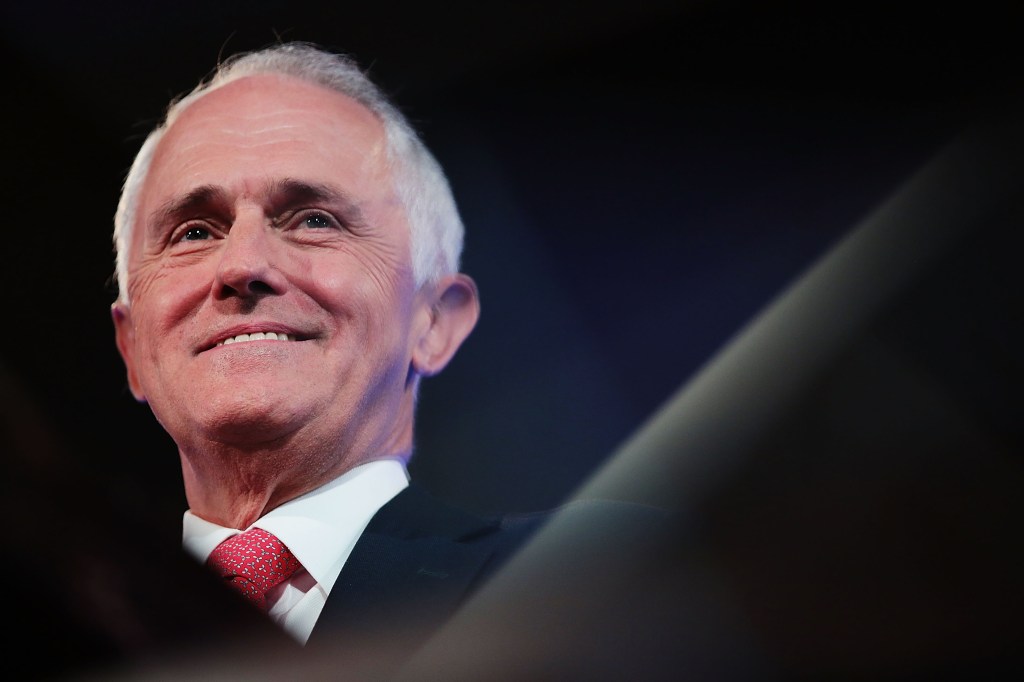

In a wide-ranging interview, former Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull talks to Forbes Australia ahead of joining the line-up at The Tax Institute Tax Summit this week.

“The sanctions and the economic dislocation arising from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have been severe enough, but the rest of the world’s economic ties with Russia are modest compared to the economic ties with China. China is many, many more countries’ largest single trading partner. The effects would be devastating, leaving aside the prospect of a nuclear conflict.”

– Malcolm Turnbull, former Prime Minister of Australia

The Hon. Malcolm Turnbull AC served as Australia’s 29th Prime Minister from 2015 to 2018. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party of Australia. Here in a wide-ranging interview with Forbes Australia , he discusses the possibility of tax reform, the difficulties of tax reform and the impacts of inflation and geo-political conflicts across the globe.

What has got inflation to this point?

“The biggest single factor is energy prices and in addition to that, supply chain issues, which had their origins in the pandemic, exacerbated by the factors that have been driving higher energy prices, with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

“The problem with inflation generally is that it undermines the value of people’s income. Depending on how you are holding your assets, they might be appreciating with inflation, or if you are holding cash, or you don’t have a lot of assets or you are spending your entire pay packet every month, you are going to be going backwards.

“Tax revenues are a function of economic strength. If the economy is stronger, businesses are making profits, more people are employed, if people are working overtime, they are getting paid more, tax revenues are higher. If they are consuming more, GST (Goods and Services Tax) revenues are higher. A good strong economy is good for government revenues.

“But if inflation is higher than the growth of a person’s income then they are going behind in real terms.

“To curb inflation central banks have been raising interest rates and there is speculation that the US will go into recession. Everyone, I think would agree, that the US Federal Reserve was slow to act on inflation and there is now a real concern that it is overdoing it in terms of the interest rate response.

“As rates go up, it has an impact on the cost of money, stocks will go down, capital goes up, and that can slow economic activity.”

Was the Reserve Bank of Australia late to the party?

“I think the Governor (Philip Lowe), and I think he has pretty much said the same, that if he had his time over again, he wouldn’t have said that rates would be stable for as long as he suggested. It might have been wiser not to have made a prediction like that. I think there’s been a number of things occur that people were not anticipating, one of which is the war.

“Inflation mostly provides challenges. There’s a reason why central banks have inflation targets of 2-3% and not 7-8% or 10-11%. Higher inflation does undermines the value of saving, the value of wages. You want to maintain inflation within a modest band, and the central banks are trying to get it back and I think they will over the next 12 to 18 months, assuming no other catastrophes occur.

