Piers Bolger, Chief Investment Officer at Infinity Asset Management, leads the firm’s multi-asset investments and is responsible for macroeconomic research. He spoke to Stewart Hawkins about the divergence of market performance and job growth in the era of AI, what that means for consumption and wealth and the effect on investment portfolios. Also how Australians can get on the AI investment train.

This story appears in Issue 20 of Forbes Australia, out now. Tap here to secure your copy.

What have been your long-term fundamental investment strategies?

We like to have more quivers at our disposal in order for us to be able to fire [arrows at] particular targets. That is critical because it does provide greater flexibility in the way you look at investment opportunities.

You need to have an element of risk if you’re trying to get a return profile across any asset class. If you’re investing in cash, you’ve got opportunity cost there potentially versus equity. That’s a risk management decision. You need to understand the risk that you’re taking on, and you need to be compensated for that risk, and that arguably then allows you to construct strategies that can provide a consistent investment profile. Then you really allow the eighth wonder of the world, being compounding, to work in your favour. You don’t sit there and do nothing.

If you’re looking particularly at an equity construct, we’re a quality growth manager in the way that we think about investing. The key elements associated with that are that you’re looking at the stability of earnings of individual corporates, the cash flow and the sustainability of that through time.

What are your thoughts on today’s investment environment?

I think 2025 has been a reflection of a more normalised year in the sense of rate moves and financial market performance, and it’s about really focusing on key thematics [and] the risk side of it within a portfolio context.

What are the key thematics?

It’s around growth, and it’s around the direction of the rate cycle, and what’s driving that clearly is inflationary expectations and the growth outlook. The other element that probably has been getting some airplay, that in our view will continue to get increasingly so, is the divergence between central bank policy, what central banks would like to see, versus what we’re seeing fiscally at a government level.

Central banks are trying to contain to some extent – liquidity to keep inflationary expectations at a lower end. Whilst we’ve got governments around the world spending – and that’s creating challenges on both sides of that demand-supply. That’s an important point for financial markets because of how you deal into that. You’ve got a massive increase in terms of the impact that AI is having on productivity and the labour market force.

To give you a really good example of that, if you think through ChatGPT when it was launched, it seems a lot longer than November of 2022, and you look at the performance of AI-related companies and the S&P 500 more broadly from that date, relative to job openings – they’ve basically completely diverged.

If you look through the performance of the S&P 500 since 2000 up until 2022, as you would expect, as the market goes up, job openings increase, and your hiring increases. We’ve seen a complete divergence of that post-2022.

What does that then mean for consumption? What does that then mean for the spread of wealth within the economic environment? They’re sort of broader, longer-term issues, but I think that they’re going to have an impact in terms of individual financial market performance and ultimately how we think about building investment portfolios.

What dangers do you see emerging? What do you see as the spark points?

Markets have had a very good way of muddling through geopolitics over time, but it’s clearly something that you can’t price for because you just don’t know where that will end up. Clearly, China have said by 2047 that Taiwan will be effectively backing towards China. How that plays out over the next 20, 25 years, who knows? But it is a sensitive topic.

It’s interesting, clearly, when you look at AI and TSMC and the importance of that as a company globally and what they’re doing as a company in terms of setting up new factories and the like in the US, as an example, to provide some protection on, say, chip production and the like.

You need to be cognizant of it and you need to be able to articulate strategies around it, but you can’t let it drive your decision-making directly.

The big conversation now is AI – are the products really delivering yet? Are they dangerous? If so, how should they be regulated? Are valuations too high? Is it all a bubble about to pop?

It’s a really interesting one. We just think computer quantitative power has been with us for many decades.

Going back to [my] university days, when you had the basic technology to help you write your essays and those sorts of things. We’ve seen that evolve. Where we are today, we are now starting to see the extension of it. By that I mean you’ve got it in terms of computing power, GPUs [graphic processing units], chip manufacturing, really, that sort of the thing, let’s call it ‘the beginning phase’.

We’ve started to get that increased demand, and the computing power is such that it’s now rolling into other areas, such as memory. You’re now requiring greater levels of memory capacity, and that brings different types of corporations and different types of technology to deliver that. Then you’re going to need greater levels of power.

[Then there’s] this whole concept now around datacentres – and where they access power. We’re seeing an energy shift now starting to come through to be able to provide power to the datacentres that can then provide the capacity for the GPUs and the chip manufacturing, and then you’ve got the networking side of it as well.

You’re also seeing that, particularly in terms of how companies such as NVIDIA are effectively going into other parts of the tech ecosystem. When we think about the AI landscape, we really look at it as a broad concept as opposed to it just being focused very much on the processing side and what can actually be generated from the individual GPUs. It’s got a lot of breadth to it.

