Jared Pohl is Director and co-founder of ECP Asset Management – an active equity specialist launched in 2012 and now with more than $3 billion under management. He spoke to Stewart Hawkins about the challenges of working in a volatile market, the opportunities and dangers of AI, the nuances (and potential costs) of trading ethically and why he finds joy in investing.

This story was featured in Issue 17 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

What are your fundamentals as an investor?

Any professional money manager should be able to articulate what their fundamental economic reason for being is. It can’t be emotive in any particular way. Ours is that the underlying economics of a business drive long-term investment returns. We’re looking for businesses that are expanding their economic footprint predictably.

We think the most sustainable way, particularly for long-term wealth creation, is companies that are in the growth phase of their life cycle. Companies that are taking or creating new revenue pools, are taking the share of customers, creating new markets, and investing in deep markets. Companies expanding their economic footprint as they reach scale are increasing their competitive advantages.

They’re not ripping costs out of the business to expand their economic footprint. They’re not generally growing through acquisition. It’s not companies using financial engineering to generate those economic expansion returns.

It doesn’t necessarily translate to short-term performance, but in the long run, it tends to be structurally generative of alpha.1

Would you describe yourself as a long-only investor?

Yes. But very concentrated.

What is your stock universe then?

Our philosophy kind of reduces that set quite materially. If you think about what we were saying before, they tend to be companies that are largely mid-cap bias, so they’re smaller. And we want smaller companies to grow into bigger companies. It doesn’t mean we won’t own a Microsoft or a Google, because [there are] such big markets that they can grow into, so you don’t want to say no to anything.

But we tend to focus on more things in that smaller end of town, just to give us longer runways of structural growth.

There’s probably [about] 2000 [companies], roughly, on an accounting measure that we would look at, indicating that they would fit our process. But, when you start to think about our philosophy and the areas we want to be in, we don’t want to necessarily be in biotechnology or infrastructure or REIT-related things, mining exploration, energy, that narrows it down quite quickly.

Then there are probably a few hundred names globally that would be in the sweet spot for us to focus our attention on. Then of that, we have in the portfolio as it stands today, [about] 30 names in the global portfolio, and we’re constantly looking for new opportunities that we could add at the appropriate time.

We’re in a volatile market now. How are you trading it?

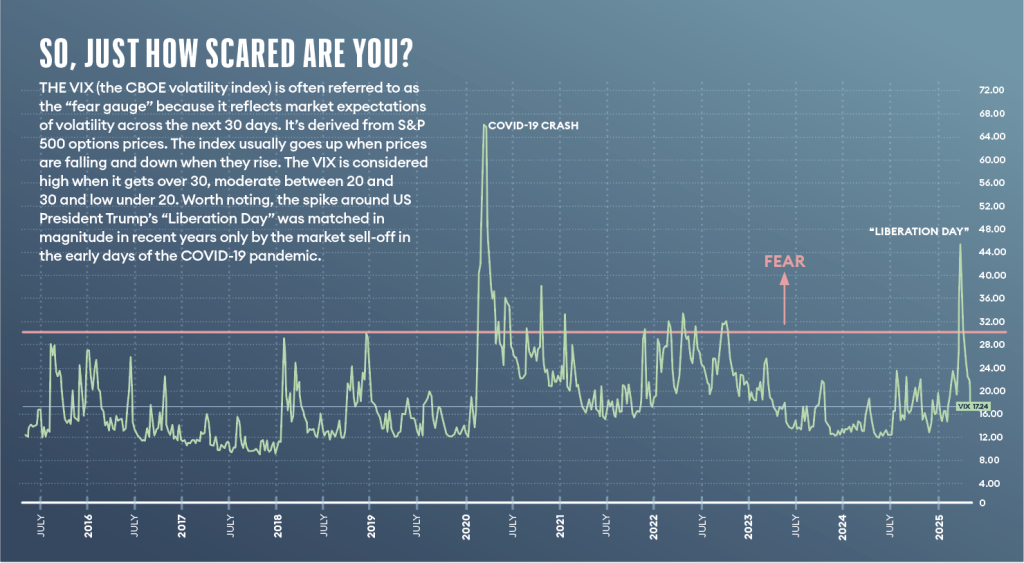

I think that volatility has become a feature of markets, and it’s become more and more of a feature since the GFC. Pre-GFC, a one or 2% move was a massive move. I mean, [now] you’re having high double digit moves on the day.

And, I think a big part of that comes down to the amount of embedded leverage in the system.

[But] the longer-term intrinsic value of, let’s say, Google doesn’t necessarily change that much daily. So why should the share price change that much day to day? And so the fundamental managers tend to be playing off the tension of longer-term value versus short-term market dynamics.