“It’s hard to factor. You can be alert to wars or geo-political crises, but it is hard to punch them into a model. You have to have policies, whether it be monetary policy, or fiscal policy, or energy policy, that are flexible and resilient enough to withstand crises, if and when they occur.

“It was always possible that there could be a crisis with Russia, particularly with Ukraine, certainly since 2014 when they invaded and seized Crimea. That’s eight years ago. During that time, Western Europe continued to make itself, more and more dependent on Russian gas. With the benefit of hindsight, having seen Russia move against Crimea, Western Europe, particularly Germany, should have seen that this was no longer a theoretical possibility of a war in Europe.”

Should Australia be more wary of the possibility of hostility between China and Taiwan?

“I think everybody is very alert to that. But a Chinese invasion of Taiwan, and whether it extends to a wider war, it would be hard to see how that would not send the world into a global depression. If China were to seek to forcibly incorporate Taiwan into the People’s Republic of China, even if that did not result in a wider war between the US and China, it would certainly result in an acceleration of the economic decoupling that we are already starting to see. It would result in sanctions that would increasingly divide the world between economies that were dealing primarily with China, or primarily with the US and her allies.

“The sanctions and the economic dislocation arising from Russia’s invasion of Ukraine have been severe enough, but the rest of the world’s economic ties with Russia are modest compared to the economic ties with China. China is many, many more countries’ largest single trading partner. The effects would be devastating, leaving aside the prospect of a nuclear conflict.”

Do we need tax reform?

“The criticisms of Australia’s tax system fall into several buckets.

“One bucket is to say we should be raising more tax revenue generally. Government expenditure as a share of GDP is lower than it is in Europe and other comparable countries, but if you ask most Australians do you think we should be paying more tax, the answer is no.

“The other argument is about the sustainability of the tax base. The criticism is that we generate too much of our tax revenue from personal income tax and the argument is that we should generate more from a consumptions tax, which in our case is the GST, but many would say the GST base is too narrow. There are a lot of things that are not covered, such as health services, education. At a theoretical level a goods and services tax should be on everything, as it is in many other places.

“If you have expenditure increasing in the areas that are not subject to the tax, then the tax base becomes even more attenuated.

“With personal income tax if strong growth in salaries is occurring in areas where labour is declining as a percentage of the overall economic activity – take the mining sector where miners can earn good money but there are fewer of them because of the amount of equipment and technology being implemented across the sector – and the sectors where employment is expanding, such as in services including health and hospitality where income levels are lower, hence the tax take is lower.

“You have to find tax reforms that are seen as fair, but that justify the political pain involved.”

– Malcolm Turnbull

“You have to be practical about tax reform. It is often said that an old tax is a good tax because people are used to it.

“The changes I made in 2016 to superannuation to make it more equitable, it was literally 4% of superannuants were worse off as a result, literally the richest 4% of Australians, and the political grief we got for that was massive. The problem is that you could look at a distributional analysis of any tax change and see the people that will be better or worse off. The lived political experience is that the people who are better off won’t have much to say about it and the people who are worse off will scream like hell. Whether you are in business, the media or academia and you say why doesn’t the government do something, well it is easier said than done. What you really need is a strong consensus of support.

“If you broaden the base of the GST or put up the GST, or both, and then lower personal income tax, the first objection to that is that you are increasing the cost of the GST on everything that anyone can buy, but then you are offsetting that by reducing personal income tax. That’s a zero-sum game.

“But then what about the people who are not paying tax, because they are pensioners, or on low-income or superannuants. You have to compensate them. It is hard.

“Inflation will push people into higher tax brackets, hence the term bracket creep, which is why in the 2018 Budget we made a series of changes to personal income tax, one of which was that by 2024-25, the second top bracket would come out.

“I think what we did in 2018 by legislating to get rid of that tax bracket, albeit in some years’ time, was a worthwhile reform. I know there are critics, but the so-called stage-three tax cuts are not benefitting billionaires, or for the top end of town.

“In Australia, we don’t have inheritance tax, we don’t have death duties, the family residential property has no capital gains tax on that, then other areas of reform could include negative gearing.

“I have never been convinced that changing the rules around negative gearing would make housing more affordable. The vast majority of people who are negative gearing are on middle incomes. If you want to cut it out, you are going to impact middle Australia in a big way. If you just deal with people at the top end and restrict it to a certain number of properties for example, the amount of additional revenue you will get is modest compared to what you are trying to achieve. You have to find tax reforms that are seen as fair, but that justify the political pain involved.”

This is an edited version of the conversation.