Are we in a bubble? Are we like the dot com? We don’t think we are in a similar vein to where we were in 1999 into 2000, where we saw a lot of companies in the Australian market, as a case in point, that were arguably shells doing a back door listing as a tech company: no cashflow, no balance sheet, lots of leverage.

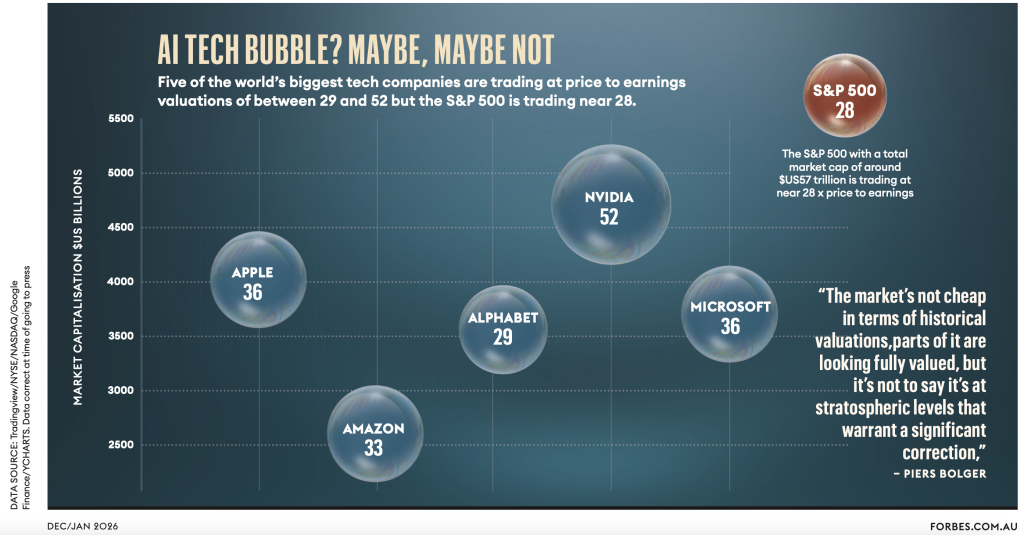

These [AI] businesses are real, and they have real earnings capacity and they’re delivering real tangible benefits to consumers and to corporates and to society as a whole. We don’t put that in the same context as what we saw back in 2000. Valuation’s a really interesting one. What do you pay for NVIDIA? What do you pay for Amazon and Apple? If you look at Microsoft, it’s always by and large traded in the mid-35 to 40 times [price to earnings], and we aren’t seeing a material shift in its forward earnings multiple over the past 10 to 15 years.

Thinking about how much it’s spending on AI along with other corporations, yes, the overall multiple of these businesses is high relative to, let’s say, what the S&P was over the past 20 years, but it’s not necessarily high [relative to] its individual history. As their market caps have grown, because people are investing, clearly, the valuation on the market has increased. If you actually looked at the S&P on an equally market-cap-weighted basis, it’s really trading at 17 to 18 times forward earnings, not necessarily the 22 to 23 times that we are looking like at the moment. From our perspective [that] gives us a view that yes, the market’s not cheap in terms of historical valuations, parts of the market are looking fully valued, but it’s not to say that the market is at stratospheric levels that warrant a significant correction.

Markets are going to pull back, and we’re seeing that at the present point in time. You can’t have markets up 25, 30% annualised year-on-year without having some level of pullback. We think that that’s just a normal part of the investing landscape and that may impact those companies that have run harder than others and the companies that are probably the second derivatives, those that have really rallied off, let’s say a deal within NVIDIA or a deal with a Microsoft, those are the types of companies that may see greater levels of share price variability, because you’ve got to translate the deal into an actual earnings outcome and that can take many years.

So how big can this go? How much runway is here?

It’s a very good question. It’s probably well past my computational powers.

We just continue to see sort of bolt-ons that are starting to evolve and develop, so we think the runway is very significant. If you just think about one of the companies that we like… they’ve been able to use AI in terms of their [medical] imaging for diagnostic purposes and the speed by which they can get clinical results back to the specialist or your GP is phenomenal so a little development around the AI model to be able to assist in that has just incredible leverage for that one business.

And then you can look through a multitude of different types of businesses and industries, logistics, inventory management, you name it.

When you think about how big it can get, I’d make the point that it’s about how industries collectively will be able to utilise what it can bring, and the specialisation that it can bring to a particular market environment – that will be decades in terms of what that can be.