If you can do it well, you can make money. But the thing that you need to do then is to pick the right assets. We want companies in the growth phase of their life cycle, so they don’t tend to be as affected by macro events.

These are companies that are growing their footprint. It’s more likely they’re going to generate revenue through taking a share of a market, which somewhat insulates them from the ongoing macro. We didn’t trade much after [US President Trump’s] “Liberation Day”.

Now things seem to be a bit more stable, and if you look at that, the tenure of the [yield] curve looks normal, even though it’s kind of steepened, it’s within the realms of what it’s been over the past decade.

The five-year breakevens2 are pretty consistent. They say that they’re implying market inflation is going to be roughly around 2.5%.3

What about the USD? Concerning at this point?

I guess the biggest question is the status of the US dollar as the global reserve currency, for me, that is probably the biggest thing that could change.

My sense of what [is] happening is that people will just redraw supply lines. We’ve done it once [during] COVID-19, and maybe what ends up is bilateral trade deals just get done everywhere else, and so the reliance on that US consumer is lessened. It might even be a good thing in the end.

We don’t say, “Okay, US dollar’s up, or Aussie’s down, or whatever, that’s bad. Let’s go and find sectors that will benefit,” at all. [At] the moment the AUD-USD, for example, is flat, we don’t take a view. We just wash that through our numbers and say, “Okay, if everything is as it is today, where long-term rates are, our expectations are, what does that do to our current valuations? And then let’s allocate capital accordingly to that.”

What about broad geopolitical risks? The Middle East, China and Taiwan, India and Pakistan, and Ukraine?

I don’t think anyone likes war, and I think the world’s a better place if we’re all trading and getting along, but it’s been a while. There’s definitely going to be some kind of conflicts around, whether it’s critical minerals or Putin saying, “Well, you’re part of Russia.” Regarding geopolitics, we have no direct exposure to Pakistan or India. We don’t have any exposure to Russia, Ukraine and/or Israel.

Semiconductors are super crucial for everything that we do, and you need to be on the bleeding edge of that. China’s doing its own anyway, ex-TSMC4, but [they are] such a critical component of how we live our lives today. But you have seen TSMC building plants in the US and committing capital to the US, Japan, etc. I don’t know if what [US President] Trump’s trying to do is get to a point where they can be ready for something if it does happen. Would Xi Jinping be willing to have a hot war with Taiwan? I don’t know. Who knows?

On TSMC, what are your thoughts on where that company’s heading, given its potential pivotal nature in the chip industry?

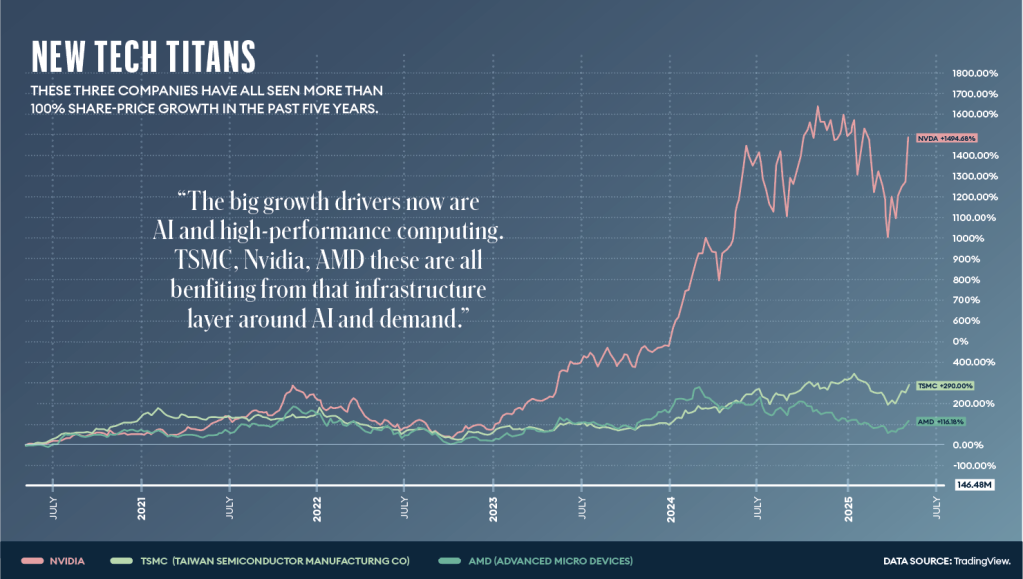

The big growth drivers now [are] AI and high-performance computing.

