?

In the US, it’s a similar story to Australia in some ways that the economy has been a lot more resilient than we expected. Still, we’re finally seeing a little bit of a slowdown occur, and that’s, I think, very positive.

Like many observers, we hope to see a soft landing in the US. We’ll see a slowdown in inflation without causing too much impact on the economy or the jobs market.

Europe?

I think Europe will continue to muddle on, but I don’t think we’ll see the same sort of growth rates from Europe that we see in the US. I don’t see anything on the horizon that will suddenly cause Europe to become higher growth or more efficient.

Are you looking overseas or domestically for investment opportunities?

Some of the best opportunities we see in investment markets are outside traditional asset classes, outside of long-only equities and bonds. We’re investing a lot in newer asset classes like private credit, where we think we can achieve double-digit returns without the volatility of equities. We’re investing in alternative asset classes like resource royalties, which greatly benefit from rising to moderate prices without the drag of higher costs. And we’re investing in alternative asset classes like water, electricity, and carbon, where we think we can generate very good returns in asset classes that are less competitive than equities.

What do you see as the future of the fixed-income market in the short to medium term?

I think the fixed-income outlook is becoming increasingly attractive as interest rates increase. I think it’s becoming much more attractive to invest in.

Where is the Aussie heading?

I think the Aussie dollar is largely trading at these levels due to a very strong US dollar, and we would probably expect the Aussie dollar to trend higher over the next few years, reflecting a slightly softer US dollar and higher commodity prices in Australia.

What should investors be looking for in individual companies?

Investors should look for companies with a real edge and a real moat around their business. So, even though many of the businesses we look at are different from what we looked at 20 or 30 years ago, some of the principles of great investors like Warren Buffett remain very true in that we’re looking to invest in companies that are leaders in their field and have a strong investment moat around their businesses.

Are there any trends you are watching?

We’re just very focused on commodities. We’re very bullish on soft commodities as well as hard commodities. And that’s why we have a farmland fund. And we are also bullish on the outlook for water prices and think water provides a better return than farms [and] farmland. And that’s occurred over the last 10 or 20 years, and we believe it will continue over the next 10 years largely because land in Australia is quite plentiful. The water is the largest constraint in terms of farming. So we think the outlook for water continues to be a lot better than the outlook for land, especially considering that we’ve had a wet few years and many forecasters are predicting an El Niño effect in Australia, which should be very positive for the price of water.

This article represents the views only of the subject and should not be regarded as the provision of advice of any nature from Forbes Australia. The article is intended to provide general information only and does not take into account your individual objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance. You should seek independent financial and tax advice before making any decision based on this information, the views or information expressed in this article.

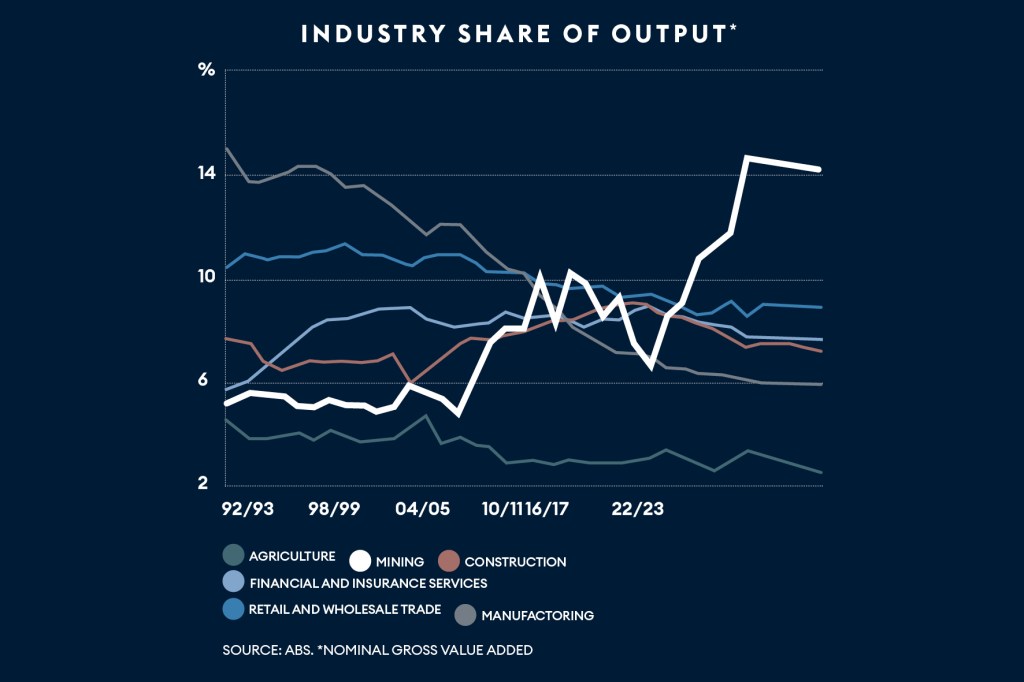

Mining – Australia’s true love

Tracking the history of commodities mining in Australia

Words by James McCreery

Coal – 18th century

First discovered by escaped convicts in 1791, three years after the arrival of the First Fleet.

