What does it take to bring a Tasmanian tiger back from the dead? A Texan tech entrepreneur, a Nobel prize-winning breakthrough in gene editing, and a partnership with the world’s greatest geneticist. Also, investors like billionaire Thomas Tull, the Hemsworth brothers, an Australian-based family trust, and the CIA.

This article was featured in Issue 8 of Forbes Australia. Tap here to grab your copy.

When University of Melbourne Epigenetics Professor Andrew Pask got a call from American tech entrepreneur Ben Lamm about going to Texas for a meeting with a company called Colossal Biosciences, there was one name that convinced him to get on the plane.

“George Church. He’s like an absolute icon of genetics,” Pask says.

Church developed the first direct genomic sequencing method in 1984, leading to the Human and Personal Genome Projects. A professor at Harvard and MIT, Church is renowned for his work in synthetic biology, genomic science, chemistry and biomedicine.

“He’s a hero of mine and was involved in the project with Ben. I was curious about the DNA technology because that’s the roadblock to making this happen.”

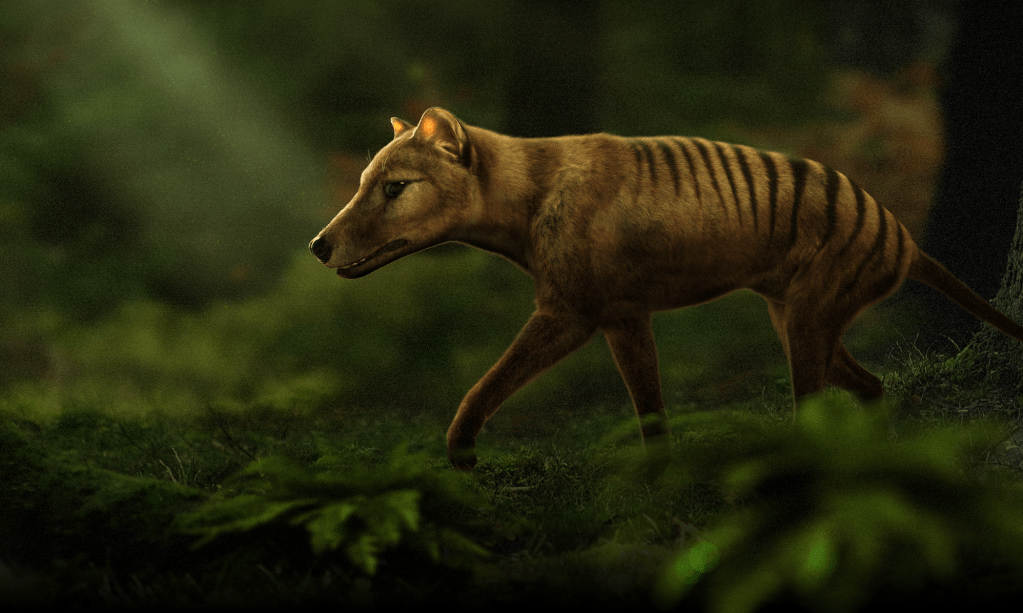

The project Pask speaks of is one he has been ‘dabbling in’ during his spare time over the past 20 years. He has long aspired to bring a Thylacine – better known as a Tasmanian tiger – back from extinction.

“I was confident that we could do all of the marsupial surrogacy, and assisted reproductive technology, and the cloning, and the stem cell side – we can do that,” says Pask. “But the DNA editing bit was going to be super challenging with our budget.”

The budget Pask and his team at the University of Melbourne were working with came from a donation from the Wilson Family Trust in March 2022. The Trust pledged $5 million over 10 years, enabling Pask to establish the Thylacine Integrated Genetic Restoration Research (TIGRR) laboratory at Melbourne University.

Five months after that investment, Colossal Biosciences announced it was also contributing $10 million to the Thylacine cause.

“You need big money to address these issues,” says Pask. “It needs colossal investment. We have limited funding in science. We don’t have the mechanism to fund big ideas, blue sky thinking.”

Luckily for Pask, blue-sky thinking is what serial entrepreneur and Colossal founder Ben Lamm does best. Over the past 13 years, he has built, run and exited from five businesses, three of which were acquired by NASDAQ-listed organisations. Lamm says he is driven to ‘solve the most complex challenges facing our planet.’