TSMC, Nvidia, and AMD5, are all benefiting from that infrastructure layer around AI and demand. Even though I think there’s been billions and billions spent, that will continue to go as models get increasingly more complicated to train.

There’s still a benefit in training. We thought we had reached that peak, and then Elon Musk came out with Colossus, for example. He said, ‘Well, look, we’re just going to build the largest computer and really go hard on the training.’ The things that have slowed down are phones and certain kinds of server nodes.

As far as we can see, there is still a big runway for demand, and TSMC is a key player in that space.

What do you see happening in the Australian market?

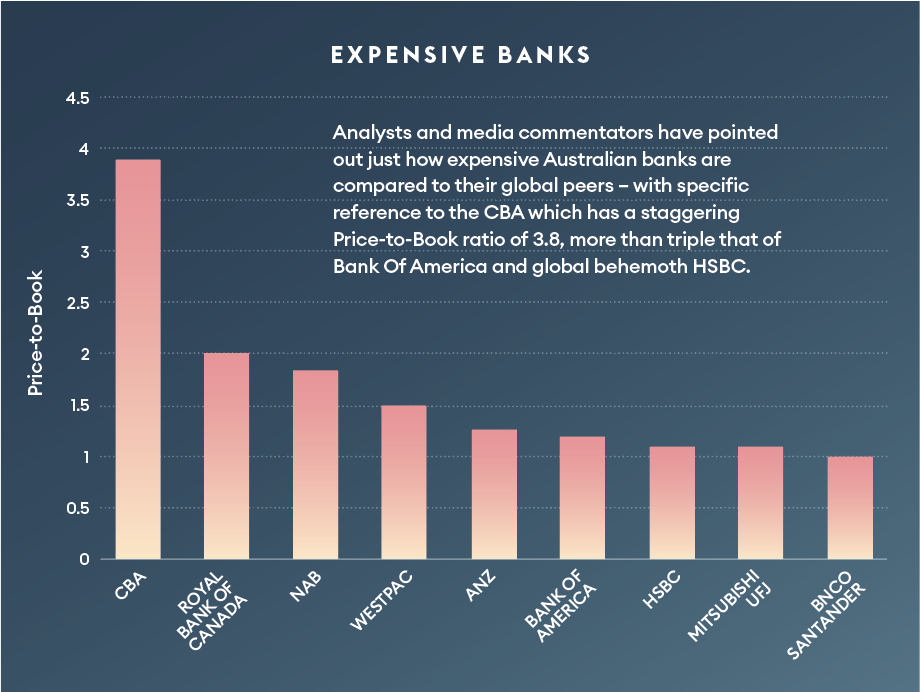

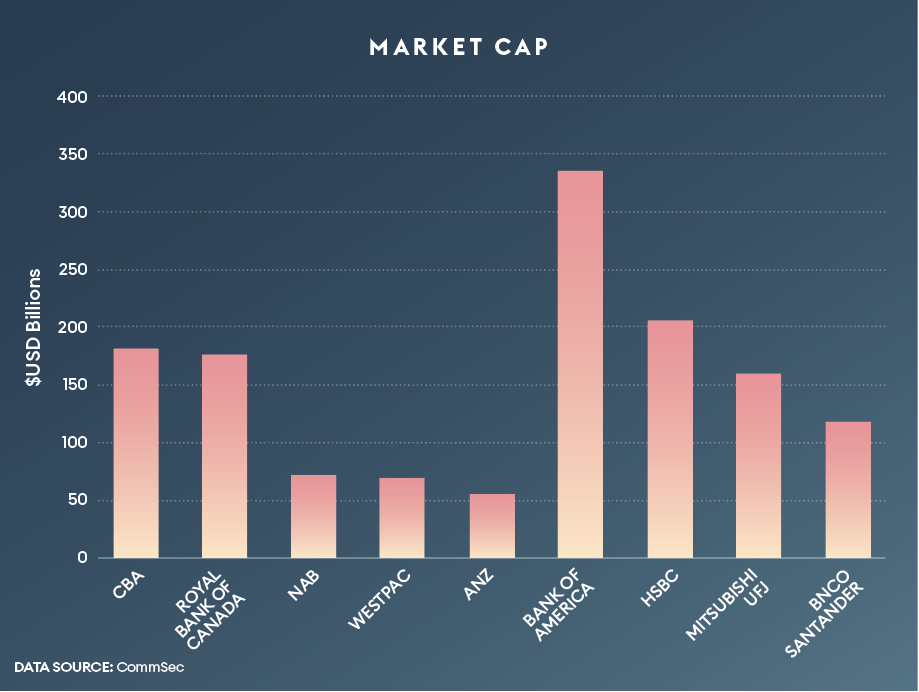

The Australian market’s a funny one. The kind of shorthand version is that it’s a bet on rates and commodity prices. I don’t think anyone would have believed that CBA6 could be the most expensive bank in the world. There’s been a dislocation through the regulatory environment, and I don’t think it’s going to ease up under [the newly re-elected] Labor [government].