Commercial mining began shortly; the export industry started in 1799 with shipments to India.

Gold – 19th century

Gold was discovered in Bathurst NSW on February 12, 1851, followed closely by discovery in what would become Victoria – triggering a gold rush.

Australia produced approximately 40% of the world’s gold in the 1850s.

Resources boom – 20th century (1950+)

A slew of discoveries, including modern resources such as bauxite, nickel, tungsten, rutile, uranium, oil and natural gas, combined with the onset of globalization and consequent demand pressures, saw mining solidify its place in Australia’s economy.

A lifting of iron ore export controls preceded the development of the Pilbara iron ore region in WA.

The rise of China – 2000s

2001: China joined the WTO. Australian Iron ore exports to China grew at an average of 23% per year from 1999 to 2011, and mining doubled its share of Australian GDP.

Post pandemic

During the pandemic, iron ore exports were approximately halved.

Mining leads Australia’s pandemic recovery. In 2FY 2023, mining delivered a record $455 billion export revenue.

Future

The bull leaves the China shop; China expected to reach peak steel output last year and has been focusing increasingly on the service sector. According to the Australian Office of the Chief Economist, this could mean iron ore prices softening to US$63 by 2028 and an expectation that China’s iron ore demand will decline by around 1% annually.

Environmental conscience

Mining’s ability to reach ESG (Environment, Social and Governance) goals has become ever more concerning for shareholders and the general public.

Young talent is shifting away from the mining industry. A 2023 McKinsey research paper found that 70% of its 15-30-year-old respondents “definitely wouldn’t” or “probably wouldn’t” consider working in the mining industry. Consequently, a transition to sustainable energy is on the horizon, with demand for initiatives such as green hydrogen, nuclear, wind, and solar power inversely correlating with the desire for iron ore, coal, and LNG.

Critical minerals and technology

Minerals such as beryllium, graphite, lithium, and silicon are registered on Australia’s critical mineral list, which includes minerals essential to modern technologies and national security.

The Federal Government’s Critical Mineral Strategy outlines: “the enormous opportunity to develop the sector and new downstream industries which will support Australia’s economy and global efforts to lower emissions for decades to come”, according to Federal Resources Minister Madeleine King.

The Mineral Council of Australia estimates that 140 new copper mines, 60 new nickel mines, 50 new lithium mines, and 17 new cobalt mines will be needed by 2030 alone.

Investment into ‘new’ resources such as green hydrogen appears promising. In 2022, Australia became the first country to export hydrogen – shipping liquified hydrogen to Japan. Australia also holds 28% of the world’s uranium resources.

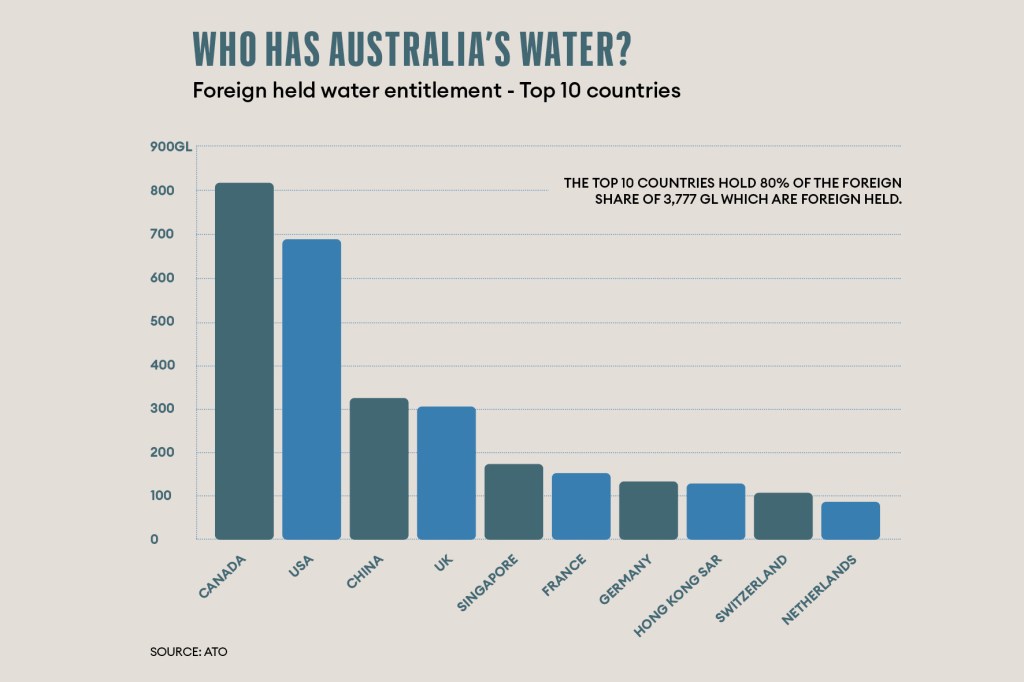

Securing Australia’s water

Water is probably the most precious and unpredictable of Australia’s commodities. And there are numerous competing interests, both domestic and foreign.