Massive problems require massive amounts of funding, and Lamm has shown he is the man for the job. Colossal raised $225 million since launching two years ago, Lamm says. Valued at $1.5 billion as of its last fundraising round last year, the company is in a strong financial position to hire the brightest minds worldwide capable of solving animal extinction.

Anything we do that has an application to conservation, we are giving that technology to nonprofits, conservation groups and governments.

Ben Lamm, Colossal Biosciences Founder

“We have 115 people, we have 70 plus scientific, academic, and conservation advisors,” says Lamm We fund 60 postdocs in an academic lab. It takes an international consortium.”

It is a shared goal of Colossal and Pask’s TIGRR that the Thylacine will again walk the earth in 2028. That timeline is only feasible because of a transformative breakthrough in gene editing research that has taken place over the past decade.

A seminal research paper published by Swedish and American scientists Emmanuelle Charpentier and Jennifer Doudna in 2012 led to the breakthrough. Charpentier and Doudna’s work on Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats, or CRISPR as it is known, won the 2020 Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Also called ‘genetic scissors,’ CRISPR can be used by geneticists to change the DNA of animals, plants and microorganisms.

This discovery in gene editing paved the way to the rebirth of the Thylacine and the de-extinction of the other two animals that Colossal is working on – the woolly mammoth and the Dodo. CRISPR makes it possible to take genes similar to an extinct animal and ‘cut’ or ‘edit’ them into the same genomic sequence they once had.

THE 9 STEP PLAN – How to de-extinct the Thylacine

- STEP 1: Publish the genome (done)

- STEP 2 : Sequence its closest relative, the dunnart mouse (done)

- STEP 3 : Identify differences in closest relatives & edit genes

- STEP 4 : Derive stem cells for dunnart mouse (IN PROGRESS)

- STEP 5 : Develop marsupial assisted reproductive tech (IN PROGRESS)

- STEP 6 : Use living stem cells to create embryo.

- STEP 7 : Transfer embryo into uterus of host species.

- STEP 8 : Gestation and birth of thylacine from host species.

- STEP 9 : Bottle feed thylacine while development continues.

”CRISPR has created this excitement and infusion of capital and allowed for the advent of new technology and advancements in a lot of genome engineering technologies,” says Lamm. “Sometimes it’s multiple edits to a gene, and sometimes it’s even doing DNA synthesis, where we’re writing a piece of DNA, editing it, and swapping that in.”

The work that Lamm and Church are spearheading in the Colossal laboratory is pushing the frontier of how CRISPR is being used in the real world, according to Pask.

“Nobody is using the technology on the same scale that Colossal is. This is the next level. And to do that, it requires a lot of finessing of those tools. That’s what has been the game changer for us – we needed to engage with real cutting-edge technology to bring these projects to life.”

Balancing the tension between open-source academia and providing returns and profit to investors is a tightrope Lamm seems at ease walking.

“If there are applications for human health care, then we are monetising.” The 41-year-old entrepreneur points to Form Bio, a life sciences software platform spun out of Colossal last year. It raised $30 million in its Series A funding round.

“Anything we do that has an application to conservation, we are giving that technology to nonprofits, conservation groups and governments,” says Lamm.

Pask says this makes it easy for him to work with the Colossal corporation because the tools he is developing are related to conservation and, therefore, are open-source, allowing him to publish academically. He recalls his initial meeting with Lamm and the synergy that the two felt about solving de-extinction despite being from very different backgrounds.

“I’m honed in on the critical issues we must solve to do this. And I think Ben’s superpower is his ability to break down these complex big issues into achievable units. It was amazing how quickly you could distil down what I spent 20 years learning,” says Pask.

In addition to working closely with the scientific community, Lamm has prioritised engaging with other stakeholders who would be impacted by de-extincting the woolly mammoth.

Given the implications of reintroducing a 3-meter, 6-tonne mammoth into an ecosystem that has not lived for 4000 years, Lamm says it has been very important to listen to multiple perspectives.

“[What] we learned very early on was to work with groups like private landowners, local government, and indigenous groups,” says Lamm, who recently visited North Dakota after a mammoth tusk and bones were found in a lignite mine.

“If we bring back mammoths or other extinct megafauna, it’s crucial to get these groups’ feedback now and let them help teach us what is important to them.”