Ultimately, you want to see tangible cash flows and what you are paying for those cash flows, but the impact is going to be massively significant, but it will taper.

A good example of the tapering effect is the energy required.

We’re now starting to see some bottlenecks occur, hence why certainly the US, particularly, but other countries around the world are now pivoting back to nuclear as a means of power sourcing away from a traditional coal base.

As an Australian investor with Australian dollars, how do I get on this AI train?

There are businesses that you can own here locally that are utilising the AI theme within their construct. Every datacentre now is roughly costing about a billion dollars.

The build is becoming more complex. People do look at them a little bit like they’re an industrial warehouse, but they’re becoming larger and they’re becoming more expensive.

Healthcare is another example. You’ve got a multitude of businesses within the healthcare space that are utilising AI, whether it be in terms of diagnostics, whether it be in terms of the development of serums and the like.

You’re seeing it within financial services. If you’ve ever rung your local bank, you’ll see that you’ll be talking to a chatbot. They’re getting better and better in terms of their language models and their ability to process and be able to assist you in terms of your requirements, not necessarily needing any human intervention.

We’re seeing [it] in the consumer in the retail space, whether it be in terms of inventory management, logistics, these sorts of things. Our view is that it’s permeating all industries, and the direct concept in terms of can I own NVIDIA? Can I own a chip maker? You can clearly do that, but you can also own other companies and other parts of the industry segments that can benefit from that. Like mining, if we talk about rare earths, just in terms of Australia’s position, we mine roughly about 14% of the key rare earths. We have a wonderful opportunity.

Are there local Australian companies you can invest in that are in this space directly, as opposed to tangentially?

Not to the same extent that you’ve got [overseas]. We just don’t have the chip manufacturing capacity or capabilities here in the local market.

What’s your view on ETFs?

We like ETFs; we invest in ETFs across our portfolio. ETFs, ones that give you exposure into those companies. We think that that’s an entirely appropriate way to invest if that’s what the solution requires or that’s where individuals think that they prefer to be rather than try and isolate individual securities on that side of things.

Where else are you looking?

We’ve been increasing our asset allocation from developed markets to developing markets over the past 12 months. Emerging market valuations have been a lot cheaper than those of developed markets. Look at China, a good example, Hong Kong, there are lots of growth opportunities from that perspective as well.

If we just take DeepSeek in the early days of this year in terms of the impact that it had, you just take what [NVIDIA CEO] Jensen Huang [recently] said, that in his view, China will be leading the AI space in the next decade or so.

India has a growing and burgeoning technology IT sector, and we’re expecting that to also continue to mature. Defence is another really interesting one, and we’ve clearly unfortunately seen that play out, particularly in Europe.

The utilisation of drone technology is a case in point, and what’s occurring on that front as it relates to AI development. We absolutely expect that to continue at a pace, just given the cost-effectiveness of drone technology in multi-facet Defence architecture and the importance of AI within that.

Speed bumps, dangers?

I think the key one is that everyone thinks this can go to the moon with no recalibration. One of the great things about investing is that you’re not as good as you think you are, and people do get over their skis to a point, then have a bit of a fall.

If you and I are in jobs where AI is replacing us, that may be great for the corporate, but is that great for the individual? What does that then mean if we do lose our jobs in terms of our consumption behaviour? What does it mean in a family dynamic? What does it mean for retraining if required?

AI is moving at a faster rate than the re-schooling of what was historically done by individuals. I think that governments will become increasingly aware of that because ultimately the voter will decide on how that plays out.

What keeps you awake at night?

Thinking we’re in a Goldilocks environment when we’re not? People might articulate that we’re heading into a bubble, but they can never tell you when it’s going to end. I always spend a lot of time thinking about, well, if we’ve got it wrong, how do we manage that risk? And then how do we mitigate any drawdown?

What is your best piece of advice?

Just start. I’m firmly of the view that trying to time markets is a fool’s errand, and if you’re looking to build wealth, the best way to do it is to hasten slowly. Everyone’s got a barbecue pick, and I think that’s just garbage. Just start and build over time, and let the compounding impact deliver. And be consistent.

This article represents the views only of the subject and should not be regarded as the provision of advice of any nature from Forbes Australia. The article is intended to provide general information only and does not take into account your individual objectives, financial situation or needs. Past performance is not necessarily indicative of future performance. You should seek independent financial and tax advice before making any decision based on this information, the views or information expressed in this article.

Look back on the week that was with hand-picked articles from Australia and around the world. Sign up to the Forbes Australia newsletter here or become a member here.