Words by James McCreery

MARKET FORCES mediate Australian water use. Users can buy or sell water rights independent of land ownership. This system aims to ensure the efficient use of the country’s scarce water resources.

For example, higher-value crops will more likely receive water more readily because of their remunerative nature and therefore, critical agricultural products should be ensured.

Trade occurs in entitlements (permanent trade) or allocations (temporary trade). Water entitlements are the right to an ongoing share of water, the financial value of which is determined by markets. Allocations are the amount of water distributed to entitlement holders in a given ‘water year’; these allocations vary with rainfall, inflows and amassed water stores.

“Water entitlements are the right to an ongoing share of water, the financial value of which is determined by markets.”

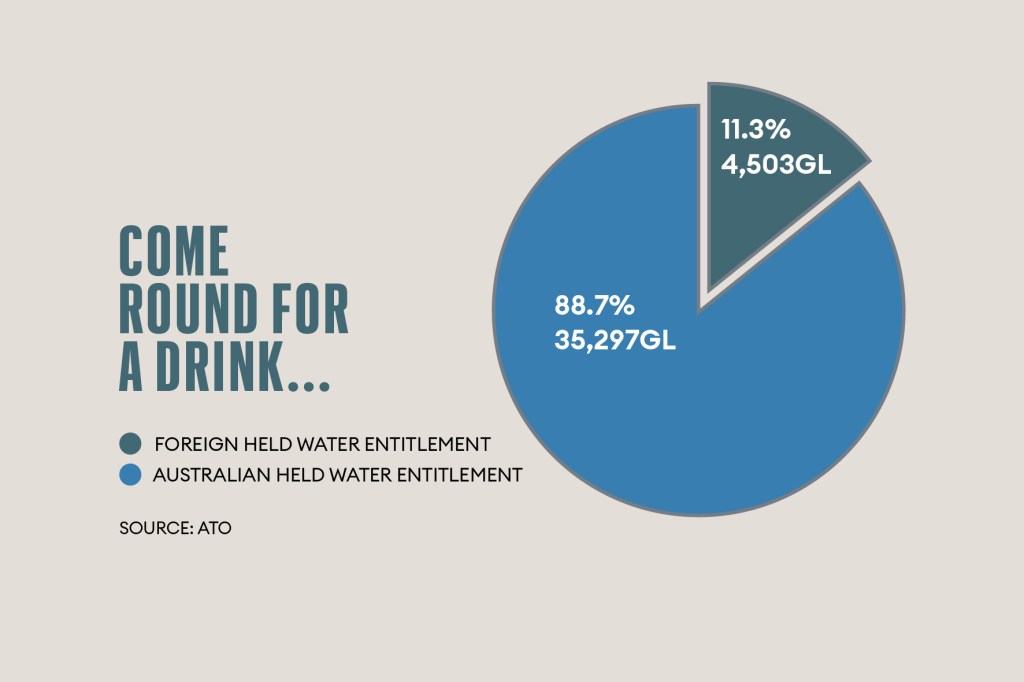

This market allows foreign ownership, and as of 2023, 11.3% of Australian water entitlements were held overseas, which amounts to more than double the maximum capacity of NSW’s Warragamba Dam, the primary source of water for Greater Sydney. These entitlements were used predominantly for agriculture (69.3%) and mining (19%) according to the ATO’s Register of Foreign Ownership of Water Entitlements.

In contrast, in the agricultural region of Northern Victoria, the Commonwealth of Australia dominates ownership at approximately 31%. However, much of this is directed towards environmental conservation.

In December last year, the Australian Parliament passed the Water Amendment Bill to ease tensions between competing interests, which claims to offer “more time, more options, more accountability, and more transparency” regarding water use and allocation in Australia.

One critical point is that it “repeals the limit on the Commonwealth’s purchase of water access entitlements”. According to the bill’s digest, this has been controversial because: “farming and irrigator groups remain strongly opposed to the purchase of water access entitlements by the Commonwealth.”

The bill is also designed to develop new insider trading prohibitions, new data reporting obligations and checks and balances on market manipulation.

Despite changes in the market system, domestic and stock rights are ensured under the Water Management Act. The right applies when one owns land adjoining a river, lake or estuary frontage or overlying an aquifer and allows individuals to take and use water for domestic consumption and non-intensive stock watering without a water access license or water use approval in most cases.

This story featured in Issue 9 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.