Remains of the animal known to roam North America during the Ice Age have also been found in the perma-frost as far north-west as Alaska and as far south-east as Vermont. A mummified baby mammoth said to be 30,000 years old was unearthed from the frozen tundra in the Yukon district of Canada in 2022.

The first step in Colossal’s mammoth de-extinction process is to find well-preserved animal remains in Alaska and Siberia. The genome can then be sequenced from multiple samples to ensure accuracy.

The closest living relative to the mammoth is the Asian elephant. That genome has already been sequenced and can be compared to the woolly mammoth’s. Eventually, CRISPR can be used to edit the Asian elephant’s genes to replicate the mammoth’s genes.

If the de-extinction is successful, Lamm sees the cold climate and grass plains of North Dakota as an ideal location for rewilding the mammoth. The state has a deep connection to the animal, partly because of its significance to the native American population.

This is another area in which there are parallels between North America’s extinct mammoth and Australia’s Thylacine. Australia’s First Nations and Torres Strait Islander populations also have close ties to the extinct species. Pask spent time with Indigenous communities in the Northern Territory to better understand their connection to the animal.

“They’ve got one of the richest histories with the Tasmanian tiger because it’s in the cave paintings all through the north,” explains Pask. “It played a big role in Dreamtime creation stories. They have this deep spiritual connection with the tiger.”

While the Tasmanian tiger did not pose a threat to humans, it was hunted and exterminated because European settlers believed it was a threat to livestock. The prevalence of dingos, mange and habitat destruction throughout Australia also contributed to the demise of the Thylacine.

In the case of the woolly mammoth, hunting by humans and the development of spears are two causes of its decline. A warming climate, rising sea levels and vegetation scarcity are others.

Midwest states like North Dakota, where mammoth fossils have been found, contain enormous deposits of lignite coal and are rich in oil, gas and petrol. Mining dates back to 1873, and mammoth bones are still found in mines today. The North Dakota Development Fund invested $3 million in Colossal this year, and Lamm says Colossal has plans to set up a hub in the US state.

Another government organisation in the US that has invested in Colossal is the Central Intelligence Agency. Its venture capital fund, In-Q-Tel, has a specific interest in synthetic biology of complex biology such as animals. A blog post from the CIA’s VC division states, “It’s less about the mammoths and more about the capability.”

“Solving the challenges that must be overcome in engineering animals and plants will unlock programming the physical properties of wood to improve building materials, preventing the extinction of not-yet-extinct but endangered animal species and sequestering carbon from the atmosphere. It will further enhance crop species to tolerate increasingly severe climatic changes, and curing human diseases such as sickle-cell anemia, beta thalassemia, Duchenne muscular dystrophy, and many kinds of cancer.”

Chris Hemsworth and the family investment vehicle have invested.

Ben Lamm, Colossal Biosciences Founder

Colossal’s lead investor is billionaire Thomas Tull, known for owning Legendary Pictures, which produced the Dark Knight, The Hangover, and Jurassic World. VC firms Draper Associates, Boost VC, AtOne Ventures and Jazz Venture Partners have also put in funds.

Other well-known investors include the Winklevoss twins, Paris Hilton, and the Hemsworth brothers.

“Chris Hemsworth and the family investment vehicle have invested,” confirms Lamm, who spent the weekend after SXSW Sydney with the Hemsworths in Tasmania.

It wasn’t the Texans’ first time to the island home of the animal he is working to bring back into existence. Each time he has boots on the ground in Tasmania, the locals work to convince Lamm of supposed sightings of the tiger.

“They love it,” says Lamm with a smile. “So much so that I called Andrew, and I was like, ‘Hey, so, are you sure it’s extinct?’ Because I talked to a lot of people. They told me it’s still here.”

Unlike the woolly mammoth of which there is no video or recent interaction with humans, the mythology and connection to the Tasmanian Tiger is within grasp because extinction occurred only 90 years ago, says Lamm.

“It’s just barely out of memory, right? Barely out of reach,” says Lamm.“We still have film of it. After I was down there, I was even more excited about the project.

“This has been a really interesting kind of world of discovery for me. Not just in developing technologies and advancing technology-oriented science, but there’s also so much around this project. They are beautiful animals. Super iconic, super, super cool.”

Forbes Australia Issue 8 is out now. Tap here to secure your copy.