[The] Your Future, Your Super test, does mean that the big asset allocators in Australia, the superannuation industry, are subject to certain tests that drive behaviour, tend[ing] to allocate [to] hug around benchmarks because if they don’t, they get acquired and merged. If you wanted to force mergers in super funds, you could do it in other ways. You don’t need to do this and then provide disconnects in the market.

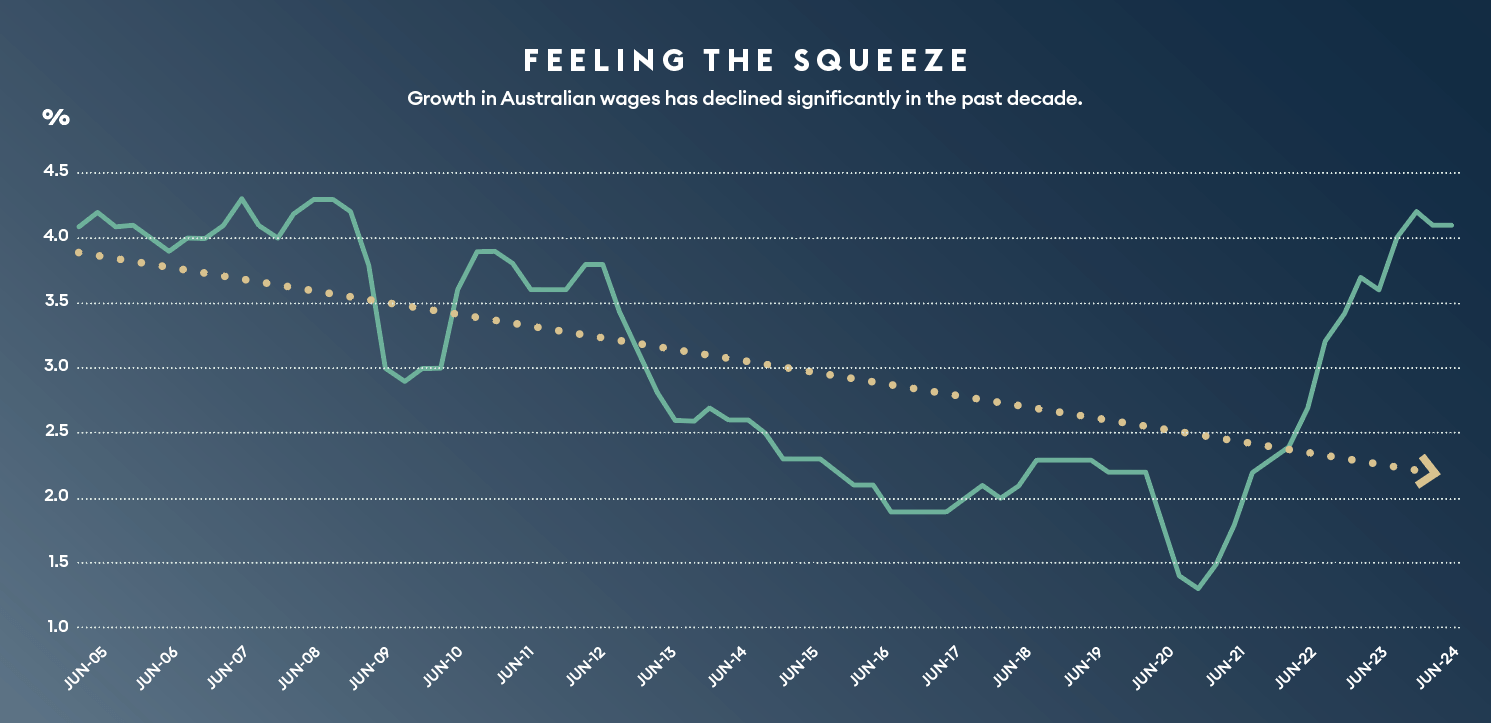

The big question for Australia is the efficiency of the market. Productivity growth is a big thing, and it’s something we’ve been speaking about for a while.

From an investment perspective, there are still some globally competitive, unique assets in Australia, and we want to allocate to those, not necessarily the things like CBA and the banks, because they are so expensive. As an active manager, the asymmetries for us are just so shaped to the downside that why would we want to own them? But we do things pretty well here. We’ve got some pretty good market products we can export, whether it’s healthcare, financial services, technology, and we are investing in advanced industries like quantum. Australian universities [are] quite at the leading edge of this. You’ve got the National Reconstruction Fund of Australia, they’ve got a mandate to do investment in these sorts of things. So we should be allocating capital there, permanent capital, to make us much more competitive globally, so we’re not just a picks and shovels kind of economy.

I think Australia’s still in a good place, but it could be better.

The market’s getting quite narrow; we haven’t seen a lot of new [listings]. Guzman y Gomez listed – that’s probably the most successful in the last six months, but before that, there wasn’t much. The way that we manage money, we don’t need a hundred new things a year. One or two a year is great.

There are a lot of really good companies here that have just stayed private longer. And a lot of that’s also to do with the Your Future, Your Super test, the way that allocations to private assets have increased, so they don’t have the volatility in returns.

What won’t you invest in? Where do you draw the line in the sand? Given that equity can be considered permanent capital anyway, what does that line in the sand mean?

I guess there has to be a cost to having morals, right?

It’s easy to say you can buy a coal company at one times earnings, but has that changed the need for coal companies in Australia? No. I think a lot of the changes are regulatory requirements. The capital markets can help bring ideas to fruition, but I do believe that the regulation and the role of the government should be to force certain changes.

The role of the capital markets should just be to maximise returns. Now, we obviously have views, there are certain things we just won’t invest in, and it comes back to the cost of having morals. We won’t invest in weapons manufacturing, but you can see both sides of the coin there.

Should Ukraine have weapons? One hundred per cent, they should be able to defend themselves, but should that be where I’m allocating my capital? I guess that’s just sort of a different decision. We’ve got a broad set of exclusions where we don’t think that they’re a net benefit to society: weapons manufacturing, alcohol, tobacco, and pornography. It’s not because we don’t think we can make money there, and we don’t think that there are good companies there, that’s just the position we’ve taken.

On a country level, it is more about the rule of law and property rights. We tend not to be exposed to developing economies, but it doesn’t mean we won’t. Rather than asset allocation decisions, they’re probably more risk management.

Exclusion is a big part of what we’re doing, but engagement’s important too. So, we engage with companies on the things we think matter. A big one for us is governance. What are the incentives to management? I’ve got a meeting coming up with an Australian company where I think the incentive structures are wrong, so we’ll try to guide through voting and stuff like that and adjust the incentive structures to lead to the right outcome.

We try to find the best businesses we can. So there’s generally not a lot of room for engagement because they’re doing good things. Companies that are screwing their customers over, or their stakeholders, don’t tend to perform well.

It’s tricky to go in and say, “All right, energy provider, you’ve now got to go green,” or something. It takes time. There’s got to be a market mechanism for this. Do the customers want green energy?

You can pressure the companies all you want, but it comes down to the interface between government regulation and capital markets.

What is your most important message for investors?

Enduring value doesn’t change as much as underlying share price performance. If your readers are investors, they need to know what kind of investor they are.

Things are moving so crazily at the moment. It’s very tricky to find out what’s true and not true, so you need to trust in your ability to filter through things on a first principles basis and work that way and then not necessarily get swayed too much.

The core message is work on getting that right, and the risk kind of takes care of itself. That’s the joy that we have every day, right? To sit there and constantly test ourselves and see how we can improve our information processing.

The risk is to outsource all of that thinking to AI and these sorts of things,

but I think that’s probably going to end up with a worse result than if you think about it yourself.

We’ve got a pretty good computer up here (points at his head), it’s been developed over millennia.

There are things that it does really well.

Notes

1. Return above benchmark or above expectations given an asset’s risk profile.

2. Difference in yield between 5-year sovereign bonds and equivalent inflation-protected bonds. 3. At the time of the interview.

4. Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Company, market cap at time of going to press approx. $US850 billion. [TWSE:2330;NYSE:TSM;LSE:OLCV]

5. Advanced Micro Devices [NASDAQ:AMD]

6. Commonwealth Bank of Australia. [ASX:CBA] – on a price to book [P/B] ratio, the bank was trading at around 3.2x. P/B measures a company’s market cap compared to the value of its shares.

This article represents the views only of the subject and should not be regarded as the provision of advice of any nature from Forbes Australia. The article is intended to provide general information only and does not take into account your individual objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance. You should seek independent financial and tax advice before making any decision based on this information, the views or information expressed in this article.

This story was featured in Issue 17 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to secure your copy.

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.